FOI investigation reveals that senior B.C. bureaucrats seized on the province's rising grizzly bear numbers —disputed by researchers—to "mitigate” the impacts of mining

Senior B.C. wildlife bureaucrats seized upon the province's rising grizzly bear numbers —figures disputed by university scientists — as helpful for new mining, as well as trophy hunts, internal emails reveal.

The Freedom of Information (FOI) released memos were obtained by the Vancouver Observer.

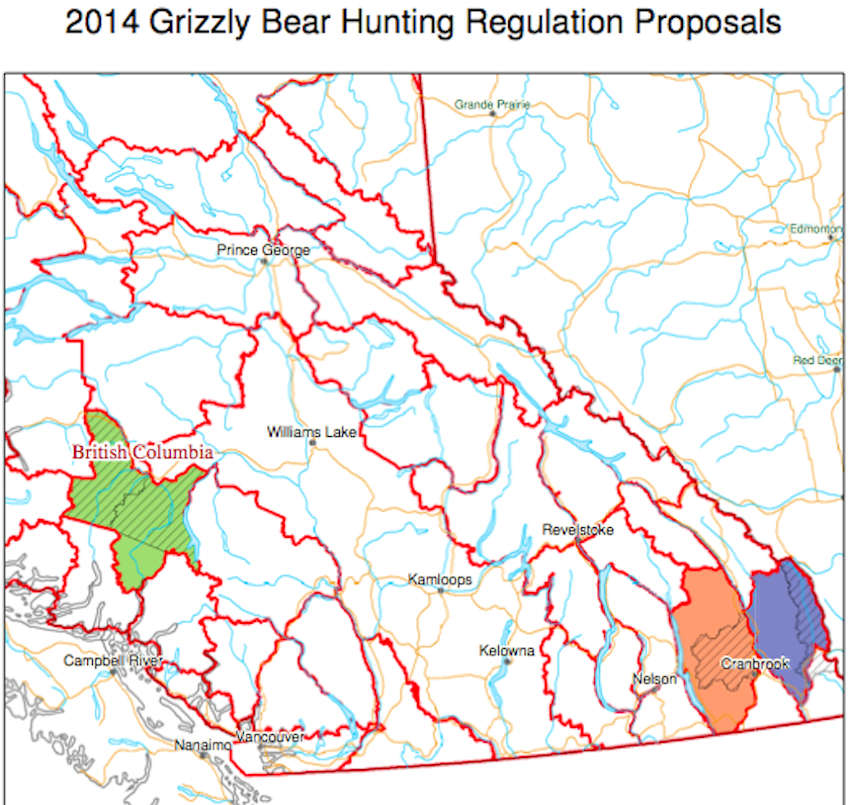

In early 2014, the BC Liberals controversially re-opened the grizzly hunt in two pockets of the province in the Caribou and Kootenay hunting areas. Mining Minister Bill Bennett was also given high-level briefings on January 7 to re-start the trophy hunt, the memos show.

Provincial biologists calculated that grizzlies in the west Chilcotin wilderness were rising by 91 bears over a year prior. So certain bureaucrats appear to have seen that as support for a proposed mine.

