After seven years of acrimonious court battles, profligate spending and hardball political lobbying, the Keystone XL pipeline is dead. U.S. President Barack Obama rejected the proposal, as most suspected he would.

"Several years ago, the State Department began a review process for the proposed construction of a pipeline that would carry Canadian crude oil through our heartland to ports in the Gulf of Mexico and out into the world market," said Obama in a press conference on Friday November 6.

"This morning, Secretary Kerry informed me that after extensive public outreach and consultation with other cabinet agencies, the State Department has decided that the Keystone XL pipeline would not serve the national interests of the United States. I agree with that decision."

Environmental organizations cheered the decision, which was viewed as an important and meaningful decision ahead of the Paris climate talks.

"The Keystone rejection sets a new and important precedent in the run up to the Paris climate talks that we hope Prime Minister Trudeau will take to heart, project approvals must take climate impacts into consideration so that we are building the future instead of stuck in the past. Why? Because its 2015," said prominent Canadian environmentalist Tzeporah Berman.

The collapse of Keystone XL represents a spectacular failure for Canada's former prime minister Stephen Harper, who lobbied hard for the pipeline in recent years. In an interview with Bloomberg Television, he had openly criticized the Obama administration, commenting: “I think there’s very peculiar politics of this particular administration.”

Harper's statement drew angry reactions from U.S. opponents of the pipeline.

Jane Kleeb represents Bold Nebraska, a citizen activist group that has been waging a court battle against the pipeline’s use of eminent domain to seize lands from farmers and ranchers.

Talking on the phone from Hastings, Nebraska, Kleeb said she believes relations between the U.S. and Canada were damaged by Harper’s heavy-handed lobbying.

The effort included a multi-million campaign to target legislators, academics and others with Keystone XL advocacy, as well as a $24 million, taxpayer-funded ad campaign to get Americans on board with the project.

“President Obama would never spend $24 million of taxpayer's money up in Canada to get a project approved – and that’s what Harper has done,” Kleeb said.

“There’s this tremendous distrust... where is the line between oil companies, the oil industry and the government up in Canada? That line has been too blurred from our perspective.”

Harper wasn’t the only one spending money to make sure the pipeline went through. The billionaire Koch brothers shelled out $53 million to think tanks and other groups supporting Keystone XL, according to a May 2015 report from the International Forum on Globalization (IFG), a "North-South" research institute that studies the impacts of global commerce.

The IFG says that the money bought the brothers nearly 1,000 pro-Keystone XL reports or statements issued from think tanks and support groups.

The Kochs also have spent $76-million on Congressional candidates who support the tar sands and the pipeline, and outspent all other oil companies to block U.S. climate action through lobbying, the report details.

This outlay of capital to influence policy should perhaps not be surprising, as the Kochs are the largest foreign lease-holders in the tar sands. In a recently-released map of tar-sands holdings, the IFG contends the brothers own close to two million acres of Alberta's tar sands — equivalent to over 8000 square km, an area larger than the state of Delaware.

The IFG notes that in the Canadian tar sands the Kochs have "almost as many carbon assets at stake [as] Exxon, Chevron, and Conoco’s combined."

Yet despite the massive spending and aggressive lobbying, Keystone XL is finished.

A historic victory for North America's climate movement

“It’s historic,” said Adam Scott, the climate and energy program manager for the Toronto-based group, Environmental Defence.

“It’s a massive victory for the climate movement in North America, who have been growing and building in strength over the last six years, and this project is very symbolic of the strength of the climate movement.”

Without the pipeline, it is almost certain that planned expansion of the tar sands will have to be scaled back.

Certainly, for climate change activists, the tar sands – and Keystone – have been a major hurdle when it comes to focusing on such things as energy solutions to climate change. Scott said that discussion between the U.S. and Canada stalled out because the “Canadian government has been so focused on this one dirty industry and its export pipelines.”

Scott noted the federal government has stressed the energy industry at the expense of diversification into other areas. “Canada has a lot more to offer than just tar sands," he said.

“We think the strategy that Canada has been pursuing of just this one industry has been proven already to be a failure and rejection of Keystone would be the final proof of that.”

