The warning signs were there.

In the months before Olivier Bruneau was killed on the job, his loved ones say he told just about everyone he knew that his workplace was dangerous.

Bruneau was 25 at the time of his tragic accident, on March 23, 2016. He was struck by a large chunk of ice that detached from a wall in the construction pit where he was working. It’s the site of a new luxury condo tower in the Little Italy neighbourhood of Ottawa.

“Since the winter holiday season in 2015, Olivier talked to us about the ice all the wtime,” Katia St. Jacques, who was Bruneau’s partner, told National Observer. “Even friends of my parents — after the accident happened, they told me: ‘we saw him two times in our life and that each time he spoke to us about ice.’ He was really concerned about it and there was an accident before — a worker who was struck by ice. This previous accident wasn’t as serious but the guys were concerned on the construction site.”

Bruneau is one of an estimated 1,000 people in Canada who are killed on the job every year. Laws exist to prevent these accidents from happening and punish those responsible, but labour union activists say the government needs to do more to ensure that rules are enforced.

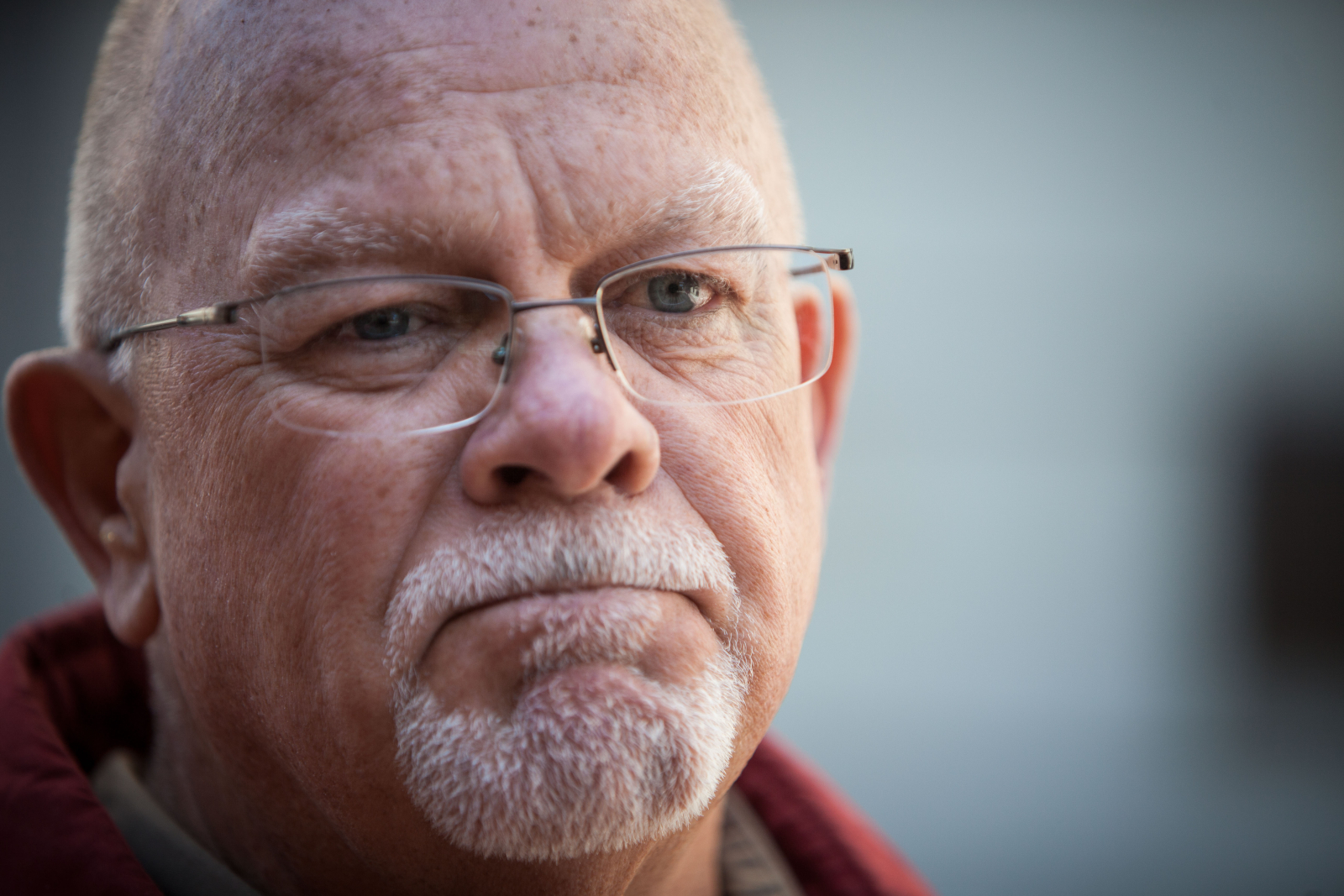

“What’s really hard in cases like these is that the person who you love has passed away, and you can’t find out what happened,” said Christian Bruneau, Olivier’s father.

