Medical care is a hot topic in the run-up to the Alberta election. The key question, as the televised leaders’ debate emphasized, is who can be trusted to protect public funding for medical care. UCP Leader Danielle Smith reaffirmed her “public health care guarantee,” while NDP Leader Rachel Notley reminded viewers of Smith’s past statements regarding private payment.

What no one is asking the leaders is: Who can Albertans trust to promote health and well-being? Which party will preserve health care as a sacred trust by investing to make people well, not just treating illness after they fall sick?

Our new study of the parties' platforms shows the UCP plans to increase annual spending on medical care by $3.8 billion as of 2025-26. The NDP will add $4.4 billion. These are by far the biggest investments promised by either party. Unfortunately, this isn’t all good news if you care about helping Albertans get and stay well.

As Albertans struggle with long wait times and not enough access to family doctors, it makes sense to inject new money into the medical system. But both parties overlook the fact that medical care accounts for only one-quarter of our health. Medical care was never supposed to go it alone — it’s meant to be part of a wider system supporting people with the things they need to be healthy and well, like decent earnings, homes, child care, and a sustainable planet.

These social conditions may not be the first things that come to mind when many people think about health, yet reams of evidence confirm they more strongly influence our health than medical care. As long as Albertans can’t access safe homes, good incomes, quality child care and a healthy environment, our medical system will never be enough to prevent people from dying early.

We’re grateful we can call on fire departments to put out the flames when we need them, but preventing fires is much less deadly, damaging and costly. So it is with health care. Waiting to invest until people are ill is like showing up with hoses once the fire is already raging. We need to prevent the first sparks from getting out of hand. This means clinics and hospitals should be the last stop, not the first stop, in our health system. The first stops for good health are found in our neighbourhoods, jobs, childcare centres and schools — something the pandemic made painfully clear.

Alberta used to budget this way. In 1976, the province spent approximately 36 per cent more on social and education programs than on medical care. Now, it’s about 26 per cent less.

These trends suggest it’s no coincidence that while medical costs rise, access and quality aren’t keeping pace. We haven’t prevented enough people from joining the queue waiting for medical care, especially as our population ages and patient needs become more complex. In response, many doctors want to prescribe things like housing, child care and poverty reduction, but can’t. Instead, many of these medical professionals are burning out, even as the number of doctors per capita goes up. Alberta had 125 physicians for every 100,000 people in 1976, including 68 family doctors. Today, Alberta has 252 doctors for every 100,000 residents, including 124 family physicians.

Unfortunately, both the UCP and Alberta NDP fail to embrace the science of health promotion.

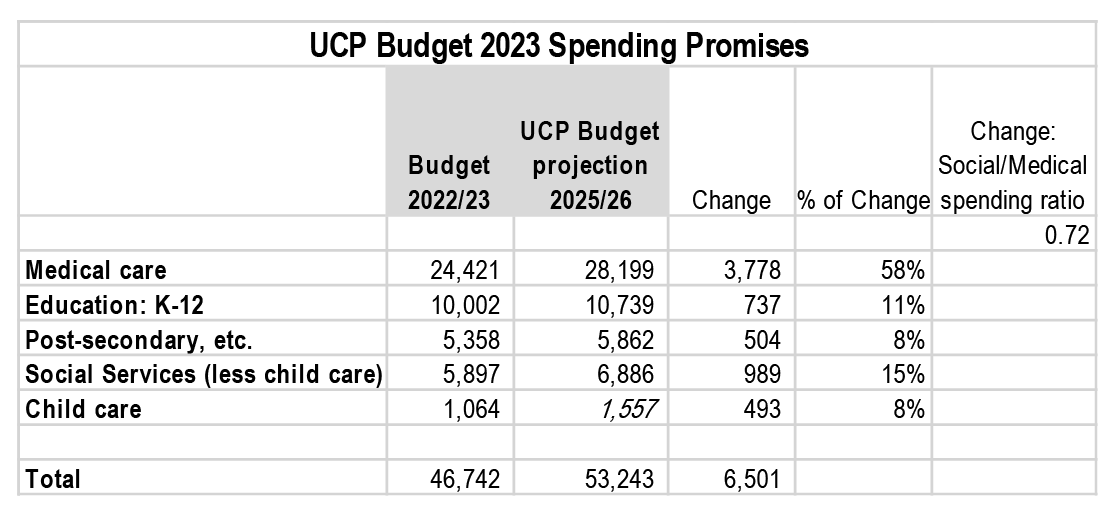

The UCP plans to increase annual provincial spending on medical care, education and social services by $6.5 billion as of 2025-26. More than half (58 per cent) of the new spending will go to medical care, signalling illness treatment is considered more urgent than social spending on prevention and health promotion.

