A statistic that often circles J.B. MacKinnon’s mind is a shocking one: If everyone consumed at the same rate as the average American, we’d need more than five planets to sustain us.

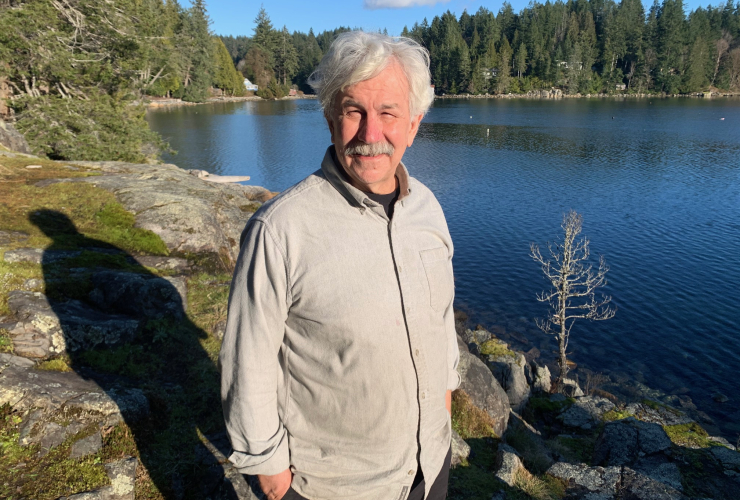

The Vancouver-based author, known for his book The 100-Mile Diet, said it’s a piece of research that is often parroted. However, he says the flip side needs more attention. It’s why he applied that thinking while writing his new release, The Day the World Stops Shopping, which explores what would happen if we dramatically altered our consumption habits.

MacKinnon says there are real world examples of countries, such as Ecuador, that are the opposite of America: If everyone consumed like the average citizen, we’d only need one planet.

“I thought I'd go to Ecuador and see what one-planet living looks like on planet Earth right now ... in some ways, it was like being beamed back to the early '70s or the '60s,” he said.

“It wasn't by any means an unlivable set of circumstances. But it was a considerably simpler consumer lifestyle than we know today.”

MacKinnon spoke with Tzeporah Berman, adjunct professor of environmental studies at York University, at a Tuesday event hosted by the Vancouver Public Library about why we shop so much and what could be done to change our habits.

Berman pointed out that it’s a privileged position to be in — coming from Canada and simply saying, ‘People are happier with less stuff,’ but that the crux of the book isn’t so simple. It digs into the psychology of materialism and the way our government and corporations back us into a corner of overconsumption.

MacKinnon said parts of the book explore the difference between extrinsic and intrinsic values. Meaning, things that make us happy from approval outside ourselves (such as a new outfit), and others that rely on approval from within ourselves.

“It's not that we're not interested in having close relationships with people we care about, or spending time in nature or some of these other intrinsic values,” he said.

“We just happen to live in cultures that don't make a lot of time, don't allow us a lot of time, for those sorts of values to be expressed. That's not how our culture is structured.”

This emphasis on extrinsic values and the earn-and-spend cycle that our society gets wrapped up in are partly to blame for overconsumption. As MacKinnon reached the end of writing the book, the pandemic hit, which put questions about intrinsic and extrinsic values to the test. Mainly, if we shut off access to consumption, will people shift gears and start embracing their intrinsic values more?

This happened at first, he said, when people flocked towards shelves of yeast to start making bread and invested ample time in connecting with their friends and family over Zoom. But eventually, after a sharp dip in consumption, things quickly climbed back up.

“During the pandemic, across the whole arc of the pandemic — services went down, product went up. We as a consumer society, that's what we're used to doing,” he said.

“We found new ways to do it — a lot of consumption went online. Rather than consuming some of the products and services we normally would, we consumed enormous amounts of viewable material online, we streamed like crazy.”

MacKinnon says it’s hard for us to turn our backs on materialism. It’s why baking bread, at first an intrinsic activity, turned into an extrinsic expression. Social media became covered in pictures of perfectly risen loafs; it was a competition.

He says a shift needs to occur: from us being consumers, to us being participants. An organization called Participatory City, which has projects in Toronto, Halifax and Montreal, has a pilot project outside of London that MacKinnon said was one of the most moving things he saw while researching his book.

In Barking and Dagenham, the group set up what MacKinnon called the "largest experiment in the world right now." People are provided with activities and workshops that give them something to do other than consume.

“So any day that you wake up in Barking and Dagenham, right now you can go down to what they call the shops. And there will be things going on that you can do for free with your neighbours,” he said.

“And it builds the possibility of a completely different social role ... it offers this role of 'I'm going to get up, and I'm going to do things with my neighbours and in my neighbourhood. There's so many options for me, and that's how I'm going to use my time.'”

Of course, individual and community-driven solutions need to be coupled with changes from governing bodies, said MacKinnon. Planned obsolescence, which is where a product is designed to eventually break, has started to be addressed by some governments — France has said that a company can no longer design a product to fail.

He went on to talk about the role of corporations, how we think about economic growth — both of which he explores in his book.

Ultimately, MacKinnon says, all these parts could make a shift towards a more just and desirable society and planet.

“We simply cannot continue to consume more and more and more, every single citizen on the planet,” he said.

“It just makes the challenges in terms of dealing with ecological crises just far too high.”

Entitled to his opinion,

Entitled to his opinion, harmless, might do some good. What an enemy for the fashion industry! You'd have to close half of retail if we went back to owning a couple of outfits each, before homes had 'closets', because nearly all clothes would fit in an armoire.

But "consumption" is a matter of serious study for peer-reviewed economists, and it's probably better to read their work to really understand the issue. Dr. Robert Frank of Cornell has devoted a career to it, and his mass-market books "Luxury Fever", and "The Darwin Economy" are fun, and highly clarifying.

With many examples, he shows the need to show status by having admired possessions is a universal across all cultures and centuries; so is taking that to higher and higher levels if wealth is available and competition for mates and status is strong. It absolutely predates advertising. (Certainly, the explosion in clothes-buying started in the mid-19th century, when automation made clothes far more affordable. Radio and TV were not invented.) Dr. Frank has some economics-based prescriptions to "nudge" people into less consumption for pure status reasons.

Consumption is so much more than individual purchases of medium-sized dry goods, online or not. It's whether you live in an 600 sf house like my mother in the 1930s, or the 1600 sf house we moved into 35 years later, with 3 teenagers. It's the burbs vs condos, it's "The two car family" being an aspiration in the 1960s. It's the human race making 1 billion tonnes of steel per year, and another billion of concrete, because Asians don't want to live in huts any more.

There's a conflict there with the Green New Deal, which needs to be global, and will involve the manufacture of several hundred million electric vehicles, several hundred thousand multi-megawatt wind turbines, and a good hundred million tonnes of solar panels.

All that (crankily) said, consuming medium-sized dry goods as a dopamine-making habit is a real Thing. Mostly, I'm thinking fashion, what people usually are talking about when they say "retail therapy"; few cheer themselves up by shopping for aluminum siding. Addressing that mental health issue really would be a good idea.

What was odd to me, is that

What was odd to me, is that the article claimed that sustainable looked like a place that looked like here in the 1960s and 1970s. I'm pretty sure I first heard the "we need X Earths" comment back in those decades!

I think the comment arises from the assumption that the current Earth economic output is the maximum possible, and that if more of the population consumed more, it would be impossible with Only One Earth. Sure enough, the globe is now producing almost exactly five times as much steel per year as in 1960.

Four more planets? No Problem

Four more planets? No Problem -- http://youtu.be/BiswXRIK80k

Comments