From Kleeb’s perspective, it Obama rejects Keystone, it will be the first time in recent history that a president has turned down a pipeline based on climate change and concerns over property rights and water.

“It will be a significant kind of indication, a flag in the ground, if you will. There’s a shift that we the people actually matter more than Big Oil, which is a major shift for American politics.”

The perfect storm

The failure of Keystone XL is also a troubling sign for the planned expansion of Alberta's oil sands, which Harper long hoped would become the backbone of Canada's status as an "emerging energy superpower"— a term he used in an international speech soon after his 2006 election.

“By the time he was sworn in as prime minister in February 2006, Harper saw the oil sands as his nation’s route to riches and stature,” Bloomberg News reported in 2014.

TransCanada, the Calgary-based infrastructure company, had the key. Keystone XL wasn’t an accidental name— it was supposed to unlock Canada's "superpower" potential.

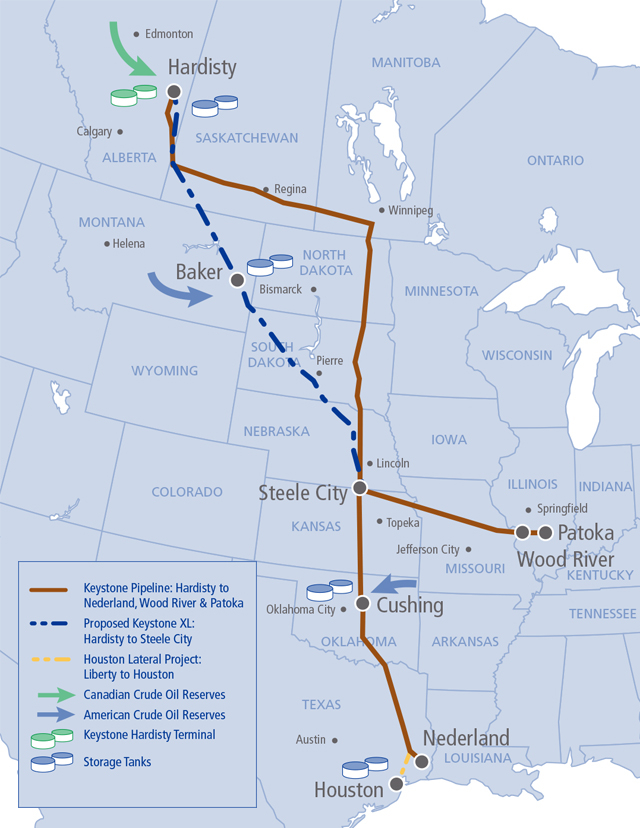

First proposed in 2008, the 36-inch pipeline would carry 830,000 barrels of oil a day from the oil depot town of Hardisty in south-eastern Alberta, through the American states of the Dakotas and Nebraska to refineries in the Midwest and Gulf Coast.

The pipeline remained under the radar until 2011, when it ran into a perfect storm— a well-organized movement of climate change activists and the wrath of farmers and ranchers in Nebraska.

Author and activist Bill McKibben helped organize a two-week civil disobedience campaign outside the White House to protest what he called “the fuse to the largest carbon bomb on the continent."

The protest was the largest civil disobedience protest of its kind since the 1960s. It resulted in the arrests of over 1,000 people, including prominent Canadian author Naomi Klein.

McKibben’s interest in Keystone, and ultimately the White House protests, were sparked by the writings of former NASA climate scientist Jim Hansen. In a 2011 paper, and later in a New York Times op-ed, Hansen wrote that the tar sands were so massive that burning them along with other carbon reserves would mean “game over for the climate.”

McKibben read Hansen’s critiques, and he began to pay attention to the nascent Keystone XL pipeline. Realizing that the megaproject would require a presidential permit, he worked to organize pressure to Obama through protests and organized opposition.

Furor over the pipeline caused the proposal to falter

At the same time that McKibben was tuning in to Keystone, salt-of-the-earth Nebraskans were expressing outrage at the proposal of a heavy crude oil pipeline that would run across the Sandhills region – a National Natural Landmark in the U.S. – and over the Ogallala Aquifer. The latter is a critical source of groundwater for drinking and irrigation in the state.

