In Toronto at the 2015 Pride Parade, Tom Mulcair laid it on the line: "We have four more months of really hard work ahead of us, but watch us go. They said in 2011 we'd never break through in Quebec. They said this year that we'd never form a government in Alberta.”

“On October 19th we plan to form a government in Ottawa."

Mulcair wore a rainbow-coloured, tie-dyed T-shirt. Nearby, Liberal leader Justin Trudeau also worked the crowd. Prime Minister Stephen Harper was nowhere to be seen.

The federal NDP leader tossed beach balls out and posed for selfies with parade participants to cheers and applause.

It was a classic Mulcair moment, one of many small public appearances that have boosted support for the NDP leader and led to the larger "Mulcair Moment" (coined by pollster Angus Reid in mid-June when Mulcair trounced his federal opponents in the polls).

This time last year, Mulcair's NDP was solidly in third place, clearly overshadowed by the Liberals. Now, Tom Mulcair has "all-of-a-sudden become the Dos Equis guy," Scott Reid writes in a recent Ottawa Citizen op-ed. The op-ed was titled: "In the midst of the NDP phenomenon, only the stupid are not terrified."

A June 2015 poll by EKOS showed Mulcair's job approval ratings at 60 per cent, compared to Justin Trudeau at 46 per cent and Stephen Harper at 32 per cent.

In the polls and on the streets, it seems Mulcair’s time has arrived. The lawyer and former provincial Liberal cabinet minister has broadened his appeal outside of his home province of Quebec.

Upcoming televised debates promise to boost his fortunes further, as he’ll have a chance to showcase the incisive, prosecutorial style he's become known for in the House of Commons.

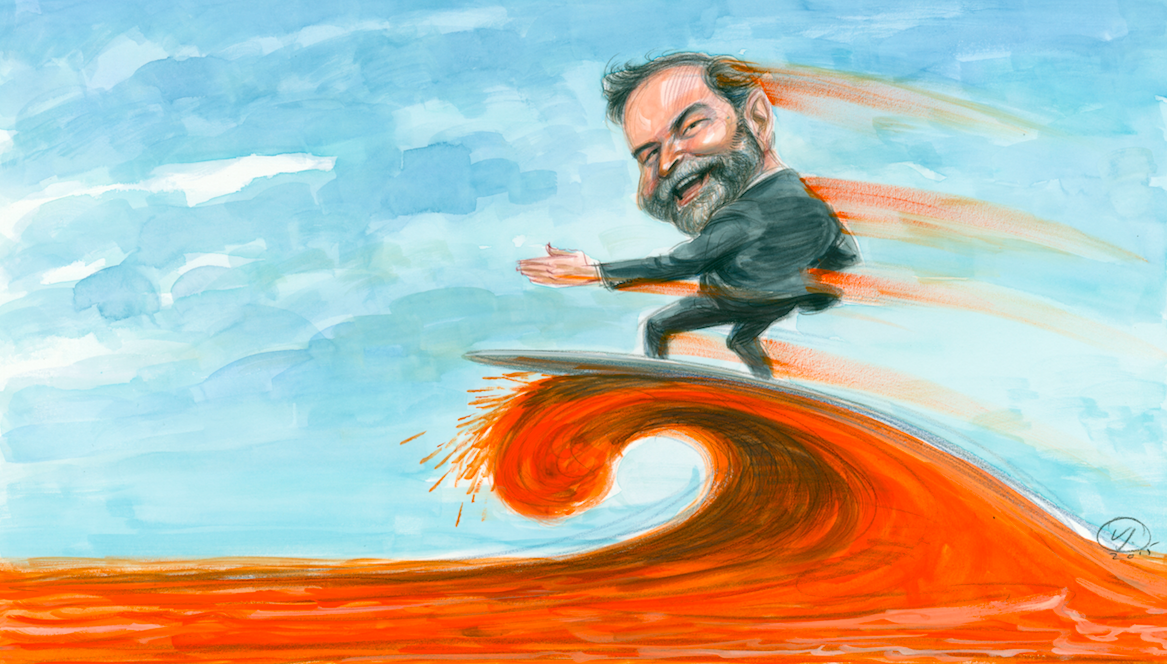

Mulcair wants to turn the Orange Wave that swept the NDP into the Official Opposition in 2011 into an Orange Crush this election— and those who know him say the veteran politician has prepared for this his entire life.