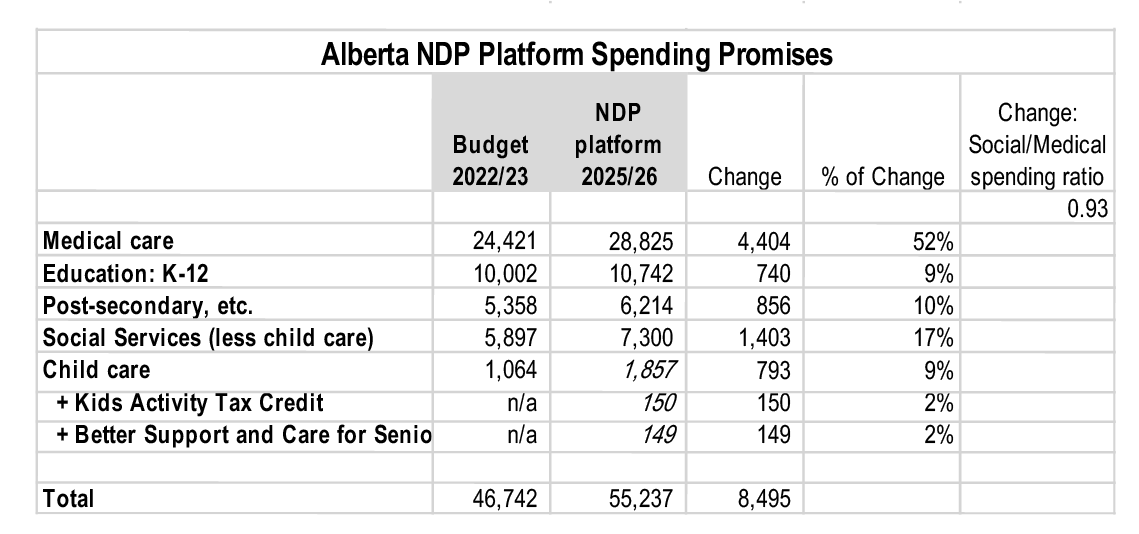

The Alberta NDP intends to spend $8.5 billion more annually on medical, education and social programs as of 2025-26. Of that,52 per cent will go to medical care, confirming the NDP also prioritizes treating illness over prevention. That said, the NDP is closer to aligning with the science of health promotion than the UCP because it offers a somewhat better balance between medical and social spending.

The inherent risk of both parties’ promises is that they will fail to slow the flow of sickness into our hospitals and clinics because they don’t invest urgently enough to promote well-being and prevent illness. An overburdened system is a recipe for burnout for doctors and nurses.

Some Albertans may consider higher provincial spending on medical care as a point of pride. Especially now when so many Canadians are concerned about gaps in our medical system. But the data show this spending isn’t worth bragging about because it does not buy better outcomes.

If more money for medical care was the secret for better health, then Alberta would already be ahead of B.C. and Ontario. Alberta spends $5,427 per resident on medical care, compared to $4,997 and $4,864 in B.C. and Ontario, respectively.

Despite higher spending, the Canadian Institute for Health Information shows Alberta ranks below B.C., Ontario and the national average on health outcomes for infant mortality, heart disease, cervical cancer and rectal cancer mortality, and avoidable admissions for COPD (lung disease) and diabetes. Albertans also have a lower life expectancy.

Even though high spending on medical care doesn’t consistently purchase the best health outcomes for Albertans, it does result in Alberta doctors being the best paid of any in Canada.

No matter what your budget priorities are, it makes little sense for Alberta to spend more per capita on medical care yet not achieve routinely better health outcomes, especially given the province’s younger population. The median age in Alberta is 38, compared to 40 in Ontario and 42 in B.C. A younger population should require lower per-capita spending on medical care because we consume most medical services when frailty increases at older ages.

The size of the opportunity to spend more wisely may surprise readers. Per-capita medical spending in Alberta would remain on par with B.C. and Ontario even if the total budget for medical care in Alberta was $2.5 billion less than it is now. To put that large sum of inefficient spending in context, Alberta only plans to spend $1.9 billion per year for $10-a-day child care.

Since B.C. and Ontario report as good or better health outcomes than Alberta, whatever party is elected to the Alberta legislature on May 29 should grow spending on child care, education, housing and poverty reduction more urgently than spending on medical care. To be clear, we aren’t suggesting medical spending be cut, just that other investments should grow faster.

