Lee Johnson is dying.

The 46-year-old former groundskeeper from California regularly handled a popular pesticide called Roundup at his job. On some days he sprayed hundreds of gallons of the formula over several hours around sports fields and schools.

He wore protective gear, but had occasional leaks and significantly exposed his skin to the substance on one occasion. He began experiencing rashes, and then developed lesions.

Johnson, whose first name is Dewayne but goes by Lee, has a wife and two sons. He is now suffering from non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and doctors said this spring it is incurable.

In August, a jury in his state ruled that glyphosate-based pesticides like Roundup have contributed to the development of Johnson's cancer, and that the manufacturer, Monsanto, knowingly hid the risks. The jury awarded him US$289 million in damages, later revised by a judge to US$78 million.

Thousands of internal company documents, now described as the "Monsanto Papers," were released during this trial and other legal action. Johnson’s lawyer Brent Wisner has said they show how the company was involved in manipulating scientific papers about glyphosate's health effects.

The case has repercussions in Canada. The federal pesticides regulator appears to have relied on some of this research prior to approving the use of glyphosate as a pesticide for 15 years in 2017, and establishing how it could be handled safely. It also received dozens of reports alleging a link between glyphosate and cancer in 2016 that may have been triggered by Johnson's lawsuit.

Karen Ross, who leads the pesticides and toxic products program at Équiterre, sits down for an interview with National Observer's Carl Meyer to discuss the Monsanto Papers and their implications in Canada. Video by Alex Tétreault

Canada has reports alleging glyphosate cancer link

By the time the Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) — an agency that operates within Health Canada — re-approved the use of glyphosate on April 28, 2017, Canada had been notified of 68 "serious incidents" from April to October 2016 involving glyphosate where complainants alleged they had developed cancer due to exposure.

Health Canada has told National Observer that it couldn't follow up on these cases, which came mostly from Monsanto itself, because it didn't have enough information to determine whether the effects described were related to pesticide exposure. To determine that, it said it needed details like the amount or duration of exposure, and the timing between exposure and the onset of symptoms.

The department also said it couldn't obtain more information because it didn't have the personal details of the people involved. Asked why it couldn't just ask the company for more information, the department said these details are frequently not even provided to the manufacturer.

“What we have learned is that Health Canada relied on science that was manipulated," said Karen Ross, an expert on sustainable agriculture, in an interview. "Health Canada used this information as independent data, as independent public science, in its decision particularly around the cancer risk of glyphosate."

Ross, who has a Ph.D. from Western University on agriculture and the impacts of organics and fair trade networks on rural sustainable development, is the project manager for pesticides and toxic products at Quebec-based advocacy group Équiterre.

She said the so-called Monsanto Papers raise serious concerns about what scientific evidence was used by the agency, and proposes that the government set up an arm's length panel to review the decision. Pending that review, she said that the government should ban the product's use, since there are doubts about whether it is safe.

Ross also said that the lack of information about the 68 serious incidents demonstrates the need for improved government oversight of the reporting process.

“The PMRA has designed a system for incident reports to factor in to their decisions and measure risks, but yet again, this is an example of the way that Monsanto is interrupting the process of getting proper data on risks to our regulator," she said.

'This isn't independent enough'

Health Minister Ginette Petitpas Taylor’s office says a decision whether to create an arm's length panel to review the decision “will be made in the coming weeks.” Earlier reporting suggested the department had already launched a review of the decision made by the regulator in light of what it called “troubling allegations,” following the news of Johnson's court case.

In fact, Health Canada officials have been reviewing their own work for over a year, as part of an internal process that began before the California verdict.

The department’s internal review began after Équiterre and other environmental and health groups filed a “notice of objection” under the law in August 2017. At the time, Équiterre and the other groups argued that the regulator’s decision to re-approve the chemical was based on an incomplete literature analysis since it failed to consider or dismissed several studies linking glyphosate to cancer, and instead "relied heavily on old data."

But since the Monsanto Papers, it’s clear that such a self-examination isn’t sufficient, said Ross.

“What this means is that public scientists within Health Canada are reviewing a decision that has been made by their colleagues within Health Canada. For us, this isn’t independent enough,” she said.

Thierry Bélair, Petitpas Taylor’s press secretary, said Health Canada’s decision to authorize the use of glyphosate "is based on hundreds of studies from a variety of sources." The department has been reviewing those studies to assess whether “a change to the original decision, or the use of a panel of experts not affiliated with Health Canada,” is justified, he said.

