Mazhar Aldarwish is a stocky, mustached man. He speaks in a rumbling baritone voice that makes one think of an Arabic-language radio program host.

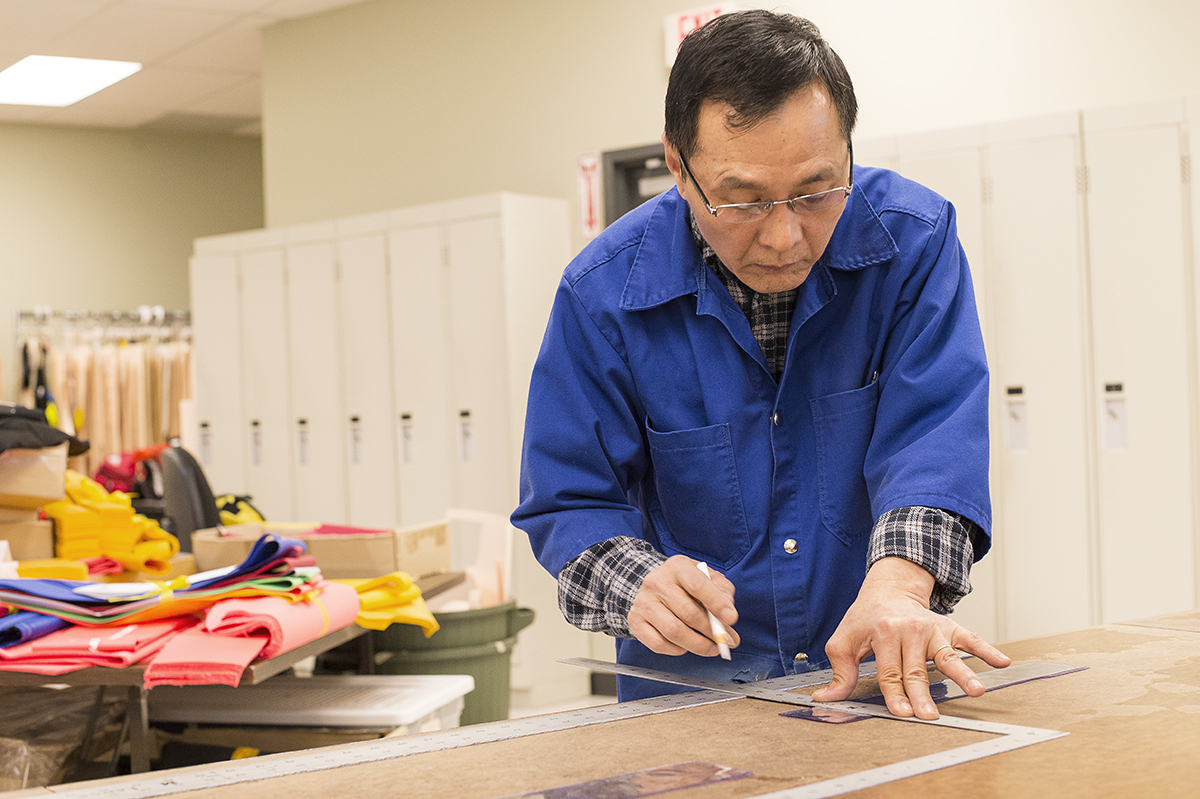

He and his colleague Ahmad Hwichshan have just come back from coffee break on their jobs making emergency preparedness kits for government organizations and private companies, such as the Canadian Coast Guard, Parks Canada, and Vancity Credit Union. A former heavy equipment operator from Homs, Aldarwish is among four Syrian refugees employed at First Aid and Survival Technologies Limited (F.A.S.T.). Started in 1988 by two women, the Canadian-owned and operated company is the largest custom emergency management and safety solution provider in Canada.

Aldarwish hit the ground running when he arrived in Canada in December, starting his new work at F.A.S.T. in January.

He was introduced to his employer through a sponsor, while Hwichshan, who has been at F.A.S.T. for six months, signed up thanks to an eight-week training program run by B.C. Alliance for Manufacturing, which pairs trainees with Canadian companies. Funded by Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) through the B.C. Ministry of Jobs, Tourism and Skills Training, the course has helped refugees across B.C. find jobs and training to prepare them for Canadian workplaces.

While he and Hwichshan are on the ground floor, his Syrian colleagues Firas Najib and Hamed Alshhadat are on the second floor, where sewing machines are humming away. In this large facility beside the Fraser River, the ambiance is professional but relaxed and friendly.

F.A.S.T. operations manager Monica Mortimer said the Syrian refugees have been a great fit in the company's 30-member workforce. After initially hiring two Syrian refugees last year, they've worked out so well the company decided to hire two more.

"Language is really not a problem here," Mortimer says emphatically during a tour of the facility. "One of our workers, Florence, is deaf, and she really taught everyone how to communicate using gestures. And Florence and Ahmed actually take the bus together to come into work. They understand each other and watch out for one another."

