Recovered and back to school

Scroll down to continueWinston Karam, 16, stands outside Broadview Public School in Ottawa on July 20, 2016. It's the first time he has returned in four years after being victimized by vicious bullying and racial slurs. Story and Images by Mike De Souza.

Winston Karam is polite, soft-spoken and calm when he speaks about what happened to him in the hallways and classrooms of his old school.

The tall, lanky sixteen-year old and his mother, Vania, meet me outside Broadview Public School in a suburban Ottawa neighbourhood on a sweltering Wednesday afternoon in July.

It’s the first time Winston has returned since a precedent-setting court decision found school authorities were negligent as he suffered months of bullying. The judge described the principal's testimony as "obtuse" and ordered damages paid to the family.

Winston and his mother say the school blamed the victim when bullies targeted him with violence and racist slurs four years ago.

Two boys put him chokeholds, they bashed his face into a water fountain, they threw a basketball at his head and they called him the N-word. It went on for months

He went repeatedly to teachers and the principal for help, but instead was blamed and punished, he says. The school even gave him detention for causing the problem.

“One time, one of them called me the N-word and I was sent to the office for saying f-off,” Winston says. “I felt like the whole time they (school officials) were trying to put the blame on me so that the blame wouldn’t be put on them.”

Winston and the two boys who bullied him were initially friends at the beginning of the school year. But their relationship deteriorated after Winston’s mother reported the other boys had stolen some small items from their home. Ferocious attacks followed.

By late April 2012 it had escalated to the point that Winston had a panic attack after one of the boys insulted him and pinched him on the back of the neck in the middle of a class. He still remembers breaking down in tears, hyperventilating and being paralyzed in fear.

The school officials decided not to call an ambulance, instead calling his mother to pick him up. They cleared the classroom as the principal and some other teachers tried to calm him down.

But he feels they made things worse.

“The way they were saying calm down, (they) acted more like they were angry at me for crying and hyperventilating, more than they were worried about me,” he says.

A school in denial

Scroll down to continueWinston Karam stands outside his home in Ottawa on July 16, 2016.

Winston now stands tall at 6’1. He shot up in the past few years, his mother says, and started working out with weights and doing self-defence training to build his confidence. He lost one year of school as he recovered.

Things are better on this sunny day, as he looks around at his old surroundings. He notices a few changes to the neighbourhood. There’s a new building beside the school in a spot where he remembers a small baseball field.

Winston no longer shows signs of being upset and has learned how to accept what happened. He now knows what he needs to do in case it ever happens again.

The school board says it has taken steps to address how it deals with bullies since Winston was targeted. But it also fought tooth and nail against the legal action launched by the Karams. The school board and its lawyers from an insurance company appealed an earlier court defeat, denying for years that they had done anything wrong.

Vania Karam produced emails in court showing how she had tried to reach out to school officials appealing for help.

After Winston's anxiety attack in April 2012, she wrote to the principal and two senior school board officials - superintendent Francis Wiley and chief executive officer Jennifer Adams asking for help. She also told them she wanted an apology for their lackadaisical response to the situation.

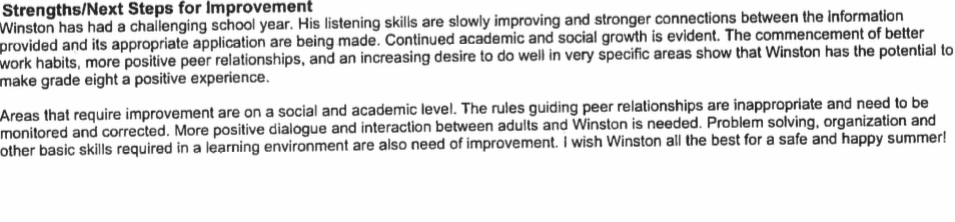

The school responded by criticizing Winston that year in his final report card dated June 29, 2012.

“... peer relationships are inappropriate and need to be monitored and corrected," the school wrote in the report. "More positive dialogue and interaction between adults and Winston is needed. Problem solving, organization and other basic skills required in a learning environment are also need (sic) of improvement. I wish Winston all the best for a safe and happy summer!”

Vania Karam says she saw this report card as an attempt to blame the victim. It was the last straw that drove her to the courts.

The school board was forced to end its denials on May 24 this year when an Ontario Superior Court concluded that school officials and teachers were negligent for ignoring Winston’s problems and failing to protect him from bullying. The court ordered the school board to pay about $3,500 in damages to the Karam family in a scathing decision that concluded the school officials were lacking credibility.

The legal team working for the Karams say it’s the first reported North American case of a court ruling that blames an institution for turning a blind eye to school yard bullying. It may set a new standard for all schools across the continent.

Tami Cogan, a paralegal hired by Vania Karam, says the lawyers were only able to find one similar case in Australia.

Cogan specializes in education law and has had some other experiences involving school boards that were reluctant to deal with bullying issues in court. So she believes this would make it a precedent-setting case that will raise the bar - at least for schools in Ontario.

"This case will be very beneficial in dealing with school boards across the province," says Cogan.

Vania Karam also says she had hoped that the school board's top officials would have shown some more accountability.

When I ask the school board questions about the case, it responds with a statement explaining that it now hopes to learn from the unfortunate incidents and improve its practices.

According to the Ontario government's sunshine list, Adams, the school board's chief executive, earned a salary of over $242,000 last year while Wiley, the superintendent, earned more than $162,000.

Neither were available for interviews to speak about what went wrong.