“This is a normal delay considering that the sheer volume of critical information that has been provided requires a thorough analysis. A decision will be made in the coming weeks," said Bélair.

Komie Hossini, communications business partner for crop science at Bayer, which now owns Monsanto, said the company has an “unwavering commitment to sound science and to transparency and has not sought to influence science outcomes in any way.”

Canada's re-approval of glyphosate in 2017 was based on a collaborative effort with the United States to "examine a wide range of environmental and health-related data and information, including hundreds of peer-reviewed, published scientific studies," said Hossini.

"The exhaustive review, which looked at any potential health effects from exposure, among other factors, took seven years to complete and reached the same conclusion as independent regulatory authorities in more than 160 countries, which have approved glyphosate-based herbicides as safe for use."

Hossini also said emails from the company revealed in the Monsanto Papers are "related to secondary review articles sponsored by Monsanto, not original studies or science" and that "the company’s sponsorship of scientific research is disclosed in each article."

Glyphosate-based herbicides, he added, “have been used safely and successfully for over four decades.” There is an "extensive body of research on glyphosate and glyphosate-based herbicides, including more than 800 rigorous registration studies" that confirms these products "are safe when used as directed."

Ross, however, said the 800 studies referred to by the company are about science in general on glyphosate products, and not all specifically related to cancer.

"The lead legal counsel for Lee Johnson has revealed that most of these 800 studies have nothing to do with cancer risk of the pesticide," she said. "In the end there’s about 20 studies that link cancer to glyphosate, and in almost all of these cases it makes a link between glyphosate and cancer."

Cheerios, Kraft Dinner, Ritz crackers and Timbits

As the active ingredient in Monsanto’s multibillion-dollar brand Roundup, glyphosate is used in agriculture, forestry and land management. Over 25 million kilograms of glyphosate-based pesticides are used every year in Canada.

Farmers spray glyphosate on genetically modified crops to get rid of weeds, or to boost the harvest late in the growing season. The chemical is also used in forestry to kill undergrowth, and in land management to kill growth that could crowd out roadways or train tracks.

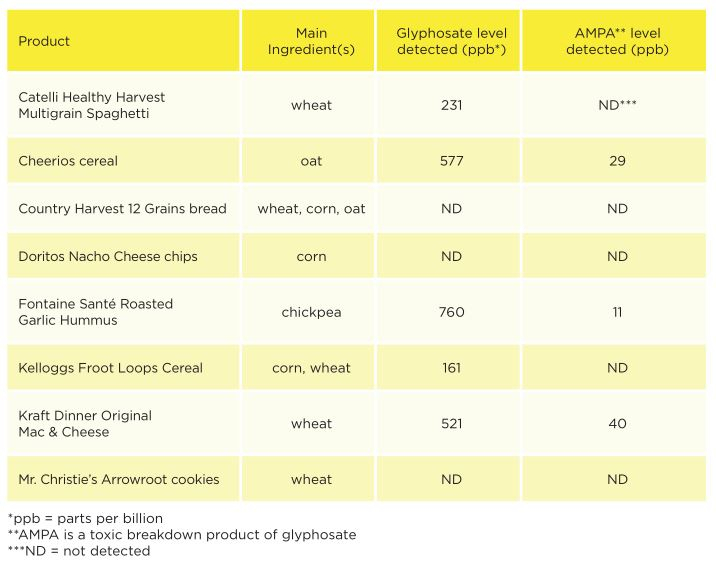

Tests reveal that it shows up in low amounts in some foods Canadians eat. Équiterre and Environmental Defence undertook a joint report showing that glyphosate appears in common foods like Cheerios (577 parts per billion), Kraft Dinner (521 parts per billion), Ritz crackers (569 parts per billion) and chocolate glazed Timbits (209 parts per billion).

Industry argues this represents an extremely low amount of exposure: 500 parts per billion is 0.00005 per cent, for example. Cereals Canada and Food & Consumer Products of Canada have both responded in media reports saying the glyphosate levels noted were at insignificant levels and below safety requirements.

Still, since 2015 glyphosate’s health effects have been under increasing scrutiny around the world. That year, the World Health Organization's International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) decided it was "probably carcinogenic to humans.”

That decision has proved controversial: a “co-analysis” in 2016 with the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation found that the chemical was “unlikely to pose a carcinogenic risk to humans from exposure through the diet.”

Bayer has also said that the IARC opinion is “inconsistent with 40 years of scientific research on glyphosate” and pointed to other regulators who have reached contrary conclusions.

