Robert Brown has come a long way from his first development in Vancouver in 1998. Relatively new to the business back then, the Scottish émigré – who holds Canadian citizenship – built his first multi-residential project almost 98 per cent free of old growth wood.

Brown’s use of innovative green building strategies coincided with a big dip in the real estate market, resulting in a loss on his first project. “My wife calls it my $80,000 first degree, my MBA or whatever,” Brown laughs.

The idealism to construct without old growth wood, a radical idea at the time, came out of his experience hanging out in Tofino, British Columba, where the Clayoquot blockades were taking place at the time he was there. Brown met Nicole Rycroft, the founder of Canopy, an environmental not-for-profit, and she convinced him to build without the old growth wood.

Today, that same kind of idealism drives Brown’s newest venture, Catalyst Community Development, a non-profit housing company that develops existing real estate for social change. Catalyst works with other non-profits that own real estate and helps turn them into projects that will benefit the community.

Catalyst is one of a number of non-profit housing companies across Canada that is looking for solutions to the country’s affordable housing crunch. The way forward for them is finding new ways of financing projects at a time when public funding is shrinking.

Brown’s celebrating Catalyst’s second anniversary with two new projects. One is the construction of 49 below-market rate rental homes close to Victoria’s downtown. Consisting of two, three-storey buildings, Dockside Green will be built to LEED platinum standards. The units will range from 250-square foot studios to 1130-square foot four bedroom townhouses.

The second project consists of the redevelopment of the Oakridge Lutheran Church adjacent to Vancouver’s Oakridge Mall. Catalyst and the church will jointly develop, own and operate the new mixed-use building. The finished project will hold retail, while the second-floor will contain space for the church and community groups. Four floors of affordable housing will top the building.

At a time when many non-profit housing agencies struggle to find financing for their projects, Catalyst is thriving. Brown credits their idea to leverage what he refers to as social equity investors. Catalyst brings real estate development expertise and cash equity and then raises further equity from individuals and foundations that are interested in investing and getting back a fair return.

The return investors receive is below what they could make on the open market, but they want to support the projects. “I think there’s big, big changes happening with the decrease in public contributions,” Brown says.

“We’re having to look at more entrepreneurial solutions and so our model of tapping into private equity at more reasonable rates of return is a more entrepreneurial model.”

Catalyst builds affordable rental housing for people who earn between $25,000 and $65,000 annually. The company focuses on rental housing because it believes “there’s a huge squeeze on rental housing.” As well, the housing that is available is priced significantly above what people in that income bracket can afford.

“A lot of renters are paying over 50 per cent of their income on their housing,” notes Brown.

That income gap is not unique to Vancouver. Affordable housing is a problem across Canada. Last May, in the first 20-year survey of public housing trends in North America, Europe and Asia, researchers found a decline in Canada’s investment in public housing.

Using data from governments, housing and non-profit agencies, the researchers at the University of British Columbia’s School of Community and Regional Planning found the number of public housing units in Canada dropped by five per cent between 1990 and 2011.

Lead researcher Penny Gurstein called the consequences of the drop disastrous. “Housing prices relative to income have sharply increased in urban areas, affecting access to adequate housing for low-to-moderate-income people,” Gurstein said at the time of the report’s release. “The number of homeless – and people at risk of becoming homeless – has markedly increased in the last two decades.”

At the same time, federal subsidies for housing co-ops and non-profit housing is scheduled to end soon. More than 21,000 low-income households Canada-wide live in mixed-income housing co-ops and even more live in non-profit housing.

During the election campaign, the Liberal Party in its platform noted that one in four Canadian households pays more than it can afford for housing and one in eight cannot find affordable housing that is safe, suitable and well-maintained.

Justin Trudeau campaigned partly on affordable housing for the country, promising to build more, new housing units and refurbish old ones; and to remove the GST on new capital investments in affordable rental housing, which would provide $125 million annually in tax incentives to grow and renovate the country’s supply of rental housing, among other things.

“It’s a massive, massive issue and there’s a massive opportunity.” says Brown.

Building non-profit housing is a tricky venture

Truer words couldn’t be spoken. Look to Toronto for proof. There, Mike Labbe, the founder and president of Options for Homes, is building at a frantic pace – and he even he can’t keep up with the demand.

Since 1994, Options for Homes has developed 6,500 units in Toronto, Montreal, Waterloo and Kingston. According to Labbe, back in 2002, Toronto needed some 7,000 units per year. “Well, we’ve never produced more than 1,000, so there’s this built-up demand for affordable housing.”

Options for Homes offers a loan in the form of a second mortgage to low-income homebuyers, which they don’t pay on until they sell or rent their suite. The loan enables many individuals to purchase a place that otherwise would be out of their reach.

At the same time, the company’s partner, Home Ownership Alternatives (HOA) provides capital to help with land acquisition and pre-construction costs; and provides equity and guarantees construction support. By stripping out a lot of the margin, Options for Homes is often able to offer homes for as much as $100,000 below market value.

