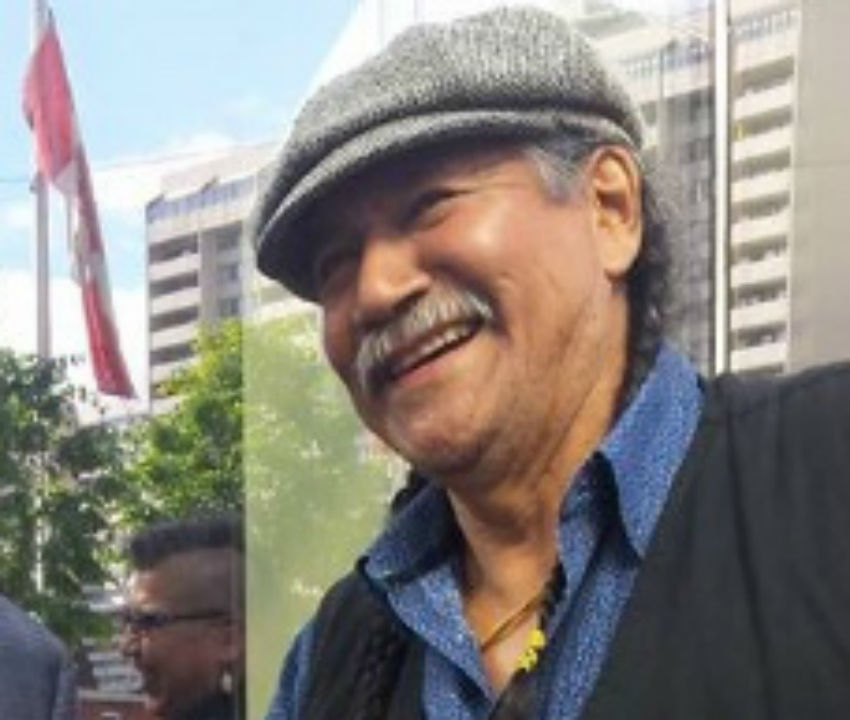

Cree Elder Patrick Etherington recently spent a week at Inuit and Northern Affairs Canada, in Ottawa, educating public servants about his culture. This summer, he will expose more Indigenous youth to traditional ceremonies.

It’s an outcome few would have predicted, given that 55 years ago, Etherington was taken from his family at the age of six for cultural re-programming. His identity was systematically dismantled at St. Anne’s in northwestern Ontario — the notorious residential school that punished children with a homemade electric chair.

“There was a film strip about a coloured boy named Bamboo they played over and over. He needed help, he needed to be fed,” he recalls, speaking about the experience over the phone from Timmins, Ont.

“He is poor and the nuns will help him. They instructed into my blood, into my brain — they felt they had the right to do that. That’s indoctrination, that’s colonization. Is that a dignified way to nurture the intellect of a child? We were dehumanized by the experience. There is never an excuse. The reality is damage.”

By the time Etherington and his peers returned home to Moosonee, Ont. in 1969 (after six years at St. Anne’s) they felt like outsiders in their own community. Deprived of parental nurturing and the guidance of their Mushkegowuk elders, the youth were confused and distrustful, he explains.

Despite the horrors of residential school, he reports, much of the Indigenous population continued to attend church. But it never felt right to Etherington.

This is the story of his evolving relationship with the Catholic Church and the Government of Canada — the entities that tried to wipe out Indigenous culture and its gifts of wisdom for us all.

Stripped of self-esteem and sovereignty

Etherington says it was around the time he returned from residential school to Moosonee that liquor stores popped up in remote northern Ontario communities.

Many Indigenous peoples were vulnerable: emotional trauma inflicted at residential schools combined with underemployment and alcohol abuse created a downward spiral of disempowerment. Etherington was temporarily pulled into this cycle, but overcame it as he envisioned his place in a much larger sociopolitical picture.

“When I made a decision to change my life away from alcohol, also drugs, I realized my decision included who I was (culturally) when I made that decision. I would describe something to you: The head thing happened when I put down the alcohol, then the drugs, smoking up. This initiated for me looking ahead, making a choice.”

This is how Etherington speaks. His words are being shared verbatim because the distinct syntax gives insight into his worldview. I've known him since 2014, when I volunteered my minivan to support one small stretch of his group’s ceremonial walk from Cochrane, Ont. to Ottawa. In the hours spent discussing his story on the phone, I asked him repeatedly to rephrase his thoughts; the importance of his message keeps me present and curious.

My failure to "get it" exactly represents the crux of the challenge of decolonization. Sharing Etherington's way of expressing his ideas gives insight into his character and his culture, hopefully piquing your curiosity too.