“I don’t think there was a day in his life when he didn’t want to go into politics,” Montreal businessman Geoffrey Chambers says of Mulcair. A former director of Alliance Quebec when Mulcair worked there as the director of legal affairs, Chambers has known Mulcair since the 1980s.

“He might not have known it until he was 14 or 15,” Chambers says, “but I think it runs very deep in him.”

Thirty years in politics, with help from Catherine

Born in 1954 at the Ottawa Civic Hospital to Irish-and-French-Canadian parents, Mulcair was the second-oldest of 10 children in a middle-class family living in Hull, Quebec. His father worked as an insurance executive before becoming an insurance broker. His mother taught school. Growing up as one of the oldest kids in a large household conferred responsibility on Mulcair at a young age and he helped look after the younger children.

Mulcair harkened back to his childhood in a recent speech, saying his beliefs and values stemmed from his upbringing. “We worked hard, played by the rules and lived within our means,” he told the crowd at the Economic Club of Canada in June 2015. “We learned the importance of looking out for one another, sticking together during good times and bad. These are the values that guided me throughout my 35 years of public life and my time as a cabinet minister in the Government of Quebec.”

Early on, Mulcair settled on law as a profession, graduating with degrees in civil law and common law from McGill University, where he was also president of the McGill Law Students’ Association.

During his university years he married Catherine Pinhas, whom he met while she was visiting Quebec from her native France. Pinhas immigrated to Canada soon after and the couple married in 1976 when they were both 21.

According to a 2012 article in the Toronto Star, Pinhas was the person Mulcair had "turned to first for nearly four decades."

"Every step in my political career, we have done everything together," Mulcair told the Star.

While Mulcair was bilingual, he wasn’t entirely fluent, according to the 2012 profile John Geddes wrote in Maclean’s. This was a problem, because his junior post in the Quebec civil service required him to draft legal documents and speak with colleagues in French.

Pinhas, who grew up in Paris and is a psychologist in Montreal, tutored Mulcair in the language, which he told Geddes represented “a huge turning point in his life.”

It was around this time too, Chambers says, that Mulcair grew his beard.

“He was a very good student and serious about making progress quickly in his career,” Chambers recalls.

“He went into it early and he made a success of it. I think that explains the beard. He decided very early on that he was tired of people saying, 'Hey kid,' because he didn’t look old enough to be doing what he was doing, so he grew a beard and never got over it.”

The Quebec years

By 1983, Mulcair arrived at the Alliance Quebec, a lobby for English-speaking Quebecers following the election of the Parti Quebecois in 1981.

As director of legal affairs, Mulcair led the charge against Bill 101, gaining a number of amendments to the Charter of the French Language.

“Whenever you hear hard-line separatists complaining that Bill 101 had a ton of holes driven through it, they’re talking about us,” says Eric Maldoff, the founding chair and president of Alliance Quebec and a former advisor to Jean Chretien.

According to Maldoff, Muclair’s work with Alliance Quebec and the language laws made him sensitive to English-speaking cultural issues across the country and didn’t just limit and confine his experience to Quebec. While Mulcair took on an important piece of work, leading the translation of Manitoba’s laws into both official languages after a Supreme Court of Canada ruling in 1985, he was far from done with Quebec.

In the 1994 provincial election, he won the Chomedey riding in the City of Laval, gaining a seat as Liberal member. John Parisella, head coordinator of the Liberal Party election in Quebec, wooed Mulcair to the party. Mulcair’s depth as an individual and his legal background, which helped him quickly absorb issues, made Mulcair appealing to Parisella.

Because Mulcair was now fluently bilingual, Parisella – a former chief of staff to Robert Bourassa, the 22nd Premier of Quebec – decided he could parachute Mulcair into a predominantly French riding. He had other people who could represent the English-speaking community.

