On May 31, Cenovus announced it will restart the West White Rose project in the Newfoundland and Labrador offshore. The premier and his energy minister immediately made themselves available to the media to state government support for the restart. The terms of the restart include a revised royalty structure with rates as low as 1.25 per cent when Brent crude is trading at between $65 and $75 a barrel.

Premier Andrew Furey was quick to respond and was quoted as saying, “It’s incumbent, it’s responsible, it’s ethical for us to be picking the lower-carbon emitting products.”

The Newfoundland and Labrador government has long argued its offshore produces lower-carbon oil than other jurisdictions. However, it is worth examining the environmental policies and approaches applied in the province’s offshore industry. Political scientist Angela Carter has documented the problems with environmental policies in the Canadian petro-provinces in her book Fossilized. Carter, a Newfoundlander, says the province's industry was developed in a context of economic precarity and major environmental and financial concessions have been made to ensure the province would have an oil sector.

In the 1970s, in the face of a global energy crisis, exploration in the Newfoundland offshore was considered central to Pierre Trudeau’s energy policy. Euphoria ensued when the first oil discovery came in 1979 with the Hibernia oilfield. Carter maintains the project was heavily subsidized throughout the exploratory phase in the 1980s. She notes the federal government offered $1 billion in grants and $1.7 billion in loan guarantees, in addition to tax concessions. These subsidies were found to be higher than elsewhere in Canada.

Carter also discusses the research of Daria Crisan and Jack Mintz of the University of Calgary School of Public Policy, as well as Mintz and Duanjie Chen. They found that royalty rates in the Newfoundland offshore were significantly lower than rates in Saskatchewan and Alberta. Carter concludes that with an estimated aggregate marginal effective tax rate and royalty rate of 12 per cent, Newfoundland and Labrador’s oil “appeared to be sold at a discount to encourage extraction.”

Carter says the Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board (C-NLOPB) has been under “regulatory capture” (or conflict of interest) because of its close relationship with the oil industry. This means that the board often behaves as an advocate for industry rather than the people of the province who own the resource or the environment they depend on for their survival. Carter points out that this has been noted by representatives of the province’s fishing industry, as well as local communities.

Scientists such as C.M. Burke, W.A. Montevecchi, and F.K. Wiese have raised concerns about the C-NLOPB’s environmental monitoring processes. Scientists maintain that positions put forward by industry are often not supported by scientific research and that research gaps remain on pollution and wildlife in the Newfoundland offshore.

The environmental affairs division of the C-NLOPB is small, even though the environmental assessment process is a key aspect of the board’s mandate. Consultations are often rushed, with limited opportunities for input, and the C-NLOPB is not required to act on concerns raised by the public.

According to Fisheries and Oceans scientists, who do not want to be identified, there is little to no followup to ensure environmental assessment conditions are met. Project operators are required to monitor their own state of compliance.

Carter also found that among Canadian provinces and territories, Newfoundland had “the largest share of emissions originating from large industry.” According to the Environment and Climate Change Canada report on the largest emitting facilities in Canada in 2018, four of the Newfoundland and Labrador offshore oil projects reported carbon dioxide emissions between 333,567 to 551,420 tonnes. North Atlantic Refining was also listed at 1,343,387 tonnes.

It is also noteworthy that one of the worst disasters in the history of the oil industry happened offshore of Newfoundland and Labrador, killing 84 men. In The Ocean Ranger: Remaking the Promise of Oil, Susan Dodd notes that as recently as 2008, former federal minister and Newfoundland MP John Crosbie said, “We still don’t know how to get men off those rigs.”

Working in the North Atlantic continues to be a precarious situation. However, after the Ocean Ranger disaster, a quick return to the Newfoundland offshore was managed through a public inquiry because oil was seen as the province’s path to economic independence.

The International Energy Agency has maintained since 2021 that the world does not need new energy projects. We have enough fossil fuels to get to net-zero by 2050. Environmental Review Letters recently published research that shows 40 per cent of existing fossil fuel projects must be decommissioned early to keep global warming to 1.5 C.

Given that parts of India are already recording days when the surface temperature is above 60 C and the world is in danger of food shortages, perhaps it is time for a better strategy than greenwashing a highly problematic industry.

Why don't you tell us how

Why don't you tell us how many kg of CO2 will be emitted per barrel of White Rose oil produced, and compare it with the oil sands and with Saudi Arabian production? You are making unquantified claims.