For refugees like Hwichshan and Aldarwish, the work at F.A.S.T. is more than a job. It's a new lease on life after fleeing the six-year Syrian conflict, which has so far displaced over 11 million people. Aldarwish vividly recalled in an interview with National Observer the harrowing experience that put his family on the path to Canada.

"My soul came back inside my body."

Aldarwish's large brown eyes pool with tears as he recounts the most difficult day of his life — the day he learned terrorists had captured his son for ransom.

“My son was a taxi driver, and one day on the job, he was kidnapped. The kidnappers called me saying they wanted $20,000. He’s my only son. I sold everything I had to raise the money. Then, for three days — nothing. There was no way to get in contact.”

“My one and only son,” he repeated, his voice shaking. “I don’t have any others.”

When he delivered the money to the kidnappers and his son was returned, Aldarwish said there were no words to describe the feeling of relief that swept over him.

“I felt like my soul came back inside my body.”

His son's kidnapping pushed Aldarwish to get his family out of their hometown. Homs is Syria's third-largest city, once a vibrant industrial hub with a rich Christian heritage dating back to the fifth century. He made his son flee Syria the very next day, and took the rest of his family to join him in Lebanon for four years. Life there was difficult, he says, because Syrian refugees officially aren't allowed to work. Those who do are often exploited and underpaid, but remain quiet out of fear.

Aldarwish goes to work each morning now feeling he can breathe. His daughter and son, both in their mid-twenties, are in Canada, and rapidly picking up English in school. Asked the most striking aspect of his new life in Canada, he marvels:

"There's so little discrimination here. People from different backgrounds are treated equally," he said.

Refugees: a good fit

During the workplace tour, Mortimer points out a kitchen where women are cooking emergency food, and a pile of grey-stained red emergency bags, which B.C. firefighters bring to F.A.S.T. for cleaning and maintenance. She says Canadians often imagine that sewing and manufacturing orders are outsourced to Asia, but that plenty of design and sewing jobs remain in B.C. because it makes more sense to work with local businesses if they're not producing massive orders.

Asked if it was part of F.A.S.T.'s company policy to hire Syrian refugees or to maintain a certain level of diversity, Mortimer blinks in surprise.

"No, there's no company policy," she says, smiling. "It just kind of worked out that way."

"We're always looking for more people who can sew," Mortimer adds. "Right now, we really need an upholsterer. So if you know of anybody who has these skills, let us know."

Aldarwish hopes to one day get back into the construction business. Other Syrians came to F.A.S.T. with experience in the sewing and garment industry.

Hwichshan owned two garment factories and his own successful clothing brand before the war. "Wholesale," he explains, pointing to his own red jacket to explain the kind of clothes he made.

Having set up his brand with $500 U.S. dollars, he worked 14-hour days running his garment business, and once owned two large homes and a farm. "Well, all that's gone now," he laughs nonchalantly, playing down his loss.

Firas Najib, an upbeat man who recently volunteered to help his mother and sister at a catering event, used to oversee a clothing factory for major international brands such as ZARA and MANGO. Of the four Syrian newcomers at F.A.S.T., Najib speaks most easily in English, having worked in Dubai before coming to Canada.

With pride, Najib pulls out his phone and shows photos of fashion models wearing the clothes made at his factory, and a clothing rack filled with colourful men's dress shirts that he made. "I wish I could hold a fashion show one day," he sighs, adding that it's his dream to have his own clothing brand.

Hamed Alshhadat, who works alongside Najib, started work in tailoring before going to university to study history.

"I've always liked this kind of work. People told me I was good at it from an early age," said Alshhadat, who began working at a local tailor shop when he was 12. His new job isn't as complicated as sewing fashionable clothes for customers, but to him it is meaningful work.

"It makes me feel good to know I'm making equipment to help save lives in Canada," he says.

Labour shortage for manufacturing jobs

Refugees help fill a significant labour shortage in B.C.'s manufacturing sector.

Marcus Ewert-Johns, chairman of the B.C. Alliance for Manufacturing, says over 50,000 manufacturing jobs will be opening up by 2025. Through partnership with MOSAIC, a B.C. charity that helps newcomers settle in Canada, the Alliance trained 40 refugees last year as part of a pilot project, and 65 people are going through the course today. Although the program isn't limited to Syrian refugees, they make up the majority of participants, while others have come from Iraq and parts of North Africa. After initial screening, the refugees learn the dos and don'ts of Canadian workplaces, including cultural training, and learn basic English language required for the job before getting a tour of some companies looking to hire them.

Ewert-Johns says around 18 B.C. companies are taking part in this program, and companies often recruit more than one refugee, with one company hiring six in one go.

"Our member associations represent businesses who are employers. Generally, when we have meetings and discussions, the number one topic is always, ‘I need workers, I need workers.'"

Ewert-Johns said jobs in the manufacturing industry typically pay better than the minimum-wage jobs in the service industry, which helps Syrian refugees with families to feed. Because Canada excluded unaccompanied single men from coming in its Syrian refugee screening process, many of the people enrolled in the program are men with dependents. According to Immigrant Services Society of B.C., the average family size of the first wave of government-sponsored refugees was six people. Out of the government-sponsored refugees in B.C., around one in five have found a job before the end of their first year, despite many families having to wait months to get access to housing or English-language classes.

