The world’s scientists are urging countries to harness Indigenous knowledge and deploy more renewable energy technology after concluding that carbon pollution levels are leading to unprecedented sea-level rise and loss of glaciers, ice sheets and permafrost.

The latest study by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is the most comprehensive to date of the current and future impacts of the climate crisis on Earth's oceans and the cryosphere, or the parts of the planet that are covered in ice. It represents the work of 104 scientists from 36 countries and draws on 7,000 publications.

The report concludes that ice will continue to disappear and sea levels will continue to rise at staggering rates — even if the international community is able to limit the pollution created by the burning of fossil fuels and their products, like coal, gasoline and natural gas, and limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

The shrinking cryosphere has led to “predominantly negative impacts” on people’s “livelihoods” and their “health and well-being,” the report reads, affecting everything from food and water availability to infrastructure, business and the “culture of human societies,” especially for Indigenous Peoples.

Scientists say there are solutions to address this crisis — but only if the global community acts urgently and adopts the knowledge and capabilities of those who will be most affected by climate change. “Adaptation efforts have benefited from the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge and local knowledge,” it states.

But time is of the essence. The world's oceans have already absorbed “more than 90 per cent of the excess heat in the climate system," and since 1993, the rate of ocean warming has more than doubled, reads the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC).

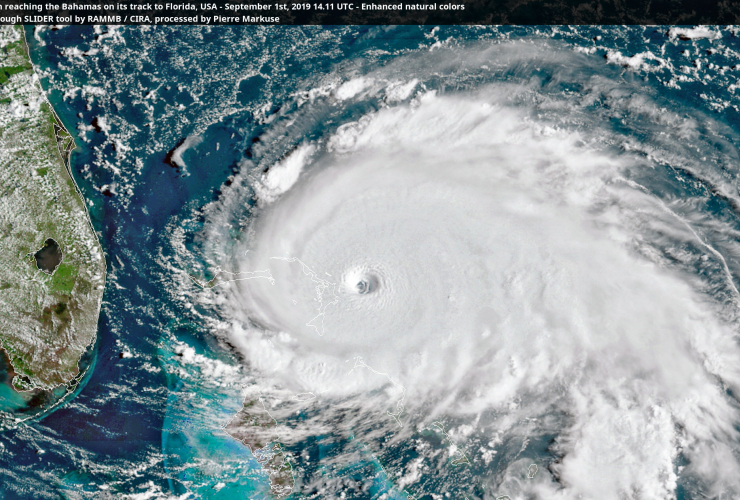

Rising ocean temperatures means more intense tropical cyclones, with more powerful storm surges and downpours, leading to more extreme weather along the coasts and potentially devastating loss of marine ecosystems.

“If we reduce emissions sharply, consequences for people and their livelihoods will still be challenging, but potentially more manageable for those who are most vulnerable,” Hoesung Lee, chairman of the IPCC, said in a statement.

One-quarter of North’s permafrost in danger

The Earth’s population depends on the global ocean, covering almost three-quarters of the planet’s surface and containing almost all of the Earth’s water. Around a tenth of Earth’s land area is covered by glaciers or ice sheets. All of these ecosystems are deeply threatened by global heating, the IPCC’s new report finds.

“The open sea, the Arctic, the Antarctic and the high mountains may seem far away to many people,” said Lee. “But we depend on them and are influenced by them directly and indirectly in many ways — for weather and climate, for food and water, for energy, trade, transport, recreation and tourism, for health and well-being, for culture and identity.”

The picture the SROCC report paints is extremely dire, and will deeply affect the roughly 650 million people living in low-lying coastal areas, as well as the four million people who live in the Arctic region permanently, including 400,000 Indigenous Peoples.

Under a business-as-usual scenario, the scientists say, a huge portion of Europe, Asia, the Andes, Mexico, eastern Africa and southeast Asia will lose over four-fifths of their current ice mass by the end of the century.

And, worryingly for Canada — where permafrost cover accounts for some 40 to 50 per cent of land — “widespread permafrost thaw is projected for this century and beyond,” the report states.

"If greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase strongly, there is a potential that around 70 per cent near-surface permafrost could be lost.”

