Canadian credit rating agencies are failing to properly address the financial risks posed by climate change in their assessment of corporate credit ratings.

Neglecting climate risk factors in their analysis of company credit worthiness encourages irresponsible lending to parts of the industry that are in terminal decline.

While their international peers examine what the impact of the Paris Agreement will be on business models of high emissions companies, and knock-on impacts for investors in and lenders to the hydrocarbon sector, Canadian rating agencies appear to be ignoring these risks.

This is dangerous because it indicates the potential for a build-up of systemic risk in the Canadian financial system.

In their June 2016 assessment of Canadian insurer Manulife, DBRS, a Toronto-based credit rating agency, examine Manulife’s investment exposure to the Canadian oil and gas sector.

Manulife has the largest exposure to oil and gas companies when compared to their Canadian peer group.

Yet the DBRS commentary does not mention significant downside risk to the hydrocarbon sector posed by action on climate change policy. It does not discuss any other risks to Manulife’s investments arising from the transition to zero emissions energy systems agreed to in Paris, and reaffirmed by the prime minister last week in Ottawa.

The published work of DBRS and their peers indicate that Canadian credit rating agencies do not assess the same climate change and low-carbon energy transition risks that are considered by their international counterparts.

This disregard for a major risk category encourages more and more lending to highly distressed segments of the fossil fuel sector.

Maintaining “investment grade” ratings on oil and gas companies that will not be able to operate in a world that is transitioning to clean energy threatens the risk assessment process that forms the foundation of our financial system.

The power of ratings agencies

Credit rating agencies provide an evaluation of the credit worthiness of public companies.

They assess a company’s ability to make timely payments on their debts. The role of ratings agencies is to convey information regarding the relative safety of a company as a credit risk. Rating agencies function as certifying agents who offer their reputation to supplement that of the company as a guarantee of quality to market participants. This unique role and the highly concentrated nature of the industry gives them great influence over how capital is deployed across the Canadian economy.

Regulators and government-backed lenders regularly refer to corporate credit ratings in the fossil fuel sector that fail to consider material climate change policy risks.

Canada’s largest commercial banks and insurers point to the ratings agencies’ strong prognosis for the oil and gas sector as a reason to extend further debt to already heavily indebted companies - with neither the banks or rating agencies willing to publicly acknowledge the business implications of climate change policy action and clean energy innovation, the sector-specific and systemic financial risks are growing.

The Global Financial Crisis and the potential for conflicts of interest

Since credit rating agencies act as intermediaries between companies issuing debt and investors, they sometimes act on behalf of both parties - they may be paid by a coal or oil sands company to rate the quality of the debt being issued by that company.

As witnessed during the US subprime mortgage crisis, rating agencies may be tempted to downplay the credit risk of companies or investment products and to instead inflate their ratings in order to retain business.

In response to negligent ratings on mortgage-backed securities and the resulting financial crisis, the US introduced legal liability for rating agencies who publish deliberately misleading or false information.

This did not happen in Canada.

In the face of significant business risks linked to climate change policy and an economy-wide transition to clean energy, we have have to ask why Canadian rating agencies appear to be ignoring the credit risk elephant in the room.

The world’s largest credit ratings agencies are acting on climate risk

In contrast to DBRS’ troubling risk-blindness with respect to climate change, global players in the industry are analysing the risks.

The world’s largest ratings agencies, Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s, assess climate and energy transition risk factors.

Brian Cahill, a Moody's Managing Director and Head of the Corporate Finance Group for Asia Pacific is clear why: The near universal adoption of the Paris Agreement substantially increases the likelihood of coordinated and effective policies to materially reduce carbon and other greenhouse gas emissions over time, which has in turn the potential to become a significant ratings driver in a broad set of industries.

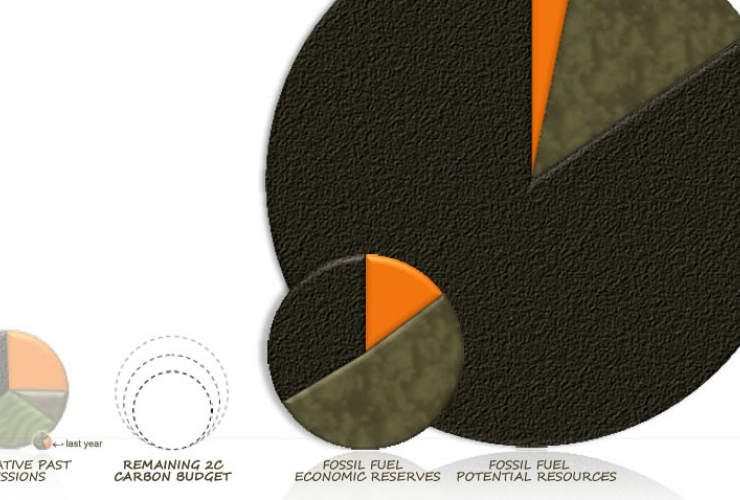

Moody’s credit risk models now include a baseline scenario that forecasts the global emissions pathway if all countries were to implement their national contributions put forward as part of the Paris Agreement. Guiding nationally determined contributions of each country, the Paris Agreement aims to keep global warming to well below 2°C. This requires greenhouse emissions to drop to net zero around 2050.

In recognition of the need to act on these targets, G20 member states - representing the world’s largest economies - have agreed to phase out the use of fossil fuels. This a huge departure from the “business as usual” policy and emissions trajectory that Canadian hydrocarbon producers use in their financial models. This has serious implications for their creditworthiness.

Why do DBRS and their peers in Canada appear to be ignoring these significant downside risks?

For Canadian rating agencies, banks, and insurers who have chosen to keep their heads in the sand on climate change related credit risk, it is time to pay attention. Moody’s identifies four low carbon energy transition risk categories that responsible professionals should consider in assessing the credit implications for corporate and infrastructure debt instruments:

These include: (a) policy and regulatory (un)certainty regarding the pace and detail of emissions policies; (b) direct financial effects, such as declining profitability and cash flows, due to higher research and development costs, capital expenditure, and operating costs; (c) demand substitution and changes in consumer preferences; and (d) technology developments and disruptions that cause a more rapid adoption of low-carbon technology including clean energy. All of these factors are present in the Canadian energy sector.

For the most exposed sectors including coal, high-cost tar sands oil producers and service companies, material credit impacts and rating adjustments are already being felt.

As the transition to solar, wind, geothermal, and other clean energy sources accelerates alongside growth in electric vehicles, existing demand projections for fossil fuels in both power generation and transport will have to be adjusted.

Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s, and the International Corporate Governance Network are all explicit on how climate policy and the energy transition impact on risk models and cash flow projections in the oil and gas sector. It is time for their peers in Canada to meet the professional standards of care, diligence and skill and do the same.

Note: This story was changed from 'analysis' to 'opinion' July 5.

Comments