Etherington had been brought up with Indigenous values, in a sense. He explains, “My mother’s father was a chief. He took care of his family from the land. But he was also a Catholic.” Etherington’s father knew the traditional means for families to thrive in the harsh conditions of the James Bay Coast and he exemplified the roles and responsibilities of a Cree man. He shared with Etherington “what the wind, the sun, the land and the water were describing to him.”

After St. Anne’s, Etherington continued to attend church in Moosonee, even though it didn’t feel right. He had been inwardly rejecting religion and the colonialist disruption since childhood. A belief system that predates nationalism and religion, and which is more sustainable and aligned with human rights, cannot be stamped out so long as Indigenous people like Etherington are sharing their understanding of the world.

Even now, Etherington doesn’t speak of his leadership role, or the work he does personally; he talks about experiencing harsh realities in Treaty 9 (James Bay) communities, collectively, and bringing about justice for the next generation, also collectively. Individualism is not an Indigenous value.

Unlearning the constructs of church and state

By the time Etherington officially left the church, he was 30 years old with a wife and four children. It was 1986 and Etherington was working seasonal jobs and labour jobs, and doing upgrades that were then called ‘manpower training.’ Though his life and work were modest at that time, he was preparing himself to improve conditions for his community. However, he still wasn’t empowered enough to act on the ideas swirling in his head.

“What am I doing? Who am I? I’m clean and I’m with my family. I come from this established scenario, meaning the community. I knew about hunting and the land as I had been associated through my father. Something in my existence prepared me for something. If you look at my father, without him speaking he prepared me for something.

“Certain impacts can sidetrack people away from it but it always stuck. The standard was set by my father through his respect for the land. Something made me pay attention. It’s okay for me to go to a pow-wow and listen to elders.”

Etherington stepped into his cultural identity as a conscious choice, knowing there would be huge consequences for his relationships with his parents and his children. Sometimes, being authentic means stepping away from the security of convention.

The cost of freedom, to which Etherington repeatedly refers, is the gravity of witnessing one’s own socio-political participation vis-a-vis one’s ethics. Once he recognized the machinations of oppression he could no longer be silent or complicit. Realizing how colonization was ongoing and seeing the social crisis in his home community understandably 'radicalized' Etherington.

“When I went through that process I was physically sick,” he tells me. “I was moving away from something. The next thing I did was to go see my father. I was following traditional ways in front of my parents and they were Catholic.

“I told my parents of my choice to leave the Catholic indoctrination and that, with my family I would step within my native identity. This decision-making — my values, my standards — affected my family. I had children with me and I knew that they were going to be the next generation, the fulfilling of the prophecy of being Indigenous, knowing the land and having the sky world fulfilled.

“My father was listening and he said, ‘I hear you.’ My mother didn’t say too much. My father asked if I went to see the bishop yet.”

Etherington went to see the bishop in 1986 at the Roman Catholic Diocese of Moosonee. As a 30-year-old man — now a father — he walked straight into the local headquarters of the organization that had stolen him from his own parents.

“The bishop had a sense of why I was there. When he asked me who my parents were, I knew he wanted to control things. ‘I know your parents, they’re good Catholics,’ he responded, in a way that showed he wanted more respect and acknowledgement for the church. He was fooling around with me and making me feel like I should kneel to him and I wasn’t there for that. He made an effort, again, to make me feel small and wasn’t present to what I was saying.”

After his meeting in the bishop’s office, Etherington says his parents — well respected members of the church in Moosanee — realized he was serious about reclaiming his Indigenous identity. He realized his ‘radical’ decision could alienate his parents from their own community, so he decided to travel south to Timmins, Ont.

Indigenous ethics and integrity

Etherington’s choice to leave the church represented a tremendous intellectual leap and an act of conscious resistance to cultural assimilation. “My wife and children travelled on the path with me regarding my identity,” he describes. “They learned about Indigenous values and integrity. These standards were the beginning for them.

“This is what I need to share: in my eyes, today, I see the cost of freedom because our culture does not fit within the choices that society offers us. We are manipulated. Even the law negatively affects us.

“Society sets (culturally inappropriate) standards for us. This is what has happened in our own world: our learners, carriers of knowledge and representatives of our next generation are considered below the standards of society.”

This wouldn’t be the case if Canada weren’t dragging its feet in enshrining the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) into law. The declaration was created to guarantee Indigenous populations individual and collective rights, freedom from discrimination and self-determination under international law.

Together, Etherington and his family attended traditional gatherings in Moose Factory, Moosonee and Timmins. He says he didn’t have to go far to find his culture.

“I knew people who were doing sweat lodges and began to learn what they were about. Then, I began to learn from the elders who spoke about the land and the meaning of the symbols, the education from the land, from the wind, the sun, the water and the land.

