A bill to expand protections for journalists' sources would give desperately needed reassurance to Canadian reporters and whistleblowers, representatives of some of Canada's largest news outlets told a Senate committee on Wednesday.

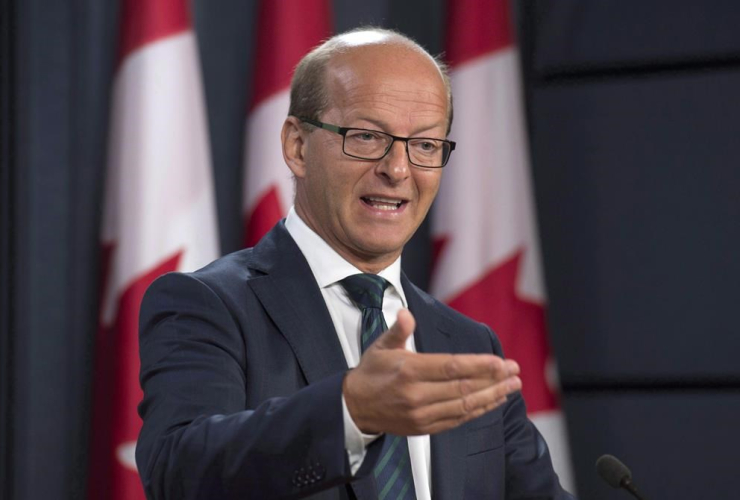

The testimony and the legislation, proposed by Conservative Sen. Claude Carignan, are a direct response to recent cases in which police have tapped the cell phones of journalists and monitored their communications to identify sources blowing the whistle on alleged inappropriate actions by people in positions of power.

“Confidential sources exist for good reason. For decades, the public interest of Canada has been served by those who come forward, often at great personal risk,” David Walmsley, editor of The Globe and Mail, said on Wednesday in testimony before a Senate committee studying the private member's bill, S-231.

Walmsley and other senior news officials told the committee that the recent cases show whistleblowers are under threat in Canada.

Editors from the CBC, Radio-Canada, Le Devoir, La Presse and the Toronto Star all spoke in favour of the Senate bill, which would expand protections for journalists' sources and make it more difficult for police to tap journalists' phone conversations, track their phones or seize documents and other evidence. The bill would also give journalists greater protections to refuse to give information that could identify a source.

In addition, only Superior Court judges would be allowed to authorize warrants or orders targeting journalists under Carignan's proposed bill. Currently, justices of the peace can also sign those orders in some cases.

Carignan tabled the bill in Nov. 2016, after reports that Montreal police had monitored the cell phones of two La Presse journalists, Patrick Lagacé and Vincent Larouche. Police said they were trying to use Lagacé's phone to track down a police officer they believed had leaked information to the media.

Montreal police chief Philippe Pichet said the monitoring was an "exceptional case," but Quebec provincial police later admitted they had also monitored at least six journalists, including Alain Gravel, former host of Radio-Canada's investigative program Enquête, whose phone was tapped for five years.

“As an industry, we are appalled with the recent revelations of what has gone on in Quebec,” Walmsley said.

Those revelations showed that journalists in Canada were living in “a new reality,” La Presse editor-in-chief Éric Trottier told the committee on Wednesday. “We thought this type of intrusion would never happen in a democracy like Canada,” Trottier said.

“It's crazy, in our period of time that we have seen police forces using their power to track journalists, and using journalists to find another person,” Carignan, the bill's author, said in an interview. “Liberty of the press is a pillar of democracy,” he said.

Toronto Star editor-in-chief Michael Cooke noted that the police investigations in Quebec were aimed not at major criminals but rather "were carried out with the sole purpose of identifying whistleblowers or even stopping simple internal leaks from the police force, and that's alarming."

Canada is one of just a few developed, democratic countries without shield laws to protect journalists, Cooke said. “It's a very small, tiny club, and we should not be a member," he said.

Currently, Canada has no laws to protect journalists who refuse to give up sources, and they can face steep financial fines, or in theory, jail.

That's the penalty Vice News journalist Ben Makuch could face in a case now before the Ontario Court of Appeal, in which the RCMP have demanded that he turn over logs of messages he exchanged with alleged terrorist Farah Shirdon.

With no shield law to protect journalists in Canada, each case involving a journalist's sources is decided on a case-by-case basis. That can take years. In one recent case, a Hamilton Spectator reporter was fined $31,600 for refusing to give up a source. The fine was reversed on appeal, four years later.

“Society as a whole is affected when the journalist-source relationship is undermined,” Carignan told the Senate committee on Wednesday.

That can have a chilling effect on public interest journalism, Walmsley said, describing the steps reporters must now take to protect their sources from police eyes: encrypting electronic communication, minimizing or avoiding phone conversations entirely and often meeting only in person. And even then, the paper's journalists can never absolutely guarantee that a source's identity will be protected, he said.

“Right now, sources are afraid,” La Presse editor Trottier said. “This bill will reassure a lot of people.”

Under the bill, which aims to amend the Criminal Code and the Canada Evidence Act, a journalist could be compelled to give information that could identify a source only if a judge was satisfied that there was no other way to get the information – and then only if a judge concluded that the public interest in the case's investigation outweighed the public interest in maintaining the integrity of the journalist-source relationship.

Similar rules would apply to police applying for a warrant to force journalists to hand over notes, recordings and photos or video, as well as to tap or track phones belonging to journalists.

Moving the responsibility for those orders to a higher level is especially important given media reports last year that revealed Montreal justices of the peace approved 98 per cent of all warrants requested by police, CBC editor-in-chief Jennifer McGuire told the committee.

She said that the media organizations testifying on Wednesday are recommending that the bill be amended to give lawyers representing media the chance argue in court against a warrant or order before it was authorized. In cases where national security or major criminal concerns were an issue, a special advocate for journalists should be appointed to appear in court and argue on their behalf, she said.

If a warrant were authorized, any information or documents obtained would be sealed and inaccessible to police. The journalist would then be notified and given 10 days to respond to the request and oppose it in court. It would then be up to police or Crown attorneys to prove the information was necessary to the investigation and could not be obtained in another way.

The bill's definition of “journalist” is broad enough to include both reporters working for traditional media and bloggers or journalists working for smaller online news outlets, Carignan said. Under the bill, a journalist is a “person who contributes directly, either regularly or occasionally, to the collection, writing or production of information for dissemination by the media, or anyone who assists such a person.”

Many police forces, including the Montreal police, have policies about monitoring the communications of members of democratic institutions – people like journalists and members of Parliament. Carignan said his bill aims to clarify those policies by providing one standard across the country.

“We need to put this very clearly in the Criminal Code,” he told National Observer.

The committee hearing continues on Thursday. Carignan said the bill should be ready for a third reading before the end of the month, and could be sent to the House of Commons before Easter.

This is something that is

This is something that is obvious to many of us who still like to be informed by newspapers as well as TV journalists. We need investigative journalism more now than ever as corporations, companies, individuals as well as our representatives in municipal halls and federal and provincial offices go to a lot of trouble in hiding illigitimate profits, and details of some of their policies.

Comments