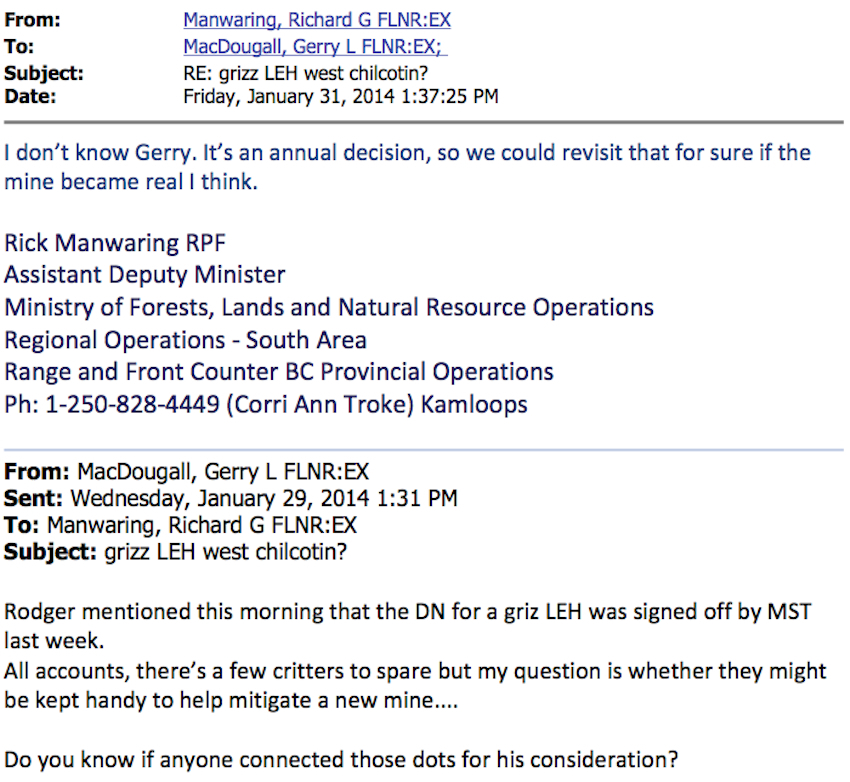

“[By] all accounts there’s a few critters to spare, but my question is whether they might be kept handy to help mitigate a new mine,” wrote Gerry MacDougall, a wildlife manager with the Forests, Lands and Natural Resources ministry, at the time.

"Do you know if anyone connected those dots for [the Minister’s] consideration?” he asked.

Assistant Deputy Minister Richard Manwaring replied: "I don’t know Gerry. It’s an annual [hunting] decision, so we could revisit that for sure if the mine became real I think.”

An active mine proposal at the time was Taseko's "New Prosperity" gold-copper project, until it was rejected last year. A federal panel concluded that there "would be a significant adverse cumulative effect on the South Chilcotin grizzly bear population, unless necessary cumulative effects mitigation measures are effectively implemented."

The mine remains fiercely opposed by the Ts'ilhqot'in Nation, fresh off a Supreme Court land-rights victory.

"Worrisome" use of grizzly data by B.C. government

One grizzly bear policy expert growled at what he sees as the province's odd use of bears for industrial interests.

"This is very worrisome,” reacted Faisal Moola, a forestry professor at the University of Toronto on Thursday.

"They’re using this contested evidence that grizzly bear numbers are increasing, to justify not only a controversial [hunting] activity that a majority of British Columbians are against, but also to justify resource development in those areas as well."

"This shows a real lack of understanding of the science,” he added.

Provincial government map of the two areas opened grizzly hunting in 2014: the Caribou and Kootenay Boundary management areas.

In response to questions from the Vancouver Observer on Thursday, a Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations spokesperson disputed that the director was using the bears to promote resource development.

"[The] interpretation of this email is inaccurate," said Bethel.

Rather, Bethel stated, the wildlife director was inquiring "as to whether other impacts to bear populations (such as habitat disturbance from mining) were also factored into consideration before allowing a Limited Entry Hunt.”

In other emails discussing how to brief Minister Bennett, the same wildlife director repeated the idea that the alleged uptick in grizzly population numbers could be used as a way to mitigate resource-extraction impacts.

“If there is a harvestable surplus [of grizzlies] the Minister of Forestry Lands and Natural Resources could consider those to offset the cumulative effects of resource development,” he wrote.

The presumption of a "surplus" of grizzlies is not shared by everyone. Moola, who doubles as a director general with the David Suzuki Foundation, says scientists doubt the government’s bear count, which suggests there are 15,000 grizzlies in B.C.

A recent study by SFU and the University of Victoria found the province's grizzly count science had a high degree of uncertainty.

Grizzly bears photographed by Andrew Wright.

Pipelines, mining, fracking and logging leave bears vulnerable

But more bothersome, said Moola, is that new mines would mean more roads for hunters to drive in and kill an already threatened grizzly population in B.C. — one of the last places on the planet where the apex predators roam.

"Despite being large and ferocious animals, they are incredibly vulnerable to human activities," he added.

He says B.C. grizzlies are mainly killed in two ways: 90 per cent from hunters, and the rest from industry "punching roads into their wilderness habitat" to create access for logging, fracking, mines and pipelines.

Bears get hit by trucks, trains, and get into conflict with people at dumps and work camps where they are often shot as problem bears, he added.

One study found grizzly bears in central B.C. tended to die close to roads.

Provincial briefing notes also reveal ministers were given message tracks that said the trophy hunt was based on "sound science" — wording repeated to a Global TV reporter when asked if the shooting of grizzlies just for sport was immoral.

The province maintains its grizzly counts passed the sniff test in peer-reviewed studies in scientific publications.

Still, the FOI e-mails also show BC officials scrambling to respond to an increasing maelstrom of negative media reports about the Liberals plan to re-open the grizzly hunt.

The Caribou wilderness area had been off-limits to grizzly hunters since 2000, due to over kills by people.

“We are getting some press over the proposed grizzly regs that have gone up on our website. Can some one make sure Minister Bill Bennett is fully briefed and aware of this? Thanks,” wrote Forestry, Lands and Natural Resources Minister Steve Thomson on Dec.9, 2013 to his staff.

Government biologists bristled at news reports attacking their models that said their bear numbers do not add up.

“The Canadian Press sure lapped it up, anything critical of the grizzly bear hunt gets top billing,” wrote the government's wildlife research ecologist Bruce McLellan.

Comments