“His mastery of the French language didn’t put him as an Anglo candidate even though he had an Irish name," Parisella says. "I felt that it gave him the chance to be part of the wider debate of the day."

Mulcair was re-elected in 1998 and 2003. With the Liberals under Jean Charest defeating the Parti Quebecois in the latter election, Mulcair became Minister of Sustainable Development, Environment and Parks. It was during this period that he drafted a bill for a sustainable development act that included an amendment to the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms. The bill enshrined the right to live in a healthy environment and call for a respect for biodiversity. The bill passed in 2006, becoming one of Mulcair’s proudest achievements.

But things were about to become bumpy for Mulcair. He accused Yves Duhaime, a lawyer and former Parti Quebecois of influence peddling, only to have Duhaime threaten defamation.

Mulcair snapped back, “I’m looking forward to seeing you in prison.”

The comments cost Mulcair $95,000, after the Quebec Superior Court ruled in favour of Duhaime.

In 2006 Mulcair opposed a proposed condominium development in the mountain and ski resort of Mont-Orford National Park. During a government shuffle, Charest offered Mulcair the lesser cabinet post of government services – many speculated because of Mulcair’s opposition to the project — but Mulcair flatly refused it. He left the cabinet and in 2007 announced he would run for the federal NDP in the next election.

Before committing to the NDP, Mulcair entertained offers from all the parties, with the exception of the Bloc. Mulcair was even in talks to be a senior advisor to Prime Minister Harper in 2007 before talks broke down, according to a recent Maclean's article. The Harper government also "floated" the enticement of a judicial appointment, according to journalist Charlotte Gray in a 2013 Walrus profile.

“Mr. Mulcair, he’s a fighter”

Where Harper failed, Jack Layton succeeded.

Over a six-month period the charismatic leader of the Federal NDP persuaded Mulcair to run in Quebec, a province without a single NDP seat. They targeted Montreal’s Outremont riding, which Mulcair easily captured during a by-election with 48 per cent of the vote.

“Tom's greatest advantage is that he's the real deal: intelligent, highly capable, empathetic," says Michael Byers, a Canada Research Chair in Global Politics and International Law at the University of British Columbia. "What you see is what you get, no spin required. Canadians will support him in ever greater numbers, as they come to realize that.” But Byers, a former NDP candidate for the riding of Vancouver Centre, says running in Outremont, a long-time Liberal seat, was not an easy way to go about getting elected. “From a political perspective he really laid it on the line in Outremont. If he had failed, that would have been very damaging to his political career, so he did take a risk."

As Layton’s lieutenant in Quebec, Mulcair went to work changing the NDP’s image in the province. One of the first changes was ensuring translations of party material were properly looked after. Up until then, French translations were poor, late or simply didn’t get done. Mulcair told Layton early on that if the NDP wanted to be taken seriously in Quebec, then you couldn’t look like you didn’t take Quebec seriously.

Mulcair instituted a policy of having everything translated properly and to a high standard. The process was expensive and sparked cultural pushback (presumably from wings of the NDP outside of Quebec), but Layton stood firm. He told the party they’d recruited Mulcair to change the culture and that they would support him.

In October 2008, Mulcair was elected to Outremont in the general election and then re-elected again in 2011. That was the election in which the NDP surged to capture 59 seats in the province and federally formed the official opposition. The giant leap in seats became known as the Orange Wave and along with Layton, Mulcair received credit for the cresting popularity of the party.

Maldoff says the large gain in Quebec is often attributed to the “Layton effect,” but he points out that Mulcair was on the ground with all the first-time candidates, "holding their hands and helping them through the campaign."

“I think it made a huge difference,” Maldoff says. “He was known and he knew Quebec. He was there with his team and earned their loyalty, kept that team together and kept them moving forward, the ultimate measure of a team player. If a leader can’t keep people with him, he’s not leading anyone.”

Still, Mulcair often came under criticism for not being a team player. Gray reported in her Walrus article that when Mulcair first arrived in Ottawa, his colleagues were less than keen on his “abrasive” style, which included “tantrums in and boycotts of caucus” and “explosive, spittle-specked rages.” According to Gray, “Layton tolerated the fireworks because he knew Mulcair was too valuable to lose.”