Justice costs a lot of money

Scroll down to continueVania and Winston Karam outside of their town home in suburban Ottawa on July 16, 2016.

A few days before I met Winston and his mother at the school, I sat down with them outside on the front lawn of their three bedroom town home across the city on the eastern side of the Ottawa.

They live here with Vania’s mother who is suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. They moved to this neighbourhood in 2012 a few months after all of the bullying.

The move gave Winston a fresh start at a new school.

Vania Karam, 42, is an economist who works for the federal government as an accountant. As a sole-support single mother, she says she has spent more than $50,000 of her own money just on the legal fees for this case. She still has much of it left to pay, but believes she can pay off the debt over the coming months.

“I paid a lot of money to get this judgment and I paid a lot of money to get Winston a voice and have his voice finally heard,” Vania says flatly. “I’ll tell you that justice costs a lot of money.”

But she smiles when she talks about the moment she heard the ruling delivered in the small claims division of Ontario Superior Court by Deputy Judge Rohan Bansie last May 24.

The ruling made it clear that the judge did not find the school officials were credible. The court found that they were offering contradictory testimony and it was clear they had failed in their duty to protect Winston.

“When I heard the judge giving his ruling and when he said that the principal’s testimony was ‘obtuse, rote and inconsistent,’ I really felt, ‘wow, I just received justice.' No matter the cost of it, I really felt good about that. And I don't know if you can describe that feeling, unless you’ve actually received justice on something. It feels really, really good.”

The feeling is a sharp contrast with how she felt after she was called into pick up Winston in April 2012, following his panic attack.

“When he came home that weekend he was so withdrawn and upset about it, and I really felt that I had to be stoic that weekend to kind of get him through,” Vania says. “But I’ll tell you that when I went back to work on Monday - the moment that I dropped him at school and we had our team meeting and I just broke down crying. It was too much for me.”

She says that the bullying got even worse when he went back to school, forcing her to withdraw him from classes and homeschool him for the remainder of the year.

Then she had to pay for counselling and self-defence training for Winston to help him recover.

Vindicated

Scroll down to continueVania and Winston Karam chat about their experience outside their home in Ottawa on July 16, 2016.

But Vania Karam thinks her legal battle and its astronomical costs were worth the ordeal. She notes with sadness that there’s already been at least one child in the Ottawa region who committed suicide because of bullying in recent years, and that more than a dozen other similar cases were reported in the same time frame across the continent.

She says that there’s no way to put a dollar value on all of these lives.

“Say I hadn't done anything and nobody was held to account on this, what message would that have sent Winston for the future,” she says. “I don't know if he’d be in such condition as he is now if he hadn't been vindicated."

She maintains that throughout the ordeal, the school was failing miserably in its efforts to help Winston and instead turned the blame on him.

She cites examples such as incorrectly putting a flag on his file that he had an anxiety disorder and even suggesting in one of his report cards that he needed to improve how he dealt with adults.

Vania Karam never received a response to her letters to school officials asking for help.

And when she initially won her first case against the school board, it appealed the ruling, setting the stage for the May decision, which they finally accepted.

Vania and Winston have still not received any apology from the school board, nor have they received any of the money that the court ordered it to pay. But in a statement, the board says it’s working on that as it also engages in various initiatives to prevent bullying and discrimination.

“We believe this work is making a difference,” says Ottawa Carleton District School Board spokeswoman Sharlene Hunter, in an email. “However, the recent court decision highlights the importance of our work in this area and the need for continued growth. As a learning organization, we will be reviewing this decision in detail to help identify opportunities to improve our practice and provide further professional development. Unfortunately, we cannot undo this experience, but we can learn from it to better support all students and families.”

Hunter adds that the school board has followed up with its insurance company, which represented it in court, and have asked them to ensure the Karam family is paid as the court required.

Stopping racism, a precedent for North American schools

Scroll down to continueVania and Winston Karam smile outside of their Ottawa home on July 16, 2016 after speaking about how they succeeded in getting past their ordeal.

Winston shrugs and shakes his head as he reflects on what it all meant.

“If a white person can call a black person the N-word at such a young age and not be reprimanded for what he had done and nobody is getting mad at him for doing that, I definitely feel that’s where racism is going to start. And later on in life they’ll think: ‘Oh, I could call somebody the N-word. Nobody acted on it back then, why would somebody act on it now?’”

At the same time, he says it’s very easy for victims to think that racism is acceptable if no one steps in to defend them.

“That just shouldn't be happening.”

Vania Karam says she felt there was a lack of sensitivity shown by school board officials about the bullying and racism.

Right now there is not much diversity on the board's leadership team. Board spokeswoman Sharlene Hunter says reflecting the diversity of students in the classrooms is a priority and that the organization is working hard to retain and hire candidates that would help it meet that objective.

Hunter adds that the school board has changed some of its practices since 2012 when the bullying occurred, improving training for staff as well as introducing new anti-bullying programs.

"We take issues of bullying very seriously and have many excellent initiatives in place to assist with this work," says Hunter. "This particular case is a reminder that our work in this area must continue."

The programs included surveys of students from grade four to 12, that ran from September 2012 to the end of 2015 to understand their concerns about bullying and whether they felt safe, Hunter explained.

Meantime, Winston says that things are much brighter for him these days. He even has some advice for others that wind up in his shoes.

“Just remember that it’s not a downhill slope after bullying. If you have the right crowd around you and you have the right people supporting you, things go up after bullying,” he says. “I made a couple of friends after. That definitely helped me cope and helped me forget what happened that year and helped me heal. I also have a great family that helped me heal as well.”