This story was originally published by The Guardian and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The prospect of harnessing the power of the stars has moved a step closer to reality after scientists set a new record for the amount of energy released in a sustained fusion reaction.

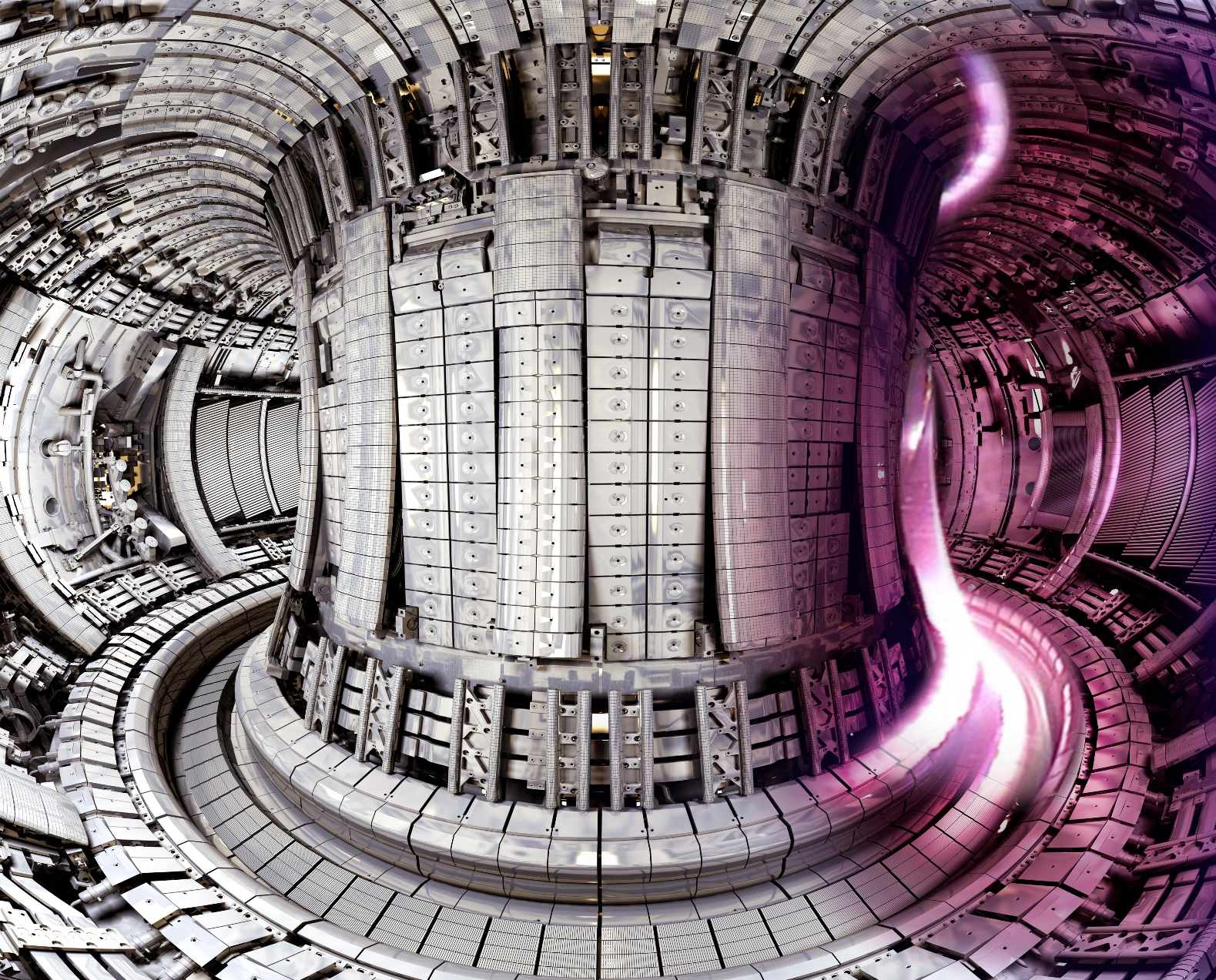

Researchers at the Joint European Torus (JET), a fusion experiment in Oxfordshire, generated 59 megajoules of heat — equivalent to about 14 kilograms of TNT — during a five-second burst of fusion, more than doubling the previous record of 21.7 megajoules set in 1997 by the same facility.

The feat announced on Wednesday follows more than two decades of tests and refinements at the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy and has been hailed as a “major milestone” on the road to fusion becoming a viable and sustainable low-carbon energy source.