Earlier, a former Charest staffer told Gray that he wasn’t “a team player; he’s a Mulcair player.”

Similarly, in his Maclean’s profile on Mulcair, Geddes noted that his acid judgments in his early days rankled some NDPers who had been toiling for the cause long before he joined, and that he had bickered occasionally with veteran NDP MPs.

All of this led, in Geddes’ words, to “much later, during the leadership campaign, stored-up resentment over Mulcair’s penchant for finding fault emerged in the form of persistent complaints within the party apparatus that he was hard to work with.”

Today, Mulcair’s supporters shrug off such reports. Maldoff says, “He’s very smart. He’s very focused. He’s very determined. He’s a very able man. Is Tom capable of pushing? Is Tom capable of making a decision and being determined? Absolutely. And if you’re going to be in a leadership position, there are times to do stuff. Tom can be tough, no doubt about that. But anybody who thinks politics is a soft man’s game doesn’t understand it.”

Guy Lachapelle, a professor of political science at Montreal’s Concordia University and secretary-general of the International Political Science Association, says Mulcair is a “good politician” who previously had difficulty working as a team player. Lachapelle believes that when Mulcair became the NDP’s leader he learned to change his leadership style and unite the party, something which Chappelle calls one of Mulcair’s successes.

“Mr. Mulcair, he’s a fighter,” Lachapelle says.

Byers describes a man of conviction and passion who cares about social justice, the environment and people, and who possesses a strong will. “So, yes, absolutely, if you look back in his political history you see moments of passion. You also see evidence, as with the NDP leadership campaign, of an extraordinary ability to exercise self-control and to behave in a completely rational manner.

“What people want is someone who is both passionate and controlled at the same time. We don’t want our leaders to be dry and unemotional. Part of Stephen Harper’s problem is that he doesn’t show empathy and it’s a huge liability for him. Canadians want leaders who care,” Byers says.

“When Tom takes off his tie, and loosens up, he’s an incredibly gregarious, charismatic fellow. But when he’s got a job to do, he’s relentlessly pragmatic. He’s serious. He’s focused on getting the job done.”

In an interview with the National Observer in June, Gray said that Mulcair has overcome his previous reputation as “Angry Tom."

"He’s learned to smile," said Gray. "He’s learned to look cheerful.”

Mulcair's wife Catherine Pinhas has done few interviews, but in March she spoke with CTV. “There are things that happen that somebody has to be mad and say it and change it," she said, when asked about Mulcair's temper. She described her husband as “the kindest man you’ve ever met.”

A man Harper is afraid of

In August 2011, Layton died of cancer. Grieving over the death of his good friend and colleague, Mulcair wouldn’t even entertain the idea of running for the leadership at first. After a couple of weeks, Byers called Mulcair and told him that he hoped he would run. “The other potential candidates are good, but we need someone who Stephen Harper is afraid of,” Byers told the politician.

Mulcair entered the leadership race late, potentially damaging his chances to win. The final vote came down to him and Brian Topp. Currently the new chief of staff to Rachel Notley, Topp’s resume included working as Saskatchewan Premier Roy Romanow’s deputy chief of staff and as president of the federal NDP party. Topp’s impeccable party credentials didn’t stop Mulcair: on the fourth ballot he defeated Topp 57.2 per cent to 42.8 per cent.

At the time of the leadership convention, delegates faced a large split in approaches, according to Cristine de Clercy, an associate professor in the University of Western Ontairo’s political science department and co-director of that institution’s Leadership and Democracy Laboratory.

Mulcair promised to reinvent the party, strengthen it further in some key locations – notably Quebec – and move it into some new territory to attract key voters.

“Many people within the New Democrats were not totally sure that this was the right direction to go in,” de Clercy recalls. “We’ll see what the fall brings, but I don’t think now, several years on, one can say that his leadership was a failure, that these choices did not materialize real gain. He has, in sum, delivered on some of the promises he made to New Democrats in terms of shaping the party and trying to strengthen it in key areas.”