The number of jobs the project would create quickly came into question. The Cornell University Global Labor Institute released a study dismissing TransCanada’s claims that the pipeline would kick-start tens of thousands, even hundreds of thousands, of jobs.

Instead, the study argued Keystone XL would create 2,500 to 4,650 jobs and the bulk of those would be temporary and non-local. The study bluntly concluded that the employment potential from the pipeline was “little to none,” and the “decision should be based on other factors.”

Suddenly, Keystone XL didn’t look like such a sure thing anymore. In October 2011, Nebraska's then-governor Dave Heineman called the state legislature into a special session to determine if siting legislation could be crafted and passed for pipeline routing in Nebraska.

By November, TransCanada announced that it would work with the state to identify a potential pipeline route around the Sandhills region.

That December, new legislation came into effect, requiring the U.S. Secretary of State to issue a permit for the project within 60 days unless the president determined the pipeline was not in the public interest.

In January 2012, the U.S. Department of State said – with Obama’s consent – that it would deny the Keystone XL permit.

The decision was made on the basis that it was believed the 60-day period wasn’t enough time to gather the information necessary to make an informed decision as to whether or not the pipeline was in the national interest.

Obama’s permit denial shocked and then angered Harper. “Harper couldn’t let go,” Bloomberg Business reported. “Even his inner circle was taken aback by the depth of his criticism for Obama and the frankness with which he expressed it.”

Keystone XL's final act

The maneuvering continued over the next year. TransCanada announced that it would proceed with the development of the southern pipeline as a separate proposal and submitted a new presidential permit to the Department of State for alternate routes through Nebraska.

In 2013 the Environmental Protection Agency raised environmental objections to the environmental impact statement (EIS) and added that the EIS included insufficient information.

The next year a Federal Register Notice calling for members of the public to comment on the pipeline project drew more than 2.5 million comments over a 30-day period. The presidential permit itself required the project meet a number of factors, ranging from energy security and environmental to cultural and economic impacts.

No less than eight federal departments were involved in the review, including Defense, Justice, the Department of Homeland Security, Commerce, Energy and the Environmental Protection Agency.

In 2014, the Keystone XL bill failed to pass the Senate. That would prove only a temporary set-back as shortly after that vote an election allowed pro-pipeline Republicans to dominate the House of Representatives.

In early 2015, after years of political wrangling, the House passed the Keystone XL Pipeline Act by 266 to 153.

In late January, the bill made it through the Senate— but with five votes shy of preventing a Presidential veto, which Obama exercised in February.

In a final, desperate attempt to keep the project alive, TransCanada asked for a "pause" of the review in early November. The company was gambling that a stall in the project until after the U.S. presidential elections might allow time to bring in a Republican government favourable to the pipeline. The Obama administration flatly rejected the idea.

Can the pipeline project return if Obama kills it?

The biggest stumbling block remains the oil sands companies themselves. Swift said a credible scenario doesn’t exist where the U.S. and the international community can reduce global emissions to the amount the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change specifies while expanding production of some of the world’s most carbon-intensive oil reserves.

Now that Obama has killed the pipeline, is there any possibility for TransCanada to resurrect it under a new administration?

According to Kleeb, the next president can’t just resurrect Keystone XL because the permit will have been fully rejected. That means TransCanada will have to reapply with a new environmental impact assessment, new landowner easements and so forth.

“It would be a minimum two- to three-year process for TransCanada, assuming that they had a president that was friendly toward tar sands,” Kleeb said.

Swift said in recent months Obama has signaled his thinking about the pipeline and is even clearer on climate issues. “I think this project is really highlighting the fact that it’s going to be very difficult going forward to separate the question of tar sands expansion and the question of climate.”

In Toronto, Scott agrees. He said Keystone XL will just be the first of many projects in the future around which there will be difficult conversations. “We cannot keep building fossil fuel infrastructure that locks us in for decades of rising emissions in an era of a warming climate."

Comments