Landmark results from EUROfusion scientists at UKAEA’s JET facility.

“These landmark results have taken us a huge step closer to conquering one of the biggest scientific and engineering challenges of them all,” said Prof. Ian Chapman, the chief executive of the UK Atomic Energy Authority. “It’s clear we must make significant changes to address the effects of climate change, and fusion offers so much potential.”

The doughnut-shaped JET is built to contain plasmas, or highly ionized gases, which are heated to 150 million degrees Celsius, 10 times hotter than the centre of the sun.

At such extreme temperatures, atomic nuclei can fuse together to form new elements and release vast amounts of energy. The same fusion reactions power the sun, but at considerably lower temperatures, because stars have gravity to lend a hand.

Experiments at JET have focused on whether fusion is feasible with a fuel based on two isotopes of hydrogen known as deuterium and tritium, which combine to form helium gas. The latest results suggest that it is and provide crucial confirmation for Iter, a larger fusion project being built in the south of France. Iter is scheduled to start burning deuterium-tritium fuel in 2035 and ultimately generate more heat than is needed to keep its plasma at high temperature.

If all goes well with Iter, the next step is to build a European demonstration power plant that produces more electricity than it uses and is hooked up to the grid. The prospect of fusion energy is deeply attractive because it does not release greenhouse gases and one kilogram of fusion fuel contains about 10 million times as much energy as one kilogram of coal, oil or gas.

While deuterium is abundantly available in seawater, tritium is extremely rare and produced in nuclear reactors. Future fusion plants — Iter included — are expected to make their own tritium fuel by using high-energy neutrons, released when deuterium and tritium fuse, to split the common metal lithium into tritium and helium.

Dr. Mark Wenman, a reader in nuclear materials at Imperial College London, said that while the experiment released fusion energy for only five seconds, it proved that the fuel could be burned in a sustainable manner. “It’s been a while since they have produced a record like this and it’s a major milestone on the way to proving that fusion’s a viable and sustainable energy source for the future.

“Five seconds doesn’t sound like much, but if you can burn it for five seconds, presumably you could keep it stable and keep it burning for many minutes, hours, or days, which is what you are going to need for a proper fusion power plant. It’s the proof of that concept that they have achieved,” he said.

Prof. Ian Fells, the emeritus professor of energy conversion at the University of Newcastle, said the record-breaking release of fusion energy was “a landmark” in fusion research.

“Now it is up to the engineers to translate this into carbon-free electricity and mitigate the problem of climate change,” he added.

That's enough power to run a

That's enough power to run a plug-in baseboard heater for almost half a day, whicht costs less than four dollars in my area. Meanwhile, the experiments are running into multi-million dollar sums. These folks are not going to save us from global warming; they are just trying to be amazing and stay employed. The Achille's heel of Fusion is that we have to use neutron-enriched fuel to have any hope of success, and that will then turn the facility into radioactive waste. We have the sun at a nice, safe distance providing fusion power now.

The joke goes that practical

The joke goes that practical fusion power is just 30 years away . . . and always will be. I'm fine with funding the research, because it's cool and probably ends up telling us a bunch of good physics stuff which will either be useful in other ways or will just be, I dunno, a nice part of civilization's scientific knowledge.

But we shouldn't delude ourselves that it's gonna save us from climate change. Or that once it can be made to work, like maybe in 2080 or something, it will somehow be this totally perfect power source. Fission was going to be "too cheap to meter" and look how that worked out.

Aww Cmawnnnn. Y'er no more

Aww Cmawnnnn. Y'er no more fun for the radiation industry people, than solar sound panels on every rooftop would be for the petro people.

And no wonder who-was-it wants to buy up mining rights for all the lithium deposits he can find ...

(Maybe the countries involved could figure out how to deploy less costly and already known technologies; there's plenty of time to play with unlikely physics once no one's starving,)

(And I'll bet taxpayers are funding the whole schlmozzle, too ...)

What a bunch of cynics! Did

What a bunch of cynics! Did you stop to think of how many years and billions of publicly funded research went into solar panels and the electronics that make them possible?

So 'fusion power' will not save us from climate change because it is not won't be ready in time (neither will solar!), but you should do the engineering arithmetic before you write it off: one fusion power source and its construction costs and operating vs. the equivalent acres of solar panels and the industrial and environmental costs of construction, maintenance etc. Please factor in the little know fact that the effective, average solar panel operational efficiency in places like Vancouver is around 10%, even though the maximum efficiency in full sunlight is over 70%. Enjoy the arithmetic!

Comments