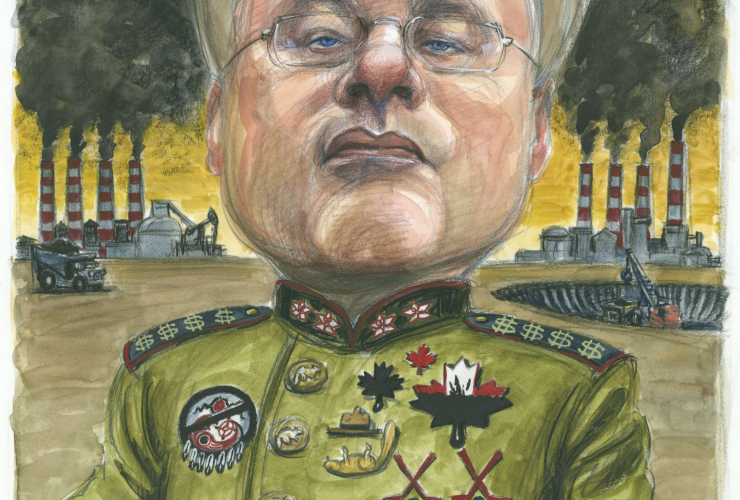

As leader of the opposition, Mulcair has fiercely challenged Harper and the Conservatives on everything from the proposed Keystone XL pipeline to the Senate scandals, calling for the abolition of the Senate after revelations over Mike Duffy’s expenses came to light. He tirelessly crusaded against Harper’s draconian Bill C-51, and, most recently, had the tax abolished on feminine hygiene products.

Mulcair has been very targeted with his criticism of the government in his opposition role, maintains Lydia Miljan, an associate professor of political science at the University of Windsor and director of that school’s Bachelor of Arts and Science program.

“When you compare Mulcair to Trudeau, though they tended to be criticizing the government from a similar perspective, Mulcair’s position was much more substantive than that of Trudeau’s, so I was curious why Trudeau was getting this great honeymoon in the polls and the press where Mulcair is doing all the heavy lifting,” Miljan says.

That’s changed as public opinion has finally caught up to the New Democrat leader; his consistently strong performance in the House has attracted peoples’ attention. “It’s only in recent months that he’s getting the positive attention that he rightly deserves over the last two years. In a lot of ways he had a difficult position,” Miljan explains. “He was eclipsed by the star power of Justin Trudeau, but now it looks like he’s coming into his own.”

Mulcair has every right to be confident, given the polls and the unexpected election of Rachel Notley and her NDP government in the traditional Conservative stronghold of Alberta earlier this year.

In its most recent poll in mid-June, Angus Reid showed the NDP leading with 36 per cent of the vote against the Conservative’s 33 per cent. The Liberals trailed with 23 per cent.

Furthermore, Mulcair’s approval rating soared to 54 per cent, up six points, well above Harper’s 37 per cent and Trudeau’s 43 per cent.

Just last week, poll aggregator ThreeHundredEight.com projected the NDP would capture 32.4 per cent of the vote and 127 seats in the House versus 28.9 per cent and 114 seats for the Tories.

Mulcair has already released some of his campaign platform in his speeches. This includes the use of an innovation tax credit to trigger research and development, the transfer of an additional cent from the gas tax to create a $1.5 billion infrastructure fund, the introduction of a new public transit strategy that would invest $1.3 billion annually in partnership with the municipalities, and a balanced budget.

Mulcair is also on the record saying that he would personally attend the UN convention on Climate Change in Paris in November, where he would show Canadian leadership and demonstrate that Canada would go from being a spoiler to a leader. He’s also committed to introducing a form of carbon pricing and eliminating subsidies to the fossil fuel industry.

But Byers says Mulcair’s most important environmental contribution would be to bring back rigorous, science-based environmental impact assessments.

“He regards it as one of the worst things the Harper government has done, to gut the environmental impact assessment process, to turn the National Energy Board into a rubber stamp for any project the Harper government wants to have happen,” Byers says.

