Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in The Energy Mix on Wed. Jan. 24, 2018. It was republished with permission.

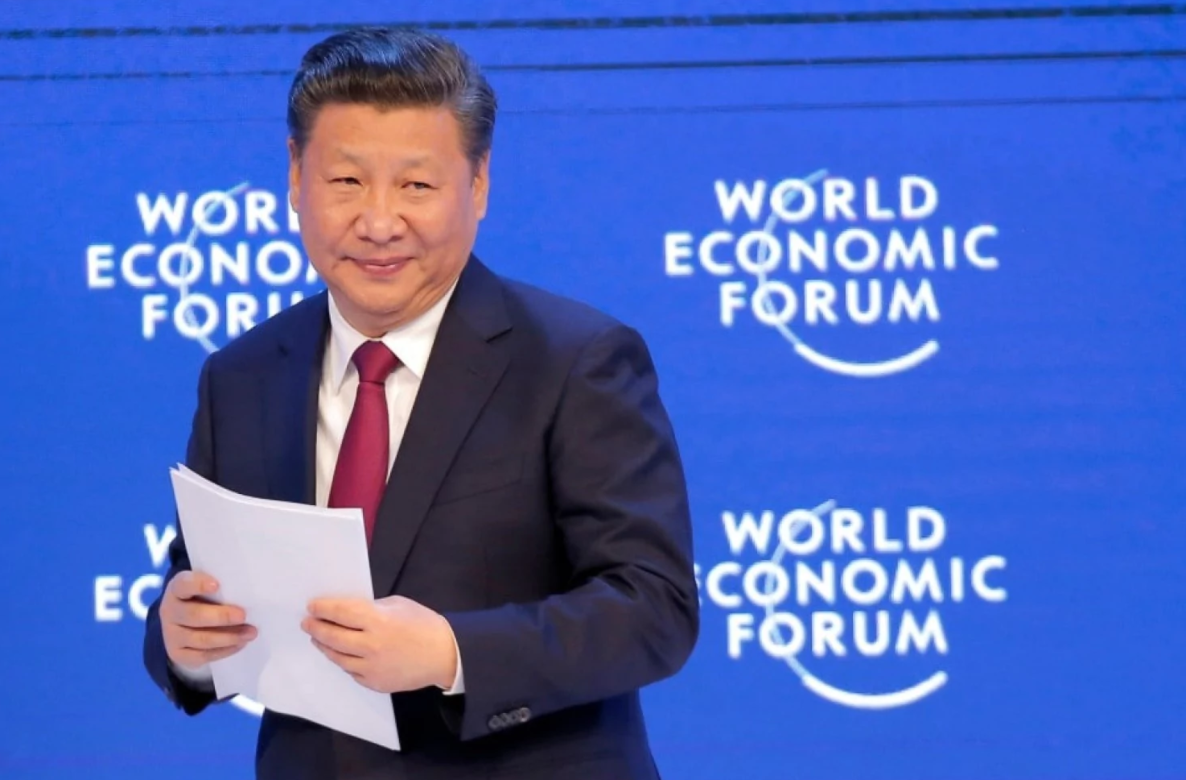

Days before setting off to Davos to address world leaders attending the 2018 World Economic Forum, U.S. President Donald Trump fired what may come to be seen as the opening shots in a global trade war — choosing clean solar power as one of two targets for crippling new American tariffs.

The administration used a rarely-invoked trade law that permits the executive branch to impose import penalties on trade partners’ goods, on grounds of injury, even when they have not violated trade commitments. It levied tariffs of 30 per cent and 50 per cent respectively on imported solar panels and residential washing machines, above defined quotas in each case.

Trump’s approach to trade was signalled late last year when the U.S. levied a crippling 292 per cent tariff on aircraft built by Bombardier Inc. He has also thrown the North American Free Trade Agreement into doubt, repeatedly suggesting he will scrap the deal.

But coming just ahead of a much-anticipated speech to the strongly pro-trade World Economic Forum, Trump’s moves could be read as a dog whistle to his nativist political base — and the rest of the world — that he is ready to escalate his bellicose approach to trade even further beyond the rhetoric of his campaign and first year in office.

Is the U.S. reneging on global trade rules?

Under the new measure, the United States will allow 2.5 gigawatts of unassembled solar cells to be imported tariff-free each year. In the first year, a 30-per-cent tariff will be applied to imported cells above the quota, and to assembled panels. The tariff drops by five percentage points per year, to 15 per cent after four years, then remains there.

In a parallel move, the administration imposed a 20-per-cent tariff on the first 1.2 million residential washing machines brought into the country, and a 50 per cent tariff on any additional machines. Those tariffs decline to 16 per cent and 40 per cent respectively, in the third year.

The tariffs responded to complaints by two U.S.-based solar panel manufacturers — bankrupt Suniva Inc. and SolarWorld Americas — and appliance-maker Whirlpool Inc.

In a much-noted irony, while the tariffs were broadly interpreted as being aimed at China, Suniva is majority owned by investors from that country and “the company’s American bankruptcy trustee supported the trade litigation over the objections of the Chinese owners,” The New York Times reports.

U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer justified the administration’s application of Section 201 of the U.S. Trade Act of 1974, saying “the [U.S.] International Trade Commission found that U.S. producers had been seriously injured by imports.”

The United States argues that the section is rooted in Article XIX of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, which it says “permits a country to ‘escape’ temporarily from its obligations under the GATT when increased imports are causing or are threatening to cause serious injury to domestic producers.” But the last time the U.S. invoked the section, against steel imports in 2002, the World Trade Organization subsequently found the measure violated its trade commitments. The George W. Bush administration withdrew the measure.

