As it stands, the Pacific NorthWest LNG project is lined up to become one of the worst carbon polluters in Canada.

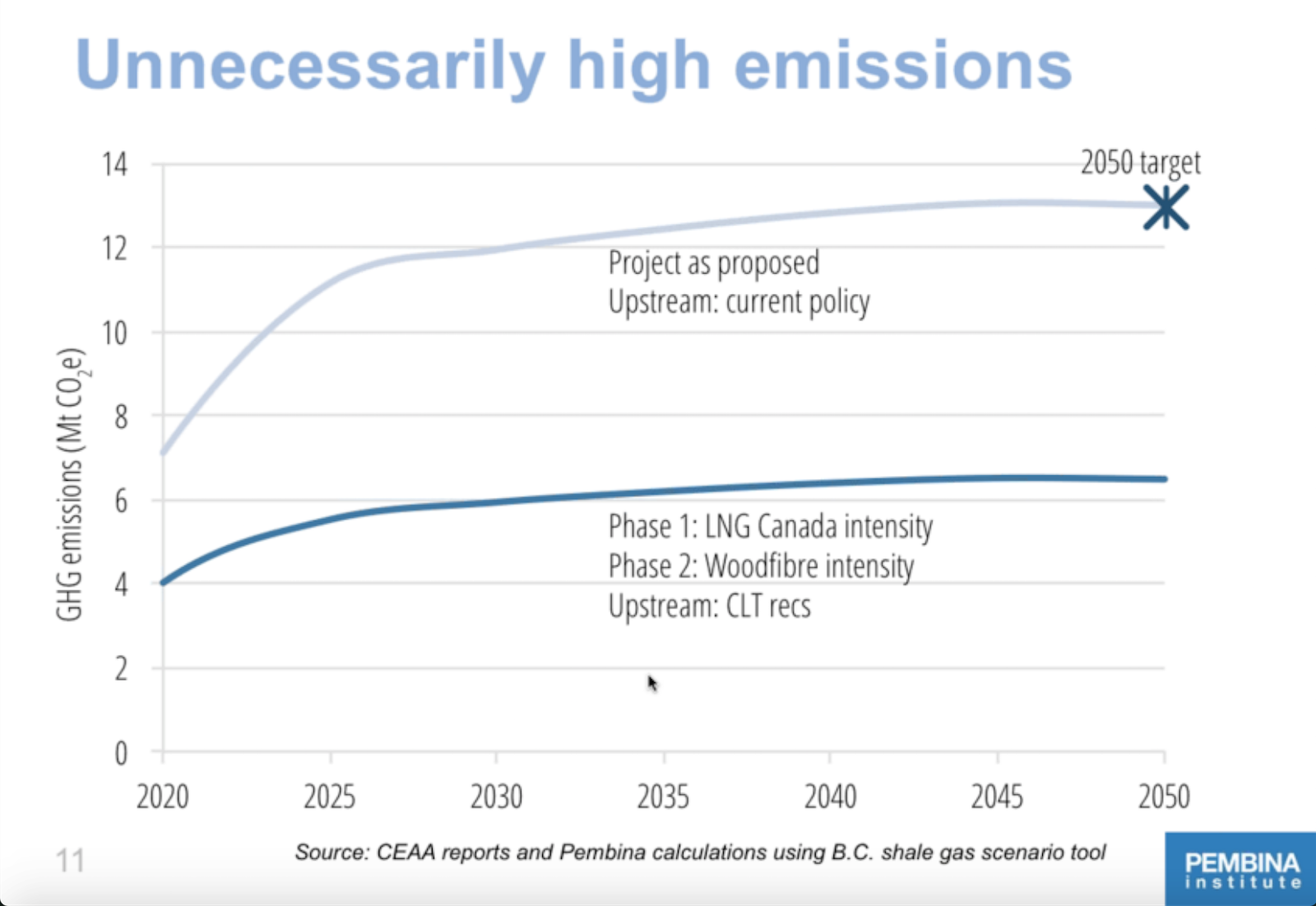

If constructed, it could account for up to 87 per cent of all emissions allowed under B.C.’s 2050 target according to the Pembina Institute, and make a mockery of climate commitments made by Canada in Paris and New York City.

But it doesn’t have to be that way, say experts at the energy and environment think tank — with a bit of tweaking, the Pacific NorthWest LNG project could come much closer to meeting provincial and national climate targets.