He said even if Canadian workers flooded the manufacturing industry today, there would still be a huge shortage of workers that can only be filled by newcomers. Many newly-arrived refugees are desperately looking for work. The trouble, he says, is a severe lack of English and other training classes.

"We don’t have a problem finding job vacancies for refugees. But we need funding for more class spaces and instructors to train more people. There are companies that tell me, 'can you get me like 15 people tomorrow.' We would, if we could! But we're only training 40 refugees at a time."

"You hear some people say refugees are draining our social welfare and taking jobs away. They're not," Ewert-Johns said. "These are the people our economy critically needs to pay so we can generate tax dollars to build our roads, schools, education and health care system that we all rely on here."

Asked if this shortage of workers is a new development, Mortimer at F.A.S.T. says her company has always struggled to find workers because Canadian job hunters tend to overlook sewing as a viable option.

"In a lot of cases, people don't consider this a career. People who go to college learning how to be a fashion designer aren't looking for jobs like this. They want to get into Lululemon. What they don't realize is that we actually do a lot of of design work here."

Mortimer says even though the starting wage at F.A.S.T. is minimum wage, the rate goes up with seniority and that many of the staff have been here 10 or 15 years, some since the company's inception.

"The ladies here have bought homes and raised families on these jobs. You can make a good living here. It's good pay when you work your way up."

Mortimer said when she learned about the refugee training program, she leapt at the chance to hire new people. The company will soon need more workers to keep pace with production orders and attrition.

"A lot of people are going to be retiring soon, so we're trying to get younger people, people who can still be in the workforce for another 10, 15 years," Mortimer said.

Etab Saad, an employment counsellor and facilitator for Syrian refugee projects at MOSAIC in partnership with BC Alliance for Manufacturing, said many refugees already have relevant work experience in the manufacturing field.

"We have welders. We have people who assembled furniture, and people who used to do sewing,” she said. She said the program helps give initial training, but that refugees who obtain and retain their jobs do so through their own determination to succeed.

Respect for workers in Canada

All four men spoke during separate private interviews about how they are fairly treated and valued at their workplace.

"We have rights here," Alshhadat says. "Our employers treat us fairly, and give us coffee breaks and lunch breaks. This never happened to me before. I used to be at work from 8 a.m. until 8 p.m. with no time to eat anything other than a quick sandwich. And we feel treated like equals with other staff."

Najib realized how much his employer cared when he felt weak one day at work.

"I cannot find a kidney right now, so for nine hours, I'm on a dialysis machine at night," he said. "One day, I felt dizzy at work. Monica (Mortimer) was worried. She told me to go home, relax for three days, come back and work. She told me, don’t worry about this. Relax and after, come back."

He was moved by her concern and courtesy.

Work and social integration

Right now, each of them is free to think about the future in ways they couldn't before. Najib eventually wants to enroll to school to upgrade his skills. Alshhadat's two daughters, aged two and four, are about to go to kindergarten, and he's looking for a new place to live.

Hwichshan lights up with excitement as he shows off photos of his two children on his phone.

“My eldest is really into video game design,” he says, beaming at the sight of his young sons' faces. “He did his own research online to figure out that (video game company) Electronic Arts is located in Burnaby. He’s a smart kid. I have high hopes for him.”

Ben Kuo, a University of Windsor psychology professor, said jobs are extremely important for new refugees to integrate smoothly into Canadian society. Kuo is involved in a five-year intensive study on how Syrian refugees are settling into Canadian life.

"The refugees need to have meaningful, gainful occupation," he said."Regardless of where you are, if you don't have basic financial resources, all the other things become secondary."

He said Canada is so far doing a "fabulous job" compared to many other countries, some of which prevent refugees from working. But this integration requires resources and planning, like the jobs training program in B.C., to ensure unemployment and social marginalization don't become problems down the road.

In a March 2016 European Parliament report, Labour Market Integration of Refugees, authors note that participating in the workplace is "the most significant factor favouring long-term integration into society" and that refugees' workplace integration is also "central" to contributions by refugees to their new home country's economy. Although it takes initial investment by governments to help refugees in the short run, the report warns that not investing early in helping refugees find jobs sparks the "risk of a long-term integration failure" and "political costs of a massive political polarization."

But according to preliminary research by University of British Columbia geography professor Dan Hiebert, who studies international migration and its impact on Canadian cities, refugee employment is at the same or higher level than that of Canadians once they settle. According to 2011 Statistics Canada figures, 63 per cent of the total population between 18 and 65 are employed in Vancouver, compared to 69.8 per cent of Vancouver-based refugees.

"Long term career training and re-entry programs need to be present for Syrians to gradually enter into the Canadian workforce.That's very important," Kuo said. "Because these refugees are so new, we don't know what this will actually look like, but our governments and communities can start planning today. We'll see the impact this will have in several years, so it's important to start planning now."

Comments