Ron Lemaire is a “produce guy,” but COVID-19 educated him in milk and meat.

That’s because since March, the president of the Canadian Produce Marketing Association has joined forces with eight other non-profits. Together, they laid the groundwork to move millions of kilograms of surplus food from producers to hungry Canadians.

Their plans will soon go live thanks to the $50-million federal Surplus Food Rescue Program, details of which were announced Thursday by Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food Marie-Claude Bibeau.

“The benefit of getting the $50 million from the federal government is one thing,” Lemaire said. “The challenge will be to move food into the communities that need it.”

Statistics Canada reported in June that one in seven Canadians (14.5 per cent) didn’t have enough food during the previous month — a four per cent increase from data collected in 2018.

About 19 per cent of Canadian households with children reported lacking food in May. And Canadians absent from work due to the pandemic were about three times as likely to be food insecure compared to those who kept working.

The funding will support distribution networks established by national food charities and organizations, including Food Banks Canada, Second Harvest, and the Canadian Produce Marketing Association, to better reach those in need.

These three organizations will receive more than $11 million each to move food from producers to local food banks and food charities across the country.

It’s an unprecedented boost for efforts the organizations have been working on for years.

“It’s significant, the waste that we see, the amount of food that never gets eaten,” said Lemaire.

The pandemic has made the waste problem worse — most hotels and restaurants were forced to close in March, stranding about 5.8 million kilograms of food — but Canada’s food system was already wasteful.

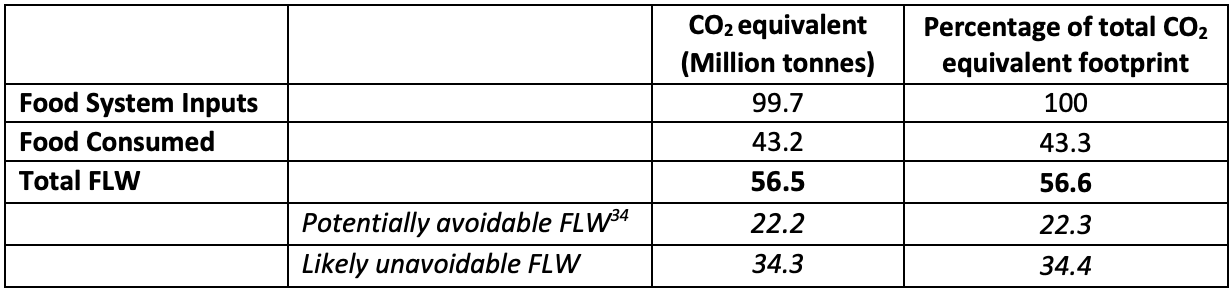

A 2019 report by Second Harvest found that about 35.5 billion kilograms of food is wasted in Canada annually.

Of that loss, 32 per cent — worth $49.5 billion — is edible and could be avoided.

“This problem is not just a pandemic problem,” said Tammara Soma, a professor of resource and environmental management at Simon Fraser University and an expert in food waste. “We have a system where we are constantly overproducing, even before the pandemic.”

That means, while the Surplus Food Rescue Program is important to deal with an immediate problem for farmers and people without enough food, it only makes sense as part of a long-term strategy to invest in infrastructure that will help reduce food waste, increase communities’ resilience, and get food to hungry Canadians for years to come.

Some of this infrastructure used to exist in Canada, but has vanished in the past several decades. For instance, B.C. lost most of its processing facilities in the 1990s after NAFTA made it easier for Canadian produce, meat, and fish to be exported for processing at plants in the United States, where labour is cheaper.

Not only did this make the province’s supply chains longer, it encouraged farmers to grow one or two crops in large quantities for distribution across Canada and beyond — or to be wasted if market conditions changed and their crops were stranded.

Almost two-thirds of food in Canada is wasted before it reaches store shelves, noted Second Harvest’s 2019 report.

Meanwhile, Soma explained, British Columbians started to rely on imported foods that are more vulnerable to disruptions like COVID-19 or climate change.

Investing in local processing capacity, increasing supports for farmers, so they can grow more diverse crops that are better adapted to local needs, and helping food banks and charities increase their storage capacity should all be considered as Canada looks to reduce food waste and hunger, she said.

“We need to be very strategic with this because moving perishable food around without a proper long-term strategy is not going to solve the waste issue and is not going to solve the food security issue.”

It's also relies heavily on fossil fuels, she noted.

Ensuring the gains made through the program aren’t lost is also top of mind for Lemire. In fact, it is one of the best parts of the federal initiative, he said.

“This enables us to create a legacy plan where, even if there are no federal monies, the connections that are being created between food and charities is fundamental. They existed in the past, but now they’re much more structured and uniform,” Lemire said. That means future surpluses, COVID-19 related or not, will be distributed more efficiently across the country.

Still, that might not be enough to really eliminate food insecurity, according to Graham Riches, a professor emeritus of social work at UBC whose research focused on hunger.

He noted that the first food banks and food charities appeared in Canada during a recession in the 1980s, and modelled an American approach to reducing hunger. That approach focused on food corporations redirecting surplus food to, and funding, food banks and charities — not increasing people’s incomes enough that they could afford to buy their own food.

Focusing on redistribution instead of income doesn’t really solve the problem, Riches said. Hungry people remain without the means to feed themselves, while food donations have a relatively minimal impact on reducing food waste — in Canada, only about 0.1 per cent of food wasted after harvest and processing is recovered in Canada, he noted.

Lori Nikkel, the CEO of Second Harvest, agreed.

“Food security has nothing to do with food,” she said. “Food security is about income. Only when you can buy your own food will you be food secure.”

Fixing the systemic failures underpinning hunger in Canada and B.C. is more complex than a $50-million program can allow, she said. They’re challenges that existed before the pandemic. She hopes they won’t be as prevalent in the new normal that follows COVID-19 — a hope she's seen grow since the government's increased interest in the problem during the pandemic.

Still, she's delighted by the funding.

“This isn’t going to solve food insecurity, but it’s going to help support people with food right now.”

Marc Fawcett-Atkinson/Local Journalism Initiative/Canada's National Observer

Comments