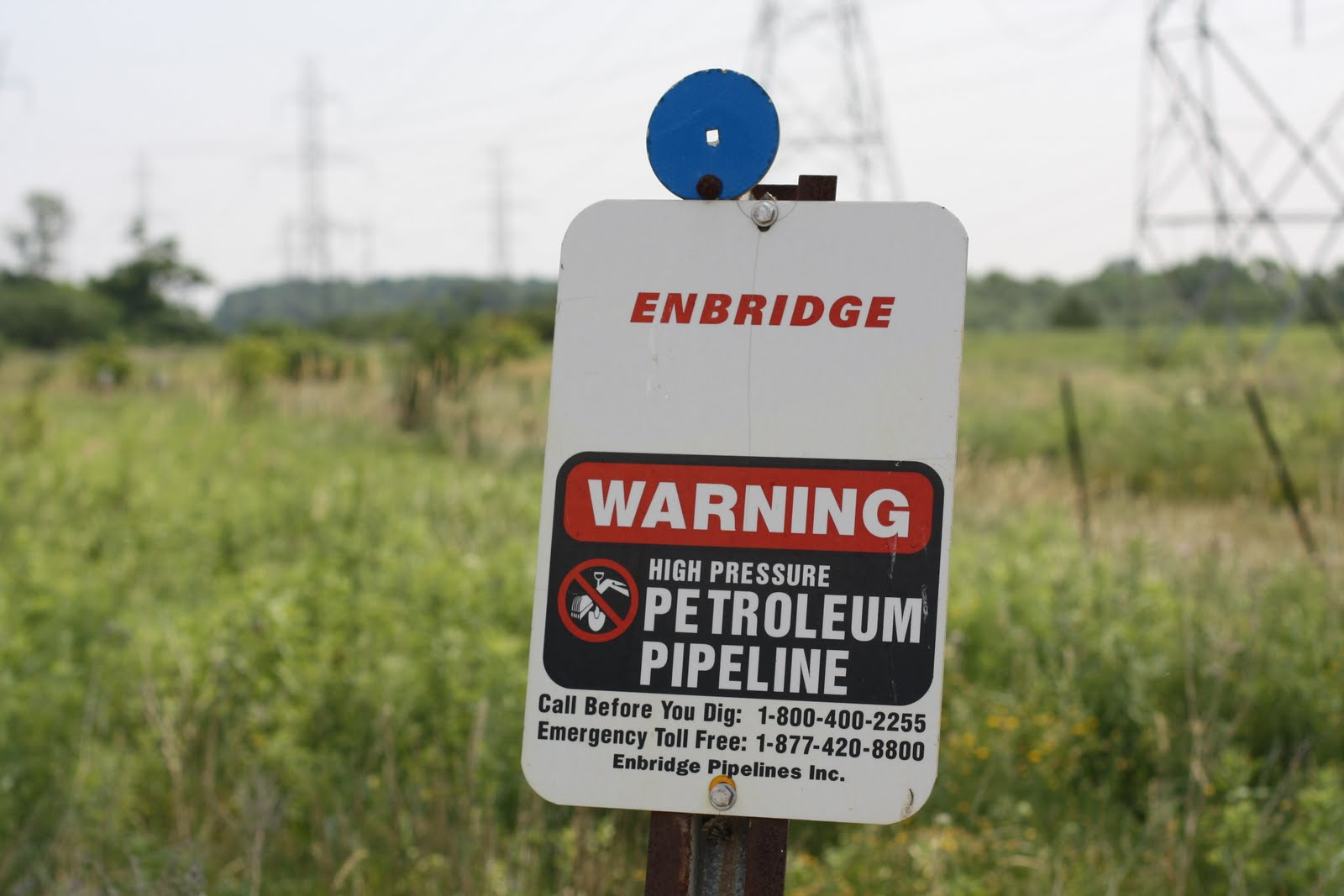

In its drive to expand pipeline capacity in the United States, Enbridge has consistently circumvented state regulations and exploited loopholes, according to a new report from a coalition of environmental agencies.

Titled Enbridge Over Troubled Water, the report shows how the energy company has been methodically putting together a massive system of pipelines piece-by-piece through the U.S. Great Lakes region.

Enbridge is trying to increase the amount of tar sands crude that flows through the pipeline system - collectively known as Enbridge GXL - to 1.1 million barrels per day - substantially more than what was proposed for the rejected Keystone XL Pipeline.

The report says that the Canadian company has consistently worked behind closed doors with regulators to avoid the type of public environmental review that killed Keystone XL.

The coalition of groups that worked on the report included the U.S. Sierra Club, 350.org, Bold Nebraska, and the National Wildlife Federation.

Among the revelations in the report is how Enbridge doubled the amount of tar sands crude coming across the border on its Alberta Clipper line. The report alleges that the company gained “backdoor approval” from the State Department to manipulate its border crossing in order to increase the amount of crude it moves through the U.S.

In 2014 the company proposed building a higher-capacity pipeline just a few feet away from the existing Alberta Clipper and which would cross the border on the same right-of-way. Oil from the Alberta Clipper would be diverted to the new pipeline just before the U.S. border and then re-diverted back to the Alberta Clipper after.

Enbridge positioned the construction of the new line as routine maintenance of an existing 1960s pipeline known as Line 3. That line was built before the U.S. National Environmental Policy Act was passed and, according to the report, never underwent an environmental review.

The “maintenance” allowed Enbridge to skirt the ongoing federal review process and expand the Alberta Clipper pipeline immediately without any public or agency involvement, the report contends. The State Department issued a letter saying changes to the operation of the pipeline outside of the border did not require authorization from the department.

A coalition of environmental and First Nations groups challenged the expansion in federal court in 2014, but a judge ruled that it did not have authority to decide on the matter.

In October 2015, eleven senators wrote to the State Department raising questions about why Enbridge’s pipelines were not being held to the same standard as Keystone.

The report also highlights how the company is planning to build a new line in a new corridor through Minnesota’s “pristine” lake country and then abandon Line 3, which is described as a “corroding pipeline” built in the late ‘60s.

The new line would add another 370,000 barrel per day capacity of tar sands crude across the border.

The company also wants to expand an existing pipeline through Wisconsin and build a new one next to it. The expansion would link pipelines in Minnesota to a web of pipelines in Illinois that would transport tar sands crude through a series of lines from Portland, Maine to Houston, Texas and further.

The report is also highly critical of Enbridge's environmental record, noting that the company was responsible for the largest inland pipeline disaster in the U.S., the July 2010 spill in Michigan’s Kalamazoo River.

It also pointed out that Enbridge’s pipelines have had more than 800 spills in the U.S. and Canada between 1999 and 2010, leaking 6.8 million gallons of oil.

Nor did the report have kind things to say about Alberta, calling the province “home to one of the most destructive industries on earth,” in reference to the tar sands.

The coalition that produced the report argue that like Keystone XL, the expansion of Enbridge GXL, fails the test of public interest.

“Enbridge’s GXL massive tar sands oil expansion plans need to be thoroughly and publicly scrutinized and rejected,” the report concludes.

Comments