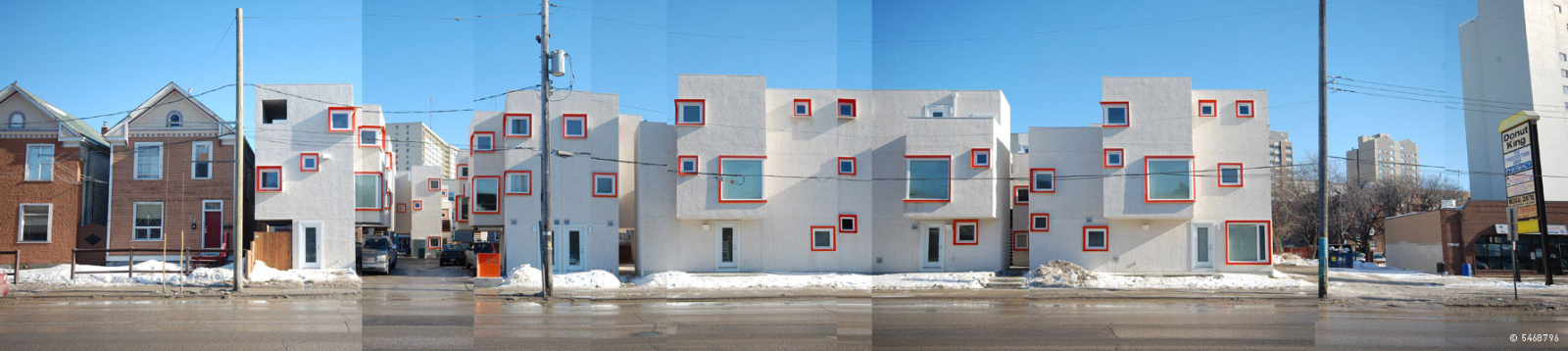

Building non-profit housing is a tricky venture. Just ask Colin Neufeld, a partner in Winnipeg-based 5468796 Architecture. The firm built a 25-unit micro-village known as Centre Village on a parcel of land originally meant to hold six houses. The development of six, three-storey blocks was shortlisted for three awards.

As its name implies, Centre Village is more than just a collection of units; it’s a community. The development is designed around a series of courtyards to encourage neighborly interactions and each unit has its own front door.

“From our perspective, non-profits have a higher interest in the daily life of people living there – not just in giving them a bed to sleep in, but a community to live in,” Neufeld says.

Neufeld notes they pushed hard to have the individual front doors and the three-storey walk-up style rather than one block to create a more livable situation. “They’re coming from a housing block,” he says of Centre Village’s inhabitants. “They don’t need to get put back into a housing block. It’s not transitional housing.”

Nor is Centre Village the only non-profit project Neufeld and his partners have done. Welcome Place is a shelter and transitional service provider for Manitoba’s new refugees, with offices on the lower floors and three levels of residential suites above.

In their architect’s statement, 5468796 speaks about the mix of private accommodation and open public spaces within the building, and how once the occupants became familiar with their surroundings they will gradually transition from one to the other, easing into the surrounding community.

“This act is a first step towards their lives as Canadians.”

Neufeld says as an office, they’ve all been touched by non-profit housing. One of the founding partners came from the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s as a refugee, and Neufeld says he has a personal connection through his church.

“For me personally, it’s a cause that I think we need to be addressing aggressively and insert ourselves into. Different economic classes deserve to live just as well as anybody.”

Originally, a group from Knox United Church organized Centre Village as a housing co-op. They purchased and assembled the land and approached 5468796 Architecture to design it. But along the way the co-op wasn’t able to generate the funds required to own the project and it was sold to Manitoba Housing, who saw it through to completion.

“You have to have capital to pull off large developments, even medium size developments,” Neufeld says, “and not for profits are out there for the social good. They don’t have the capital backing.”

Neufeld knows of a number of church groups which are interested in creating some non-profit housing, but he says they have a difficult time getting the projects off the ground. They have the clientele for the housing and they could run it, but the banks are reluctant to finance the projects.

“They’re going to finance it at 30 or 40 per cent equity in, so you have to generate that 30 or 40 per cent equity and that’s a big number for non-profits to find,” Neufeld says.

That’s a typical scenario facing a lot of agencies that would like to develop housing, but can’t because of the financing.

There is an opportunity to build the non-profit sector as a driver of the economy

Back in Vancouver, Brown opines that some of the existing non-profit housing agencies are in the process of becoming more entrepreneurial. He says they’re looking at new solutions because the old ones no longer work.

“They’re primarily based on significant public dollar contribution. It’s just not happening. So they’re transitioning in some way and it’s taking a number of different forms, but they know that the model has to shift.”

Brown sees government moving its support to individuals on welfare and homeless shelters. He describes that as a level at which no form of market sector or non-profit can cater to without public support.

That would move the more entrepreneurial non-profit activities into the middle, where incomes range a bit higher, the area in which Catalyst and others are already working. Says Brown: “I think there’s an exciting opportunity to build the non-profit sector as the driver of the economy and to have non-profits more fully engaged in driving those solutions.”

It’s a great thought, one that just might go a long way toward solving the housing problem.

Comments