“I began to listen and understand, then assist as a helper in ceremonies. Somewhere I realized my father had showed me these things, without saying it directly. The Indigenous side of ourselves and our ethical values were there.”

In 1876, the Indian Act had outlawed the observance of Indigenous traditions. Etherington learned that some ceremonial bundles had moved west with knowledge-keepers. Bundles are not just the physical items used in ceremony, but refer also to teachings.

Etherington’s young family connected with the descendants of those who took those bundles from Wikwemikong First Nation, in Ontario, to the Sunchild First Nation in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. Bundles signify a commitment to ceremonies, in the face of colonial disruption, Etherington explains.

“The ceremony keepers were in the mountains because it was not safe in Ontario. We kept learning about it. We learned to be helpers. It became a part of the kids’ lives. There was a teachable process with regards to how (the elders) had been living with that bundle.”

Etherington came to understand the power of ceremony for rebuilding strong people and communities, and saw that the need for it was greater than ever. If Indigenous people have internalized racism, sexism and classism, he says reclaiming their culture can provide a fresh perspective on life and connect them with the inherent value of being Indigenous.

“I pledged myself to be with the land and what that involves. I connected to who we were before the disruption. My kids have the full ingredients but they internalize that there’s something wrong with us. I do not accept that.”

On racism and bureaucracy

Despite his best efforts, Etherington couldn’t shelter his children from the racism they encountered as they grew up.

He says the stereotypes they heard about their culture, the government policies that marginalized them and the media’s omission of Indigenous perspectives were, in the end, stronger influences than his own.

“Today, my children are struggling. They are on the streets. They are under the umbrella influence of alcohol. Our female grandchildren are affected by rape.”

Etherington’s partner is another residential school survivor and elder, Frances Rose Whiskeychan. She was also born in Moosonee, Ont. and today she calls herself a traditional counsellor, a focusing practitioner therapist and a native drug and alcohol counsellor. The two have emerged as strong leaders, supporting those most in need, in their home communities.

“It’s 2018 and we live in Timmins,” Etherington says. “We work in Attawapiskat and throughout the Treaty 9 territory. The work we do for Nishnawbe Aski Nation is with regards to crisis. We see ourselves as professionals working with people who struggle with drugs, alcohol, violence and crime. Certain aspects we deal with in culturally appropriate ways.

“This is said in the bureaucracy: culture can support the process. We say the mandate is showing up and the constitution is represented by the pipe. Governance is elevated by the teaching of the lodges. Sovereignty is represented by ceremonies like the Sundance and its meaning for the people and the land.”

Etherington’s titles are traditional counsellor, focusing practitioner therapist and resolution health support worker. His cultural understanding, gained over three decades of attending traditional gatherings, informs his professional work today.

“We bring that component, through our learning about Indigenous ways, being involved in our communities and being a family.” He says family is so precious to him because he was robbed of that intimacy and that source of strength as a child.

Etherington’s crisis intervention work is funded through Health Canada. He is part of the Mental Health Crisis Team contracted by the Nishnawbe Aski Nation, which represents 49 First Nations within northern Ontario, and the Mushkegowuk Tribal Council.

“Sometimes our work is respected and sometimes it’s not, and that’s the cost of freedom. When you’re involved in the professional process, you become the helper. Sometimes, the treaty office or the tribal council or the band says how we will be involved. Certain entities understand where you’re coming from, but sometimes the office above them doesn’t get it and our participation becomes limited.”

While Etherington’s critically important work is funded, he laments that the process remains top-down in its approach. There are times he’s only called upon, he says, so it can be said there was Indigenous input.

“The Indian Act will say they’re providing services to their standards, but are they culturally appropriate services? The cost of freedom means we uphold the laws of the pipe, we uphold sovereignty. They play with politics against us because of funding and dealing with that is also part of the cost of freedom.”

As bureaucratic processes thicken, it’s harder for grassroots workers like Etherington and his wife to be involved. They’re the ideal people to serve as crisis workers, he explains, because their life experiences help them relate to those in need, and as elders, they bring spiritually-informed compassion to the work.

But the system, he adds, is designed by — and for — non-Indigenous, university-educated social workers. Once again, Etherington runs into the effects of Canada not implementing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

“We run into it. We’ve become less. There is less of our representation now. Look at how services are being provided. What is their mindset to make those decisions?” he asks.

“We run into their walls and they jump to bureaucracy process and things get cut and policies are tighter, the system harder to navigate. It cuts away who we are and the foundation from which we work. We cannot work beyond the boundaries of the funder’s process.”