“You’ll still have a significant chunk of emissions from that project,” said Matt Horne, associate regional director for the Pembina Institute in B.C. “You’re not going to have zero emissions on an industrial project of that scale, but it can do 50 per cent better than what was initially proposed.”

Reducing LNG emissions

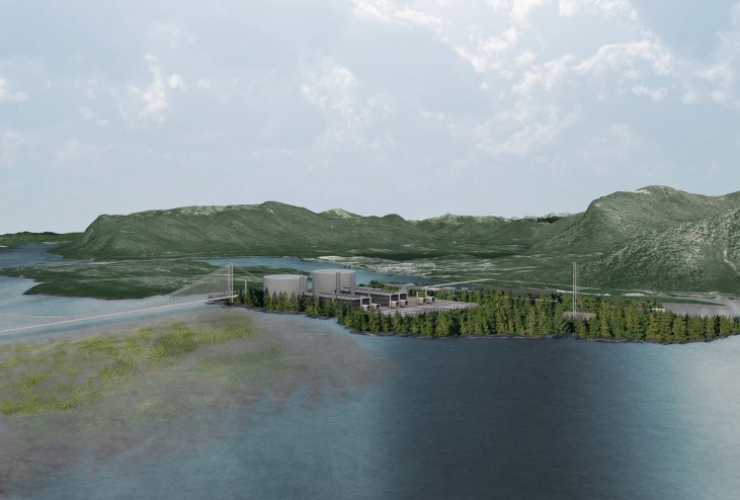

The $36-billion Pacific NorthWest LNG project is a hotly-debated natural gas liquefaction and export facility-and-pipeline combo proposed for the northwest coast of B.C. If approved, it is expected to generate up to 4,500 jobs during peak construction and $2.5 billion in annual tax revenue for all levels of government.

Aside from becoming a large carbon polluter however, environmentalists and First Nations are also believe the Petronas-led initiative will wipe out salmon in northeastern B.C., damage the ecosystem on the precious Flora Bank, harm harbour porpoises and plough through unceded Indigenous territory.

While the Pembina Institute’s suggestions won’t solve any of these problems, they could help the proponent cut down on its emissions significantly:

“The LNG terminal can be looking at more efficient drives for liquefaction, renewable energy for the auxiliary — which is something LNG Canada is doing — and electric drives,” Horne explained. “There is significant opportunity to reduce emissions from the project as proposed.”

On the upstream greenhouse gas emissions, he recommended carbon capture technology, taking advantage of recommended methane reduction strategies, and again, using electric power.

“One place where electric drives are being used is the Woodfibre LNG project in Squamish,” said Horne. “It probably couldn’t be in the near-term [for Pacific NorthWest LNG] because of transmission constraints, but definitely in the medium-term and a possibly for a phase two of the project.”

A path of climate leadership

The climate researcher said the federal government also has a role to play in reducing Pacific NorthWest LNG's footprint; it could give conditional approval of the project by issuing a set environmental standards around its emissions intensity.

It could also implement new federal climate policies that would apply to the entire oil and gas sector (including the methane regulations committed to by Prime Minister Trudeau and U.S. President Barack Obama), and push the B.C. government to adopt a set of November 2015 environmental recommendations from the provincial Climate Leadership Team.

"For Canada to be successful [with its climate targets], each of the provinces need to be successful," he explained. "There is a pathway to move forward that puts B.C. on a trajectory for declining emissions, but to date, the province has not adopted those recommendations."

Horne was part of the leadership team that put together the package for B.C., which included guidelines for LNG industry policy, and carbon tax improvements and offsets. If Pacific NorthWest LNG were built according to the team's recommendations, it would be forced to cut more than half of its emissions by using different technology and procedures.

When asked why Petronas and the project's other shareholders wouldn't simply adopt these measures voluntarily, he said the answer was "complicated."

"I think some of the challenges here are companies and proponents will take different outlooks on the future and how climate policy may evolve," he explained. "That’s one of the factors. It's interesting to look at LNG Canada and Pacific NorthWest LNG as sort of a good illustration that similar projects of similar sites and locations don't always come to the same conclusions."

Pacific NorthWest LNG is currently under review by the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (CEAA), which has asked the proponent for more information on the project's potential impacts to fish, marine mammals and human health. In its draft review of the project, it listed greenhouse gas emissions as a key area of public concern.

If the federal government approves it as is, said Horne, it would call into question the country's "seriousness" when it comes to climate commitments.

Comments