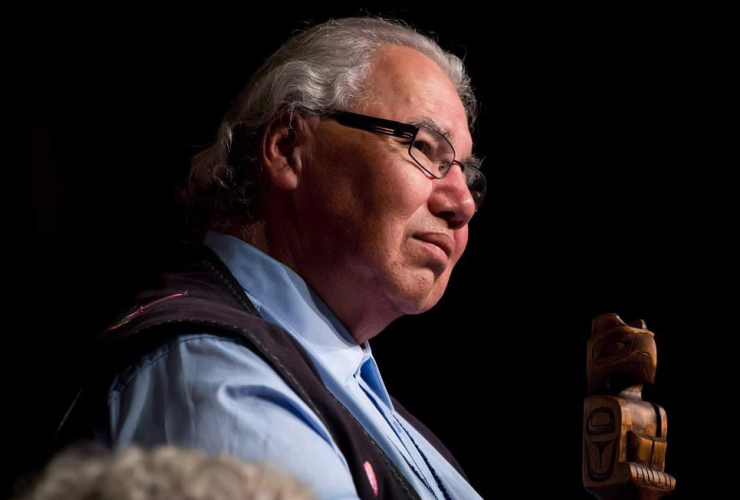

Victims of Canada’s infamous residential schools program are still missing many documents that may be in “churches across the ocean” while other evidence is at risk of being destroyed, Sen. Murray Sinclair said on Wednesday.

Sinclair, Manitoba’s first Indigenous judge and one of three people who presided over Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission that concluded a six-year investigation into the school system in 2015, said there was still a lot of work to do for the victims of abuse in the schools.

“More and more of the documents that were created around the residential school settlement agreement and around residential schools, continue to be in the possession of churches across the ocean and archives that are not available to Canadian law,” Sinclair said at a ceremony hosted in Gatineau, Quebec, by Information Commissioner Suzanne Legault to honour champions of the right to access information. “They’re not accessible, therefore, to survivors.”

Could it be in Kingdom of Denmark?

A Canadian Catholic archbishop dismissed Sinclair’s comments, ridiculing the notion that some records might be overseas.

In a phone interview with National Observer, Archbishop Gérard Pettipas, from the Catholic archdiocese of Grouard-McLennan in Alberta said that all of the incidents involving residential schools happened on Canadian soil, but he doubted that the Vatican or any churches overseas had any records that the Canadian Catholic churches didn't have.

“I don’t know where these (documents) would be,” said the archbishop, who was chairing a group of Catholic entities that reached a multi-million dollar settlement with victims of residential schools in 2006. “In the archives of the Kingdom of Denmark?”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission shared this year’s Grace-Pépin award, given annually to advocates of freedom of information, with Ottawa researcher Ken Rubin. For his part, Rubin has uncovered hundreds of secret government documents, sharing them with countless journalists to report information on a wide range of issues including Canada's record on asbestos, environmental protection, and the conditions in Indigenous communities.

Sinclair, and the other commissioners investigating the residential schools - Dr. Marie Wilson, and Chief Wilton Littlechild - documented horrific cases of abuse suffered by tens of thousands of children in the schools. The institutions were normally run by Christian churches from the 1940s until the 1990s. The system was designed to remove Indigenous children from their homes and strip them of their culture and traditions.

Sinclair, who was recently appointed to the Canadian Senate, said that the right of people to view government records is important since the truth depends on having access to information.

He said the commission was able to get millions of documents out of the archives of churches with their cooperation, but was still missing some documents.

“When they didn't want to cooperate, we had to go to court a few times,” Sinclair said. “The fact that you have to take people to court to make them do what they should be doing voluntarily is a sad comment.”

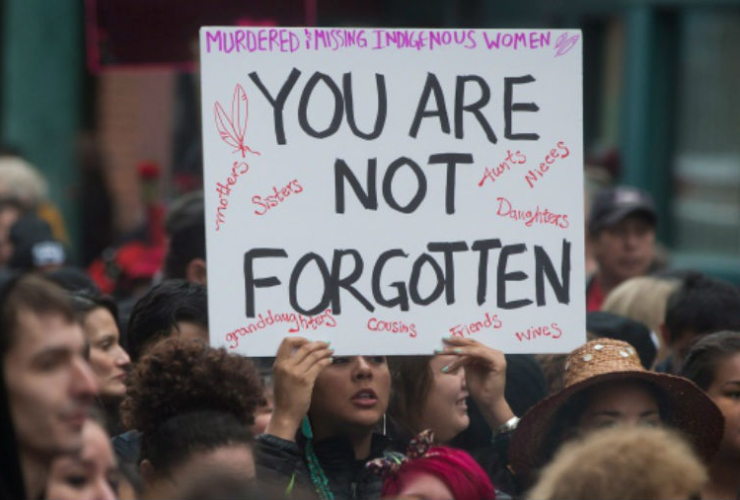

The award ceremony, also coinciding with Indigenous Awareness week in Canada, came a month after the Ontario Court of Appeal decided that victims of the residential schools had the right to decide whether their testimony about their experiences can be destroyed.

That testimony was gathered separately in private hearings as part of a government adjudication process to settle lawsuits. It gave victims a guarantee that their testimony was confidential.

Catholic entities were siding with former students, Archbishop Pettipas said

Sinclair said that some of the victims are being encouraged to push for destruction of the records - an action that he said was supported by church officials.

“Those thousands and thousands of records - over 30,000 individual records and transcripts and testimony are not in our (Truth and Reconciliation Commission) archives. They’re not available to us and the government of Canada is in support of our position that they should be,” Sinclair said.

“But those at the independent adjudication process, and those advising them, particularly the church officials who are supervising their work have long advocated for the destruction of those records. And if those testimonies are destroyed, then the greatest trove of information about what went on in the schools, will be denied to Canadians and to children and grandchildren - the survivors of residential schools. We have a lot of work left, yet to do.”

Archbishop Pettipas said the churches advocated for destruction of records since it was siding with the position of former students who didn't want their names revealed. He said these former students had agreed to testify under these circumstances.

He said he hadn't tried to convince any of the victims to request that these records be destroyed.

“I’ve never talked to any of our former students and tried to coerce them to do that,” he said. “Maybe somebody did but I didn’t.”

Some Catholic entities and officials have apologized for abuse in the residential schools, but the entire church has never collectively apologized over what happened.

Comments