As part of a series highlighting the work of young people in addressing the climate crisis, writer Patricia Lane interviews Erin Moir, an outdoor educator who believes forests can help heal us.

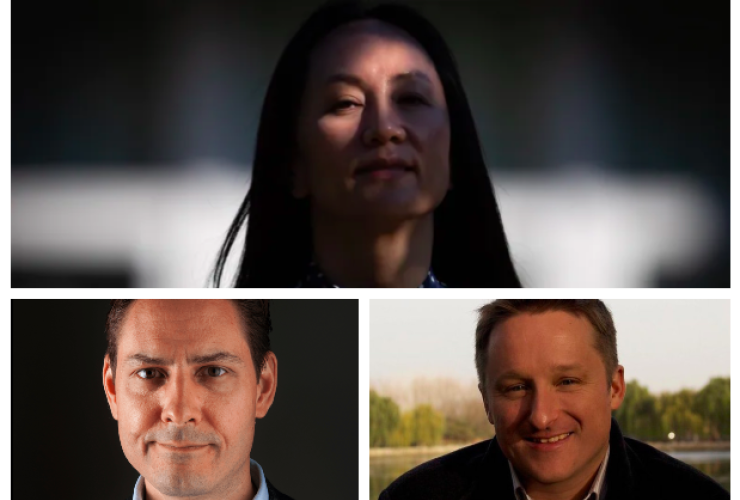

Erin Moir

Outdoor educator and science enthusiast Erin Moir believes forests can be our therapy. As part of her work as education director with Thunder Bay’s EcoSuperior environmental programs, she is training to become a certified forest therapy guide.

Tell us about forest therapy.

When we walk or hike through a forest, we often feel better. Science tells us trees emit chemicals that absorb air pollutants and make us feel good. A guided forest therapy walk invites us to be less cerebral and more mindful about the emotional experience that is so often available if we are open to it. Also known as forest bathing and shinrin-yoku, forest therapy can be a gateway practice into “re-wilding” ourselves — nourishing us as we renew our connection with the living landscape.

You have spent your career as an outdoor educator. Is this a surprising turn?

While seeing forests or wild spaces as offering a therapeutic encounter is a recent development in North America, it has been practised in places like Japan for a very long time. Indigenous people all over the world have always had a relationship with their lands. Science proves spending time in nature reduces stress by lowering our blood pressure, pulse rate, and cortisol levels, improves and stabilizes our mood, boosts immunity, and improves concentration, sleep and self-esteem and creates an enhanced sense of belonging. Some Canadian physicians now prescribe time in nature to support better mental health.

What is the difference between a nature hike and guided forest therapy?

I still love taking the public out to learn the names of flowers or plants, and I like taking my family on hikes. But when we guide a forest therapy walk, we invite people to simply be in nature without any other agenda. When we allow ourselves to be fully present to the sights, sounds, smells, tastes and feelings of nature, we become attentive to parts of ourselves that might go otherwise unnoticed. People are often made aware of emotions or thoughts that were not obvious to them. We might feel unusually at home. We might experience leaning on a tree that asks nothing in return as a beneficial and unusual experience. In return, we often feel grateful. A relationship is established that is about so much more than seeing trees as sources of scientific inquiry or timber. It is one thing to put our bodies or prefrontal cortex in nature, and quite another to allow our minds simply to be present with no other goal.

Do you think forest therapy has a larger role to play in conservation?

I don't think it is a coincidence that Japan has one of the highest concentrations of old forests in the world and venerates old trees. Forest bathing is accepted there. People feel part of the natural world, and destroying it is an anathema to them. We have to preserve forests because they are such good carbon sinks and offer such diversity. People are much more likely to protect what they know and what they feel is part of them.

How did your background prepare you for this?

My dad is a wildlife ecologist and I grew up as a free-range kid on a large property exploring woods, and creeks. Becoming an outdoor educator was a natural next step. My director at EcoSuperior trained as a forest therapy guide, and she encouraged me to do so, too. Part of the training is to pick a single place in nature and sit there for a period of time many times a week for six months or longer. This has changed my relationship to that place. The idea that I am separate from nature is increasingly foreign to me as I become more accepted by the wild things that make their home there. I am learning to see their habits and behaviours as communication, just as I see human habits and behaviours as attempts at connection. I feel actively welcomed by the beings who live there.

What keeps you awake?

I am fortunate to have had a childhood connected to nature. I have young children and I worry climate breakdown may mean they or their children may not have that opportunity.

What gives you hope?

I love my job. I get to see people deepening their connection to nature and all the wonder and excitement that brings.

What advice do you have for young people?

Stay open. I thought I was doing my job well before I began this work. Now I can see a whole new dimension. You never know what is around the next corner.

What would you like to say to older readers?

If young people ask for help, listen and trust that their ideas are valuable and worth supporting. And try new things yourself. I was nervous when I started this practice. It has been so rewarding to just begin.

Did not know such a

Did not know such a discipline existed. Have, however, always felt a healing kinship with trees and the forest. I experience a great discomfort at the sight of treeless housing/living areas. It breaks my heart to hear of the destruction of old growth forests in favour of "development" - not only the Japanese consider this an abomination.

Comments