But IARC has continued to defend its findings in the face of what it has called “unprecedented, coordinated efforts" to undermine its work, that it said were coming primarily from "the agro-chemical industry and associated media outlets."

One of the regulators who reached a different conclusion was Canada’s PMRA, which has argued that the IARC made a "hazard classification" and not a risk assessment about "the level of human exposure." In Canada, pesticides are registered for use if the level of exposure does not cause harmful effects.

But the IARC has said it never hid the difference between identifying a hazard and a health risk. "In fact, identifying carcinogenic hazards is a crucially important and necessary first step in risk assessment and management; it should be a 'red flag' to those charged with protecting public health," it wrote.

Canada said it "conducted a rigorous scientific re-evaluation” before coming to its conclusion to re-approve the chemical for sale and use in 2017, saying it is “unlikely to pose a human cancer risk.”

That was after 68 serious incidents alleging a link between glyphosate and cancer were submitted to PMRA between April and October 2016, according to a departmental report. Almost all of these reports came from Monsanto itself, according to Eric Morrissette, chief of media relations at Health Canada. Monsanto is required under Canadian regulations to pass on this information to the department.

Morrissette said all 68 incidents "were assessed as having insufficient information" and that without details surrounding exposure, timing and the onset of symptoms, "a determination as to whether the effects were related to pesticide exposure could not be made." Personal information is also not collected, he said, so "it is not possible to obtain more information from the reporter directly to further evaluate the incident."

These kinds of personal details, in fact, are "frequently not provided to the manufacturer," added André Gagnon, communications advisor at Health Canada. He said "with respect to privacy, personal information is typically removed from the reports before they are submitted to Health Canada to ensure the privacy of the individual.”

European approval far shorter than usual

Concern continues to abound. While Europe approved glyphosate last year, it was for a five-year period, far shorter than the 15-year timeframe that the European Commission usually proposes, and that Canada also uses.

"Glyphosate is no routine case," the commission stated. The commission's decision to reduce the length of the renewal helped ensure a wider support from member states, it said.

Vytenis Andriukaitis, EU commissioner for health and food safety, responded last December to significant concerns from European citizens including a petition by 1.3 million people calling for a ban. He said EU member states must assume responsibility when it comes to the authorization of pesticides.

"They must also ensure that pesticides are used sustainably and in full compliance with label requirements. Transparency, independence, and sustainable use of pesticides are our objectives," he said.

Germany, for example, now wants an "end date" for the use of weed killers that have glyphosate in them, German environment minister Svenja Schulze said this month.

Meanwhile, at the end of October, Bayer faced lawsuits from 9,300 plaintiffs who claim Roundup weed killers made them sick, and that the company knew or should have known of the risks, according to a Wall Street Journal report.

The wave of Roundup lawsuits started after the 2015 IARC classification, the newspaper reported, and since the case of Johnson, lawyers have aired ads looking for new plaintiffs.

The California jury said Monsanto's products had "potential risks that were known or knowable," that the products presented a "substantial danger," the company failed to warn about them even though a "reasonable manufacturer" should have. A judge upheld that ruling last month, although the penalty to Monsanto was reduced.

Équiterre suspects influence over Canada

Équiterre and Environmental Defence, along with advocacy groups Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, Prevent Cancer Now and the David Suzuki Foundation sent a letter Aug. 24, 2017 to then-Health Minister Jane Philpott protesting that the evaluation was “deeply flawed” and providing 58 pages of scientific evidence.

“We raised multiple issues — for instance, Health Canada failed to consider certain evidence on certain risks, or dismissed other pieces of evidence that we thought were quite critical,” said Ross. “Within that, we raised concerns about the evaluation of their cancer risk assessment as well.”

Wisner, Johnson's attorney who presented the internal Monsanto emails, said the company "has specifically gone out of its way to bully" and to "fight independent researchers.” He argued the company wouldn't accept expert warnings while it pursued a goal of writing analyses of their products that was favourable.

Équiterre, which said they have yet to hear a response 16 months after from their complaint to Health Canada, sent another letter Oct. 29 alongside Ecojustice and the earlier coalition to Petitpas Taylor, urging the minister to establish an “independent review panel” to vet the science behind glyphosate’s approval in Canada.

“The troubling conduct by Monsanto exposed in the California litigation appears to have influenced Canada’s glyphosate re-evaluation process,” they wrote.

