The Stephen Harper government had barely revealed its plans for Canada’s climate targets before environment groups laid into the announcement, criticizing it as meaningless and short-sighted.

Harper likely wasn’t keen to release any details, but with the Paris summit on climate coming up in July 2015, countries are submitting their Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) to the United Nations.

The internationally based World Resources Institute (WRI) is the most recent group to examine the Canadian government’s targets — and find them wanting.

In a blog post in mid-May, the same day as the Harper government’s announcement, the WRI, noted: “Unfortunately, Canada’s level of mitigation would put it — the world’s ninth largest emitter — noticeably behind its peers in terms of how fast it aims to decarbonize in the post-2020 period.”

To be sure, Canada’s aim of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 30 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030 seems underwhelming.

The European Union is targeting 40 per cent below 1990 levels by 2030; and the United States is aiming for 26 to 28 per cent below 2005 levels by 2025.

In the former instance, the EU’s 2020 target is 20 per cent. The EU has actually achieved 19 per cent reductions to date. And the U.S. is reducing essentially the same levels as Canada, but five years earlier.

The WRI notes that developed countries, including Canada, the EU and the U.S., promised more than two decades ago to take the lead in addressing climate change.

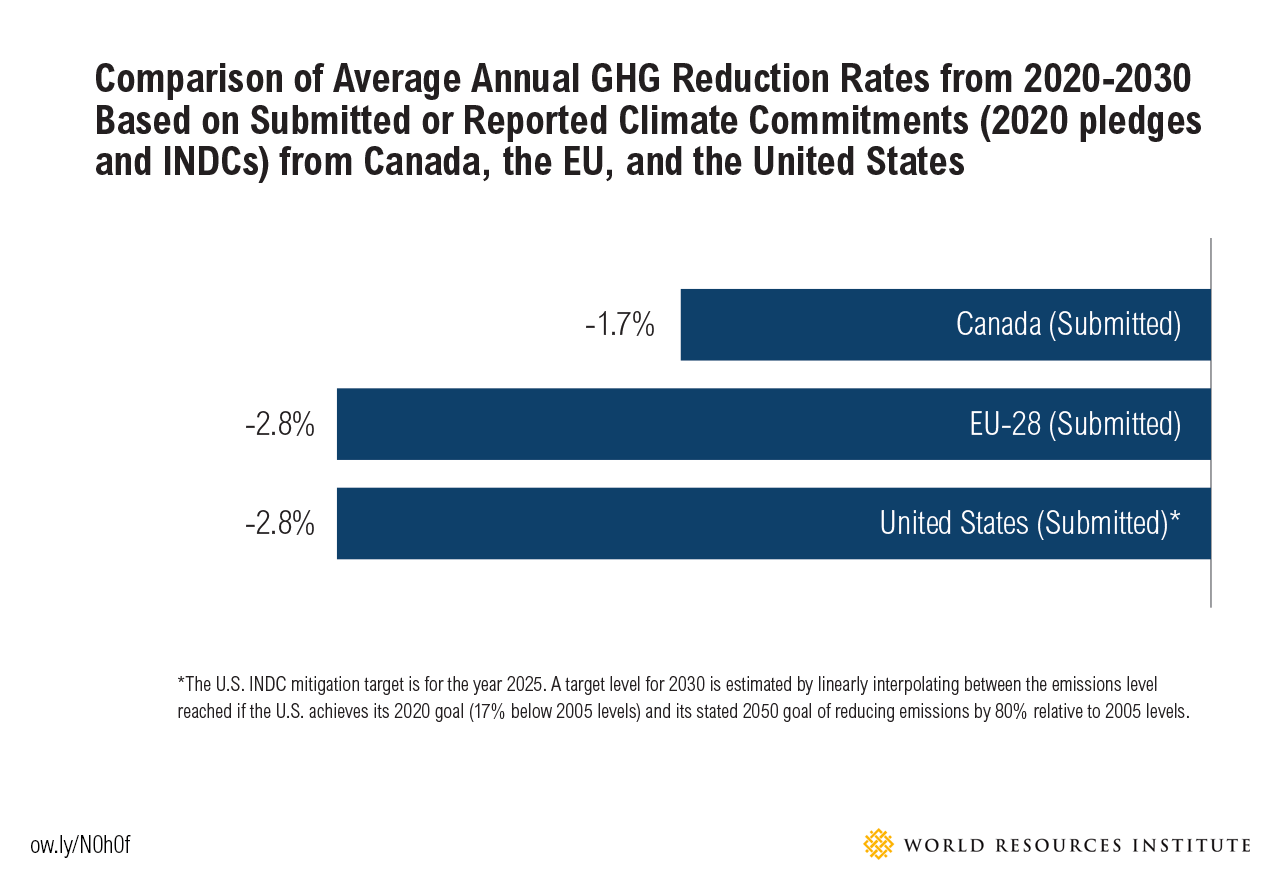

The WRI estimates the EU and U.S. proposals aim to reduce GHG emissions between 2020 and 2030 by approximately 2.8 per cent a year. “Canada’s is significantly less ambitious at 1.7 per cent per year,” the WRI notes.

Previously, Canada had promised to match the U.S. in terms of ambition, the WRI reports.

“Indeed, the decarbonization rate from 2010 to 2020 implied by Canada’s earlier pledge even exceeded those of the EU and the United States over the same time period – though Canada still has significant work to do to get on track to achieve that pledge,” the WRI notes.

“Canada’s 2030 proposal, on the other hand, would put it behind the U.S.”

Amin Asadollahi, the oil sands program director at the Pembina Institute, says Canada is currently on track to miss its 2020 target by about 20 per cent.

“We’ve heard these announcements before,” Asadollahi remarked on the government’s nearly announced targets. “This is like a cycle. You set these ambitious targets down the road, but we have no plans to get there, and this sounds to me like another example.”

Asadollahi said what was missing from the announcement was meaningful action meant to reduce emissions — that and anything about the oil sands.

“The principle reason why Canada’s emissions are on an upward trajectory, why we will miss our Copenhagen target, why we will be poorly positioned at the Paris negotiations is Canada’s refusal to address its fastest growing source of emissions, and that’s oil sands.”

Comments