That may not happen this time.

Tariff will hit workers in Asia

China, South Korea and other countries whose exports are affected “could take their complaints to the World Trade Organization, which settles trade disputes,” The New York Times speculates. “Under its obligations to the international body, the United States would have to back off if the organization ruled against it.”

Or not: “If Washington did not adhere to such a ruling, the World Trade Organization could authorize other countries to set similar trade limits,” the Times notes. So U.S. defiance “could raise the question of whether the United States accepts the organization’s decisions. [Trade Representative] Lighthizer has argued for years that such decisions should, essentially, be advisory.”

Such a showdown on whether the world’s largest economy continues to play by the global trade rules it largely laid down, may now be in the cards.

Although China appeared to be Trump’s intended target, the tariff on solar cells and panels will mostly hit workers in other countries. Thanks to dispersed supply chains — and partly in response to previous U.S. tariffs — solar photovoltaic manufacturing is a global industry. Malaysia, South Korea, and Vietnam all hold a larger share of the U.S. market than China does directly. And all are entitled to seek remedies under various trade agreements.

“Both China and South Korea,” the Times reports, “harshly criticized the move, with both suggesting they could take their complaints to the World Trade Organization.”

A statement by China’s Ministry of Commerce denounced the action: “With regard to the wrong measures taken by the United States, China will work with other WTO members to resolutely defend our legitimate interests.”

Mexico, which has a small five per cent slice of the U.S. solar panel market that is nonetheless worth about US$1.1 billion — and has been given no reason to love Trump’s America — also signaled its strong displeasure at “the United States’ decision not to exclude Mexico from the measures taken today,” Reuters reports. Its economics ministry, in a statement, noted its options under NAFTA to demand compensation if the United States breached its trade commitments.

China, news outlets speculate, may not wait for WTO sanction to reply.

'America First' approach could cost Americans

“China has long been a big buyer of soybeans and other crops from states that supported Mr. Trump in the 2016 election,” the Times notes in a third report. “As an enormous consumer of the world’s goods, it could easily punish American companies that have international competitors, for instance by choosing Airbus planes over Boeing’s or punishing General Motors while leaving Volkswagen alone.”

Much may depend on the Americans’ next move. “The economic impact is not material,” Trinh Nguyen, a Hong Kong-based economist, told Bloomberg Television. “The concern really is whether or not this is a trend with more to come.”

“It shows that the U.S. administration, after taking its time, is now indeed starting to roll out measures restricting trade with the idea of living up to the promises made during the electoral campaign,” Louis Kuijs, another Hong Kong-based consultant, told Reuters. “This could very well be just one step of many.”

Indeed, the Times reports, “White House advisers warned that additional trade measures related to steel, aluminum, and other products from China could be coming, a signal that Mr. Trump is ratcheting up the protectionist policies he has long espoused as part of his ‘America First’ approach.”

Almost certainly, the punitive move will have scuttled a deal the U.S. solar industry had been trying to make to “reset” the U.S.-China price rivalry over solar panels by divvying up some $1.5 billion in previous U.S. tariffs among American and Chinese manufacturers and parts suppliers. According to Bloomberg, the proposal “would call for Trump to drop existing duties on solar panels — and not to not levy new ones. China, in turn, would abandon its own tariffs on U.S. polysilicon, a key solar panel ingredient.”

Already “a long shot,” the idea can be presumed to be an early victim of the White House trade attack.

Meanwhile, solar photovoltaic developers and installers in the United States were among the injured from Trump’s dumpster tariff fire.

The decision “will create a crisis in a part of our economy that has been thriving,” declared Abigail Ross Hopper, president of the Solar Energy Industries Association. It “will ultimately cost tens of thousands of hard-working, blue collar Americans their jobs.” Hopper’s association warned the tariff could slash solar installations in the United States by half, throwing as many as 23,000 people out of work.

Ahead of the decision, Hopper had predicted the tariff would “double the price of solar, destroy two-thirds of demand, erode billions of dollars in investment, and unnecessarily force 88,000 Americans to lose their jobs in 2018.”

Others saw another blow in Trump’s ongoing battering of renewable energy in apparent service to his vocal backers in the fossil fuel sector.

“The tariffs are the latest action by Trump to undermine the economics of renewables,” Bloomberg writes. “The administration already decided to pull the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement on climate change, sought to roll back Obama-era regulations on power plant emissions, and signed sweeping tax reforms that constrained financing for solar and wind. The import taxes are the most targeted strike on the industry yet, and may have larger consequences for the energy world.”

Other estimates were more tempered.

“MJ Shiao, head of renewable energy research for Wood Mackenzie, said the tariffs would likely reduce projected U.S. solar installations by 10 to 15 per cent over the next five years,” The Guardian reports. “It is a significant impact, but certainly not destructive to the end market,” Shiao said.

Less clear is whether the move will do much to help the companies that instigated the measure, even apart from the risk that they may have set off a global trade war that will leave all countries worse off.

As Washington trade specialist Clark Packard remarked to E&E News, “more good-paying [American] jobs will be jeopardized by today’s decision than could possibly be saved by bailing out the bankrupt companies that petitioned for protection.”

What will it take to produce

What will it take to produce solar technology on shore, in Canada ? I understand the basic economics from 'the old days' but when the effects of climate change speed ever faster our way, how do the economics from 'the old days' count ?

Comments