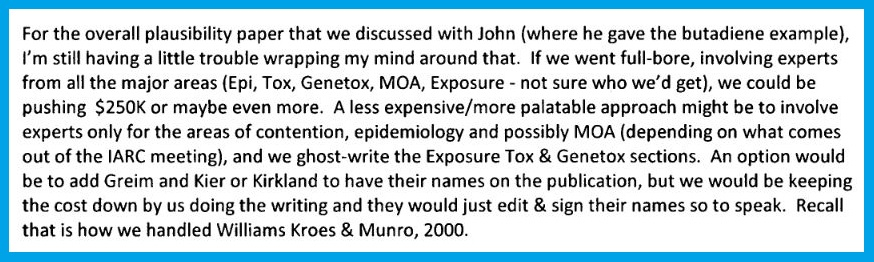

One example is a manuscript for a 2013 genotoxicity review study that appears to have been co-written by a Monsanto scientist, although his name was not included on the study. That study is referred to in a footnote of the re-evaluation decision for Canada, the coalition said.

In an email exposed in the Monsanto Papers, a company scientist can be seen discussing "keeping the cost down by us doing the writing" and that the authors of the study "would just edit and sign their names so to speak." In another part, the scientist suggests they "ghost-write" some sections.

Bayer has pointed in response to a European Food Safety Authority statement that this paper states the authors were paid by a task force to carry out the review, and that “Monsanto facilitated the authors’ work,” so there should be “no illusion about the links between the study authors and the companies that funded or facilitated their work when the experts carried out the risk assessment.”

In at least one case, a scientific journal has published an "expression of concern" that some of its publications did not have all the named contributors.

"We have not received an adequate explanation as to why the necessary level of transparency was not met on first submission," reads the statement by the editor-in-chief and publisher of Critical Reviews in Toxicology.

"When reading the articles, we recommend that readers take this context into account."

Editor's Note: This story is part of a series exploring the pros and cons of pesticide use in Canada, the strengths and weaknesses of its regulatory landscape and who exercises the greatest influence on this landscape. It is being produced in collaboration with The Echo Foundation. National Observer retains full editorial control.

Health Canada dismisses all

Health Canada dismisses all kinds of reports of adverse health effects that are shared with them.

They show over and over again that industry profits are more important than citizen health.

From Roundup to seatbelts in

From Roundup to seatbelts in buses to fracking effects on health and environment, we clearly are not protected by our Federal or Provincial health authorities.

I have always been somewhat

I have always been somewhat suspicious of the chemical industry ever since their smiley faced motto of "better living through chemistry" was plastered around the world.

(To be fair, I have not seen it in recent years....)

I suppose my scepticism was, like that of so many other people, sparked by Rachel Carson and "Silent Spring". I suppose most people under 40 have lost sight of her work. It should be required reading in every chemistry curriculum throughout the globe.

Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma is an ugly form of Cancer. It involves the body's own immune system going haywire - being killed intimately by your own defense force betraying you.

My husband died of it in 1979 and as best we can figure it was his employment by AECL, as a summer labourer while still a teenager, doing clean-up of heavy water spills. His protection consisted of a white jump suit and a badge that measured his exposure to nuclear radiation. The disease was not diagnosed until he was in his early thirties and it had progressed to stage 3 level. From the diagnosis he was told it was incurable - the best Princess Margare'ts oncology dept. could do was to stave off the inevitable - by further poisoning him in the effort to knock back the cancer.

He fought it for 9 years but, as predicted it ultimately overhwelmed him.

No one should have to endure this torment caused by chemical industry ignorance, arrogance and greed. But hundreds and thousands do, and have done now for centuries. Modern chemists are slightly more sophisticated than their alchemical forebears, but no less impressed by their own apparent omniscience. An unbiased viewpoint might conclude that chemists have, over their history, spawned a holocaust that rivals any historical genocide.

Apart from the link with

Apart from the link with cancer, glyphosate also has devastating effects on insects and hence on birds. Herbicides are far more harmful than insecticides because exposed insects fly away and die later, spreading the contamination in a wider circle.

Henri Goulet at Agriculture Canada has found undeniable proof of the difference Roundup makes. Ref.: .

Bottom line, Monsanto wouldn

Bottom line, Monsanto wouldn't have to fake up the science if the science was already saying what they wanted. Clearly the stuff is dangerous.

Pretty much the same goes for GM foods, not that it matters much because by volume most of the GM foods in use are just "Roundup Ready" varieties, which means their main feature is you're supposed to dump more glyphosate on 'em.

Comments