Social spending invests where health begins — the conditions in which we are born, grow, live, work and age — capturing the wisdom that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

Dr. Paul Kershaw is a University of British Columbia policy professor and founder of Generation Squeeze. Andrea Long is Gen Squeeze’s senior director of research and knowledge mobilization.

They are the authors of a new study of housing commitments made by the UCP and Alberta NDP in the 2023 election. This analysis is part of Generation Squeeze’s non-partisan, evidence-based Alberta Voters Guide. The guide helps to inform Albertans about actions parties are proposing to address key issues in the 2023 election, like affordability, health and protecting natural resources. Follow us at www.gensqueeze.ca, Twitter, Facebook and listen to our Hard Truths podcast.

There wasn't enough use of

There wasn't enough use of the pandemic to assess the overall quality of health care and life, across the provinces. I did my fumble-fingered best to estimate the demographic difference between BC and Alberta:

http://brander.ca/c19#jasonbutcher

...which resulted in me (kidding) stapling Jason Kenney's head on an ad for a "mad butcher" hallowe'en costume, because I roughed-in that BC "should" have had at least 50% more deaths than Alberta, with 1 million more population and older demographics...but it was Alberta that had 15% more than BC. The difference was AN EXTRA 2000 DEATHS in Alberta, compared to BC outcomes.

I don't put that down to a slightly-lower vaccination rate, or significantly-lower masking rate; they just aren't strong enough drivers for that many dead bodies. It's the overall Alberta culture, of which vax and masks were part, distancing was part. Going in to work when you feel bad was part. Socializing "anyway" was part.

And then there's the health care outcomes, as noted here. I see those choices, over the decades, as part of that "overall culture" that places less emphasis on care, more on "powering through" problems, just ignore them, shrug off consequent casualties. It's a mentality that also leads to less environmental care, less consideration for consequences.

You can multiply these comments by two for my thoughts on American culture, which had 3X as many dead/million as Canada, but also 7X as many dead per million if you count only the "pre-retirement pandemic" of deaths under age 50.

http://brander.ca/cccc#dyingyoungsumup

Good work, Roy.

Good work, Roy.

For the record, I'm an oddball. I moved from Alberta to BC when I was 26. It was a nice way to close out the Disco Decade. That was long ago, and now I'm a retired old fart who remains fascinated by the crazy Three Stooges reruns from Alberta, not the least their tendency to kill themselves as Believers (choose your faith / conspiracy theory) and put themselves at risk of economic calamity by partying on like it was last century.

It is also worth noting that

It is also worth noting that not every medical care dollar has equal effectiveness. With the way the UCP are pushing towards privatized service that costs far more, those extra dollars could disappear without a trace. Hopefully, if an NDP government prioritized effective public service, initial increases could be used to get some problems actually solved, leaving less need for increases in the future, so that more money could be used on the social determinants of health.

We should also remember that reducing poverty and so on is not just done with dollars. Increasing the minimum wage, for instance, or regulating the housing market including rent, involve mainly political will, not tax expenditures.

I have seen absolutely zero

I have seen absolutely zero research showing that childcare improves health outcomes of children. In fact, infections requiring medical intervention, last time I saw the numbers, were 6 times as common in daycare youngsters as in home-raised youngsters.

Seniors spend more time with the medical system largely because pollution and bad habits have had longer to affect them.

The one demographic that takes up disproportionate amounts of healthcare spending here in Ontario was demonstrated to be university-educated professionals.

I do wish Mr. Kershaw would stop cherry-picking stats and instances, in order primarily to direct more government spending to the very demographics that consume more government services, including health services and more by way of tax breaks, not to mention more carbon-costly long-distance travel.

Not because it'd help me, or even Mr. K. But his recent self-serving rants have just been bad science.

The truth of the matter is that while the house is burning, first the emergency needs to be dealt with: putting out the fire. That's health-care services. We already devote a fair amount of spending to the likes of universal vaccination programs.

Perhaps Alberta's stats would be better if they weren't so profligate in spreading around environmental toxins, if they hadn't been at the centre of various kinds of Covid denialism, and most importantly perhaps, if they didn't have a disproportionately rural populace compared to other provinces.

The medical care systems in every single province of the country are in "house-burning" category.

And yes, we have more doctors per capita than we had in the 70s, and more family doctors as well: at a time when the baby boomers (whom Kershaw likes to blame as a class of people, for everything bad).

Perhaps when looking at availability of doctors, one should consider the hours they work. At both ends of the spectrum.

Comments