“Sometimes, these homes we visit are dilapidated and we’re running into professional process that we have to follow and go above people’s heads. Our job is to help the people but it’s easy to become sidetracked or blocked trying to do our work.”

He sometimes feels the most authentic people are the least likely to get funding.

The true cost of freedom

Etherington speaks often about the true cost of freedom. As it stands, the cost of staying on their traditional territories means that Indigenous people suffer from poverty, isolation and inadequate services. Worse is the indifference that leads politicians to deny Indigenous sovereignty and underfund their communities.

“We’re going to practice (our code of ethics) and teach it to our grandchildren so they understand it fully. Mother Earth needs to be recognized. There is a fulfillment that my father taught me. What I have done is to connect with the land and the sky world. The protocols exist. There must be education and an end to the disruption of our ethics and values.”

In the north, he explains, not tackling poverty is killing people. Etherington speaks of “the diseases Indians get like hypertension, depression, PTSD, diabetes, gastrointestinal problems and cancer.” Etherington struggles with many of these medical issues himself and feels doctors blame him for his own poor health. They prescribe all kinds of pharmaceuticals but, “How much of our herbal medicine comes into the picture?” he asks.

Etherington says some Indigenous people in remote areas decline medical treatment because it means travelling hundreds of kilometres, being separated from their families and facing judgement or indifference from medical professionals. So many interconnected issues tear Indigenous communities apart, he says, including inadequate employment opportunities and services, which encourage youth to move away from their culture and their source of strength.

For Etherington, ensuring Indigenous youth have a strong sense of their ancestral values is part of the solution. “There are families out there that have journeyed across this land and have connected to these values and have elevated them in front of their children. Now, we’re ceremonial helpers and my grandchildren will be too. Our culture has always been here and it’s still here and our children have that much.”

Following up on the TRC

A few of the 94 calls to action in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) have begun to make their way into policy, including some affecting service delivery in remote communities. Etherington says, “They are going in the right direction but Canadians must look at that, compared to what’s needed and what’s meaningful.”

He adds, “How the treaties happened, we still need to discuss.” The treaty specific to Etherington’s homeland is explored in Trick or Treaty, a National Film Board documentary in which Etherington’s son talks about what it’s like living with Treaty 9 today.

The TRC was painful and frustrating for residential school survivors. Seeing the process as inadequate, and the Canadian public’s response as negligible, Etherington led a ceremonial counterpart to the official proceedings. He gathered a group to walk from Cochrane, Ont. to Ottawa via Toronto in January 2014, to support healing, show solidarity and raise awareness about the ongoing trauma of residential schools.

“As part of the TRC, it was explained to us that we have to present our truth and our description. From our side, we have to speak and not just have reconciliation dictated,” he says.

“We did a fasting ceremony in the mountains after the TRC walk. There were ceremonies with the eagle staff. After 107 years, this ceremony returned to Jasper, Alberta. Indigenous learning is one TRC recommendation. We went to a course in Edmonton. There are lots of people following the traditional ways of being — learning the language of kindness and sharing.”

Talking back to Ottawa

In April 2018, Etherington and his partner spent five days at Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, as consultants at the office that dictates the conditions of their life and work. Some staff commented that Etherington had taught them more in a week than they’d learned in their entire 25 years of public service. Other staff treated their teachings as if they could be sterilized and neatly tacked onto the agenda, without impacting the overall perspectives and protocols of the department.

“In 2018, we see the recognition of our existence and our ethics needs to be fulfilled. I felt like I wanted to back it up more, how this process is from our side. Our involvement with the treaties is ours to share. How this started is with the cost of freedom: we’re rebuilding our governance and our sovereignty.”

“We need to do this, expand the process and not stay stuck in this place. We’re going to take our place from 2018 forward, [so things will be better for] our grandchildren. Some things are starting to move but [the government is] overstepping boundaries and overburdening our people, our children. Our grandchildren must have rights to the land.”

Apologies for residential schools mean nothing if perspectives like Etherington are ignored. For Indigenous peoples, land is the basis of their culture. All government policies relating to the Indigenous population must recognize the primacy of this relationship and what sovereignty means to them.

“Our grandchildren are special, you see. We face the cost of freedom for them.”

Thank you. Natalie for

Thank you. Natalie for writing this thoughtful piece of writing. Thanks also to Mr. Etherington and his partner for their endless efforts. The blockage of the very people who could and would work with their families and others as social workers is far too long in coming and so slow. When will our government truly recognize and make UNDRIP law and part of the fabric of Canada? Thank all of who who brought this story to publication on National Observer.

Thank you for a very sober

Thank you for a very sober and explicit reporting of this long standing, inhuman encroachment which has affected generations of indigenous peoples and continues to be mishandled to this day.

Comments