The SROCC report is the fourth in a series of UN reports on the effects of the climate crisis. It follows a new UN science report released Sunday that shows emissions continue to surge, while G20 countries responsible for 80 per cent of global carbon pollution are failing to meet their already-low targets.

Countries overall must triple their 2015 pledges to keep global warming well below 2 C by 2100, or increase them fivefold to hold it to 1.5 C, that report indicated — a threshold seen as critical to the survival of small, low-lying countries and islands, who are already on battling the worst of the climate crisis.

The SROCC also follows another sobering report released by the IPCC last month that warned of the devastation caused by rising global temperatures and raised concerns about the world's ability to provide sufficient food for humanity as crop yields decrease and droughts and wildfires become increasingly common.

🌊#IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate

— IPCC (@IPCC_CH) September 25, 2019

Our Ocean and Cryosphere - They sustain us. They are under pressure. Their changes affect all our lives. The time for action is now.#SROCC PR ➡️ https://t.co/HrSmr14Cu5

SPM ➡️ https://t.co/Zq29IY9KxX pic.twitter.com/hC3KHOmAv8

If humans don’t begin slashing their pollution, hundreds of billions of tons of carbon and methane locked under permafrost will be released into the atmosphere, rapidly accelerating climate change. At least one-quarter of the northern hemisphere's surface permafrost could melt by the end of the 21st century.

The unprecedented rate of ocean warming has also reduced the supply of oxygen and nutrients for marine life, forcing a rapid decline in fish stocks that could disrupt the food chain. Meanwhile, Arctic sea ice is getting thinner every month of the year.

Extreme sea levels that are usually experienced once every 100 years will occur at least annually by 2050 for many low-lying cities and small islands, IPCC’s scientists said. That could displace hundreds of millions of people.

The fundamentally unfair nature of the climate crisis — that those with the least amount of resources to defend themselves against climate change are also the ones most threatened — is laid bare by the scientists in the report.

“People with highest exposure and vulnerability to current and future hazards from ocean and cryosphere changes are often also those with lowest adaptive capacity, particularly in low-lying islands and coasts, Arctic and high mountain regions with development challenges,” reads the report.

There are significant financial and technological barriers to implementing responses to future impacts of climate change in order to reduce the risk of impacts, it noted. And communities in coral reef environments and atolls, as well as low-lying Arctic locations, are at risk even if they move to adapt themselves as conditions will approach intolerable.

The scientists admitted it was difficult to project perfectly accurately when humans would desert specific locations entirely due to conditions being too harsh. But they assessed, with medium confidence, that “some island nations are likely to become uninhabitable due to climate- related ocean and cryosphere change.”

Pollution cuts urgently needed to preserve oceans

The report finds strongly reducing greenhouse gas emissions, protecting and restoring ecosystems and carefully managing the use of natural resources would make it possible to preserve the ocean and cryosphere.

Cutting carbon pollution now will help reduce the severity of climate change in the future, the scientists said: “Strong reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in the coming decades are projected to reduce further changes after 2050.”

Restoring carbon sinks like mangroves and tidal marshes can also help store around 0.5 per cent of current global emissions every year.

Renewable energy technologies can be deployed in the ocean, that can extract excess energy from the Earth's water system through wind, tides, waves, thermal and saline and algal biofuels.

But the scientists make it clear that responding to this challenge presents society with major challenges, due to the “uncertainty about the magnitude and rate of future sea-level rise” as well as “vexing trade-offs” that must be made on values like safety and economic development.

“These challenges can be eased using locally appropriate combinations of decision analysis, land-use planning, public participation, diverse knowledge systems and conflict resolution approaches that are adjusted over time as circumstances change."

Governments need to co-operate and co-ordinate "across scales, jurisdictions, sectors, policy domains and planning horizons" to prepare for these growing changes in the ocean and cryosphere and sea-level rises.

There also needs to be growing promotion of climate literacy and an understanding of local, Indigenous and scientific knowledge systems in the public awareness. The report finds that managing ecosystems are “most successful” when they are supported by communities, based on science and incorporate “local knowledge and Indigenous knowledge.”

Comments