Allen Martin says he gets frustrated when he hears stories like the tragedy that struck Bruneau and his family. Martin’s brother, Glenn David, was one of the 26 people who were killed on May 9, 1992, when an explosion rocked the Westray coal mine in Nova Scotia.

That incident was one of the deadliest mining disasters in Canadian history. About 10 years later, it inspired new legislation. The Westray Law made it possible to prosecute corporate criminal negligence under the Criminal Code.

But only four cases have resulted in convictions, according to the Canadian Labour Congress, an umbrella organization that represents labour unions. Two of the cases were in Quebec, one in British Columbia and one in Ontario. The latter case from Ontario was a construction accident and was the only one which resulted in a prison sentence, the CLC said.

Hassan Yussuff, president of the CLC, said at a news conference last Monday that law enforcement authorities needs to treat these cases as criminal matters.

“Let me put it another way, long before we amended legislation to make drunk driving a criminal matter it used to be treated as a social problem,” Yussuff said. “Once the legislation was changed, drunk driving was seen as a criminal matter.”

Labour union activists have also urged governments to improve training for investigators and prosecutors to deal with these types of cases.

“It has to be treated as a crime scene,” said Debbie Martin, who was Glenn’s sister-in-law. “You can't let the company take control and destroy the evidence, which is what happened at Westray.”

Twenty-five years after that accident, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government says it recognizes there’s a problem and that it intends to fix it

“We will do more to ensure that labour inspectors and law enforcement officials are properly trained in the provisions of the law, and that they coordinate effectively to ensure that the possibility of a charge for criminal negligence resulting in a serious injury or death is not overlooked,” said Labour Minister Patty Hajdu and Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould in a joint statement released late Thursday.

The government also pledged in its last budget to improve protection for vulnerable workers who file complaints about labour standards in order to make workplaces safer.

"We’ll make sure that employers who repeatedly violate the (Labour) Code’s requirements face consequences," said Matt Pascuzzo, a spokesman for Minister Hajdu. "For example, employers who violate the Code’s provisions and do not come into compliance voluntarily will face monetary penalties and employers who violate the Code repeatedly could also have their names and other information published in the public domain. In the long-run, the amendments will mean fewer injuries and fatalities in the workplace and much better treatment for employees."

"Have to start putting people in jail"

The message was timed for Friday's National Day of Mourning for Workers Killed or Injured on the Job.

“We will promote the sharing of best practices in investigating workplace fatalities across federal, provincial, and territorial jurisdictions,” the statement said.

“Our government recognizes that more can and must always be done to make our workplaces safe, and to give Canadian workers confidence in the laws that exist to protect them.”

Ottawa police say they are still investigating the death of Olivier Bruneau, but they haven’t filed any charges yet.

Meantime, the Ontario Ministry of Labour has filed charges under provincial worker safety legislation against the condo developer, Claridge Homes, the construction company, Bellai Brothers, and two supervisors in connection with the tragedy. Neither company responded to requests for comment from National Observer.

Their case is scheduled to return to the Ontario Court of Justice on May 25.

Meantime, both Christian Bruneau and Allen Martin agree that authorities need to make sure that employers aren’t allowed to simply pay a small fine for an accident that could have been avoided.

“Until it becomes unprofitable to do what they’re doing, they’re going to keep doing it,” said Martin.

“And writing cheques is not a problem for them. They’re going to have to start putting people in jail.”

Jail might be part of the

Jail might be part of the answer but not the whole answer. Stats are 5 per 100,000 workplace deaths in Canada. In Europe it is 1.5 (some even lower) per 100,000, in Britain it is 0.51 and even the U.S. is lower than Canada at 3.8 per 100,000. The irony of it all is that Canada started the National Day of Mourning back in 1985 and here were are with the worst stats. Instead of leading the world in safety our killed and injured far exceed those in 80 other countries.

Seems, we Canadians have been sold a bill of goods ...... we aren't as great or compassionate or polite as we have been lead to believe.

It is very disappointing. Where are our politicians? What is going on?

Thanks, Dawn, for the stats

Thanks, Dawn, for the stats from other countries. Your question "What is going on?" needs an answer from our federal politicians. If a company is flaunting the established laws about workers' safety and this action causes death or serious injury then I think a senior management person should serve time in jail.

Let's face it, Worker

Let's face it, Worker Compensation programs were set up as an insurance program to protect employers from liability. Yet its seems like these programs operate quite differently depending on what sphere you are in. In municipal government it seems like the inspectors were always around and throwing out fines at any small infraction. And I also saw employees flagrantly violate safety regulations to the point where they had to be disciplined. On the other hand, it appears that big private employers are able to avoid the inspections and then penalties when an infraction occurs. Just like our provincial and federal governments interfering in the Mount Polley mine disaster or the avoidance of global taxes on foreign speculators. Money talks. But in this particular case, could the worker not have called the local Worksafe office and lodged an anonymous complaint of unsafe work conditions? That should have brought an inspector out to shut down the worksite.

Comments