A Canada rapidly turning orange

Has Notley’s Alberta win helped prepare the way for a potential NDP federal government? Parisella certainly believes so. He argues that if anyone didn’t consider the NDP was a mainstream party, that changed with the Alberta results. Notley’s win places the NDP in an entirely new light and has helped Mulcair’s fortune in the polls, maintains Parisella.

Traditionally the NDP acted as the conscience of the House of Commons, and were viewed as the third party. But now they run two Western provinces and act as the opposition in two more, and are a force in both Ontario and Quebec.

“Generally speaking,” Parisella says, “the reason why you’re seeing these close polls is the NDP is no longer seen as a third party. They’re seen as a player – and that’s what happens when you’ve been in opposition for nearly four years.”

When it comes to Mulcair, Parisella calls him the “most incisive, if not the most impressive leader in recent times.” He likens Mulcair to a prosecutor – no surprise, given Mulcair’s legal background – and points to his record of building support in Quebec and now leading a party that he refers to as “truly mainstream.”

In de Clercy’s view, Mulcair possesses the right skills to lead the party to success. “He’s the leader of the official opposition. He has managed to consolidate his party’s base in some new areas, particularly in Quebec. He’s very articulate. He’s feared in the House of Common’s question period. So he seems to have all the attributes of a future leader.”

Gray agrees that Mulcair has demonstrated his political strengths in the House and among his caucus. He’s been effective holding the prime minister responsible for whatever scandal is breaking and asking questions that can’t be dodged. At the same time, Mulcair has helped his new caucus, which contains many rookie politicians, understand how Ottawa works while keeping them in line.

“He’s admired within Ottawa for his performance in question period and for getting his caucus up to speed and that admiration translates to a press gallery that is taking him very seriously and, of course, that ripples across the country,” Gray says.

Even Mulcair’s detractors seem to have come around. Geddes wrote that at the time of the leadership convention, the party’s elder statesman, Ed Broadbent – the former leader of the NDP from 1975 to 1989, and a backer of Topp during the convention – dismissed Mulcair as “temperamentally too divisive to lead,” in Geddes’ words.

But in an interview with the National Observer, Broadbent said that Mulcair possesses "absolutely terrific skills" as a parliamentarian. “He is, I think, head and shoulders above anyone else in the House of Commons in being able to put accountable questioning to Mr. Harper. He zeros in on important issues.”

Broadbent said Mulcair’s ability in the House of Commons and his “overall intelligence” – not something to be under-estimated in a would-be prime minister – were well-known within Quebec, but have really only come to light in the rest of the country in the last nine months or so. “Canadians do see him as having the kinds of qualities that are necessary for a prime minister, the kind of intelligence,” Broadbent says.

That doesn’t mean the election will be an easy battle. De Clercy warns that Stephen Harper and his communications team have been adroit in past elections at crafting a message, consistently communicating it and securing the votes that they need to remain in government.

And Miljan says while polls favour the NDP in Quebec, they are lagging behind the Conservatives in Alberta. In Ontario, the Conservatives could potentially benefit again from vote splitting between the Liberals and the NDP, something that happened in the 2011 election as well.

Miljan believes the leadership debates and how the different leaders handle the rigors of the campaign trail will help determine the course of the election. The latter subjects the leaders to a grueling schedule during which they’re held under a microscope, where the media and social media amplify every misstep or mistake. “The focus is on those little things and campaigns have been derailed on the smallest of things,” Miljan says.

She points to the most recent Alberta election, where Jim Prentice was regarded as a star when he became leader of that province’s Conservative party. He was considered unbeatable, but a number of small mistakes and verbal gaffes, such as patronizing Rachel Notley in the debates — telling her, “I know that math is difficult” — led to his downfall.

“That kind of stuff resonates and it makes an impact and it changed everything,” Miljan says.

Considering Mulcair's chances and the campaign ahead, Byers calls Mulcair a “safe pair of hands." Mulcair offers Canada a high level of assurance he’s not going to “screw up."

"He’s not going to damage the economy, or take us into an unnecessary war. He’s going to provide good government." After ten years of Harper, says Byers, "I think people are reassured by that."

"I’ve never met anyone," continues Byers, "who’s more prepared to lead this country.”

Comments