The excerpts below from

The excerpts below from recent news and analysis articles give a rough indication:

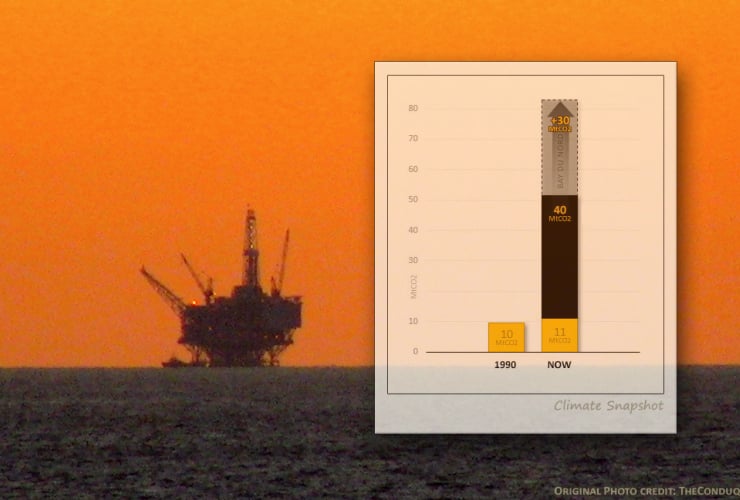

1) "Greenhouse gas emissions from production are anticipated to be as low as eight kilograms per barrel. The average emissions from oil production in Canada is 40 kilograms per barrel, and in the oilsands, it's 80 kilograms."

https://atlantic.ctvnews.ca/n-l-bay-du-nord-oil-project-highlights-tensi...

2) "Scope 3 emissions average 430 kgCO2/barrel"

Federal rule on oil and gas projects ‘does not stand up to the facts’, April 11th 2022

https://www.nationalobserver.com/2022/04/11/news/federal-rule-oil-and-ga...

Average barrel in Canada: 430 + 40 kgCO2 = 470 kgCO2.

Newfoundland's offshore: 430 + 8 kgCO2 = 438 kgCO2.

Oilsands average: 430 + 80 kgCO2 = 510 kgCO2.

Oil from Newfoundland's offshore generates 7% less emissions than the average barrel in Canada and 14% less than the average oilsands barrel.

I don't know about offshore production, but oilsands emissions of all types are grossly under-reported.

That said, no oil is climate friendly. No new O&G projects are needed if we are to keep within the warming limit of 1.5 C (IEA). Expanding oil production is incompatible with Canada's inadequate climate targets.

Rystad Energy: "Among the top

Rystad Energy: "Among the top 10 oil and gas producing countries, Canada had the highest CO2 emission intensity per barrel of oil equivalent."

Canada's average crude carbon intensity is more than twice the global average. Almost double Iran. Nearly triple Russia. More than triple the U.S. Four times Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Five and a half times Norway and the UAE.

"Canada, with an average intensity of 39 kg per boe, has a high share of its production from oil sands, typically emitting three to five times more CO2 per barrel than the global average of 18 kg per boe."

"Rystad Energy calculates that the carbon intensity of the U.S. shale industry's CO2 emissions is about around 12 kg per barrel of oil equivalent. In contrast, the oilsands is calculated "at a staggering 73 kg" per barrel of oil equivalent. Conventional onshore producers such as Saudi Arabia have a footprint of 19 kg per barrel of oil equivalent."

"Four Pipeline Realities for Alberta's Rumpelstiltskin" (The Tyee, 24-Jan-21)

https://thetyee.ca/Analysis/2021/01/24/Alberta-Rumpelstiltskin/

What a failure of media and

What a failure of media and the schools that we don't know these things!

Thank you. This is exactly

Thank you. This is exactly the sort of factual information that would increase the impact (and the quotability) of many National Observer articles.

Informative article.

Informative article.

One comment following from this paragraph:

"In the 1970s, in the face of a global energy crisis, exploration in the Newfoundland offshore was considered central to Pierre Trudeau’s energy policy."

Don't forget Dome Petroleum which was in its heyday as a federal darling at that same time, exploring in the Beaufort; I just don't recall if the exploration was done on the public nickel or with huge write-off ability. I recall the term "super-depletion allowance."

One might say that, to its credit, the gov't of Trudeau père was very actively seeking a workable energy policy to assure Canadians of energy security and stability. One might also say that its strategy was not adored.

Here's an interesting article, which I just found, on Dome from 1984, when the piper was knocking on the door seeking payment.

https://www.nytimes.com/1984/08/19/business/dome-s-fight-to-untangle-a-v...

Still an eye-roll for me to

Still an eye-roll for me to call the tar sands the 'worst' because of several percent higher carbon emitted during extraction - when the whole product is carbon, it's just that few percent. But by that same token, ditto here for industry to call it "low carbon"; it's like the Hell's Angels pointing out they are a much-nicer criminal gang than MS-13.

As to "ethical", come on. These are routine ethical arguments in North America about finance, workers, environmental rules. They don't remotely compare to buying oil from Mohammed bin Salman.

Comments