Environment Minister Catherine McKenna said Thursday it was “well within the federal government's right to take action to protect the environment" despite legal threats from Saskatchewan.

McKenna rolled out the Liberal government’s proposal May 18 to implement a federal system that would tax fossil fuels and put a price on industrial-scale pollution.

"We know that carbon pollution causes droughts, fires and floods across our country, and across the world, and that it impacts our health," said McKenna in a speech on Parliament Hill after the proposal was unveiled.

"Making polluters pay is a critical part of any climate plan."

By 2018, each province and territory must have a system in place that prices carbon and meets minimum federal standards, or the government will implement one themselves on that region using a "backstop" system.

Prices are expected to be set at $10 per tonne annually in 2018 and increase by $10 each year to $50 per tonne by 2022.

British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario and Quebec already have carbon pricing systems in place, and officials say most other provinces are moving towards some sort of plan.

Saskatchewan, however, is threatening to take the federal government to court for imposing the price on an unwilling province. Premier Brad Wall referred to the proposal as like "a ransom note" on Thursday.

The details are contained in a “technical paper" on which the government is now seeking public feedback. The paper and public commentary will form the basis of legislation expected to be introduced this fall, said officials at Environment and Climate Change Canada.

“It’s a really good starting place, and there’s tons and tons of work to be done from here, but this is a really positive step forward,” said Catherine Abreu, executive director of Climate Action Network Canada.

“We all know carbon pricing isn’t the be all end all of climate action, but it is an important piece of the puzzle, and it’s really exciting to see us moving on this.”

How carbon pricing will work

As was established in Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s climate plan in December last year, provinces will be given the flexibility to implement different types of systems.

A key element proposed by the position paper, however, is that if provinces don’t fully meet a federal benchmark, the government will “top-up” or provide supplementary elements to those provincial systems. For example, if a province has a gas tax, but it’s not stringent enough, the federal government will add its own portion to compensate, said officials.

The government calls its approach a “backstop" that will ensure that provinces both implement a system, and that those systems are held to a federal standard over time.

The plan is composed of two key parts: a fossil fuels tax, and then a price put on pollution that industrial emitters will either have to pay the federal government for, or trade in "credits" that they've accumulated.

McKenna said “every penny” collected on carbon pricing “will be returned into the province where it was collected," but the government still needs to figure out how exactly that will work.

The tax on fossil fuels is likely to come first, after it’s established in law a year from now, at the earliest.

The fuels tax won’t apply to the four provinces of B.C., Alberta, Ontario and Quebec or any other province that already has a carbon pricing system in place when the system kicks into gear. It will only apply to fuel that is “produced, imported or brought into” a jurisdiction where the federal government is providing this “backstop” or underlying system.

The fuels tax will be slapped on oil and gas companies that produce or distribute fossil fuels. It will apply to all liquid, gaseous and solid fuels, such as gasoline and diesel, natural gas and coal.

Pricing will vary depending on a rate schedule for different global warming potentials that are based on the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s standards. For example, gasoline will be taxed at 2.33 cents per litre in 2018 pricing, while jet fuel will be taxed at 2.58 cents per litre. In 2022, those taxes rise to 11.63 and 12.91 respectively.

The position paper has three charts setting out the price for each solid, liquid and gaseous fuel for each year from 2018 to 2022.

The second part, a price on industrial pollution, will be intensity-based and apply to all industrial facilities that emit 50 kilotonnes or more of carbon dioxide equivalent per year. This so-called “output-based” system will apply a carbon price to the pollution of an industrial emitter that is higher than the federal standard. Polluters that go over the limits can either pay a carbon price, or use up “credits.”

Companies that come in under the standard will be issued credits.

Smaller industrial facilities that don’t go over the 50-kilotonne threshold can still opt into the system. The output-based system will likely come into play a year after the fuels tax, said officials.

That’s because in order to bring them into play, Canada will have to implement regulations. The government will need to figure out which jurisdictions will require which regulations, based on the different systems in each province.

How it will play out in each province

That federal model is similar to Alberta’s, which taxes many types of fossil fuels and uses cap−and−trade for large amounts of industrial pollution. Ontario and Quebec, meanwhile, use cap-and-trade systems, and B.C. also has a carbon tax.

McKenna said Thursday she was “very confident that provinces across this country are committed to working with the federal government.”

She stressed repeatedly in her appearance before reporters that "more than four out of five Canadians live in a province where there is already a price on carbon pollution" and that "almost all provinces" have committed to one by 2018.

All the other provinces that signed the Liberals’ Pan-Canadian Framework on Climate Change are actively looking at implementing a carbon pricing system, officials said.

That leaves Saskatchewan and Manitoba, the latter of which promised in its Nov. 21, 2016 speech from the throne to introduce carbon pricing.

The federal government believes it has a strong case if Saskatchewan goes to court. Departmental officials said there was a strong and well-established constitutional basis for taking federal action to protect the environment and human health.

If the province tries to argue for provincial jurisdiction over revenue, they said, the government could argue that carbon pricing isn't a tax; it's for the purpose of changing behaviour.

McKenna said she’s had “more than maybe a dozen meetings” with Saskatchewan Environment Minister Scott Moe about carbon pricing. In comments to reporters, she appealed to the “progressive” elements of the province.

“Saskatchewan has always been a very progressive province. It’s the province that brought in universal health care. I know people in Saskatchewan care greatly about our environment,” she said.

Chris Ragan, chair of Canada's Ecofiscal Commission, a non-profit environmental economics organization, said he would be “very surprised” if the federal government loses a constitutional challenge over the upcoming law, if passed.

“The environment is a shared jurisdiction between the provinces and the federal government,” he said. “So it seems to me that it’s pretty clear that both governments have both the right and the responsibility to act in this space.”

How it could help Canada reach its 2030 targets

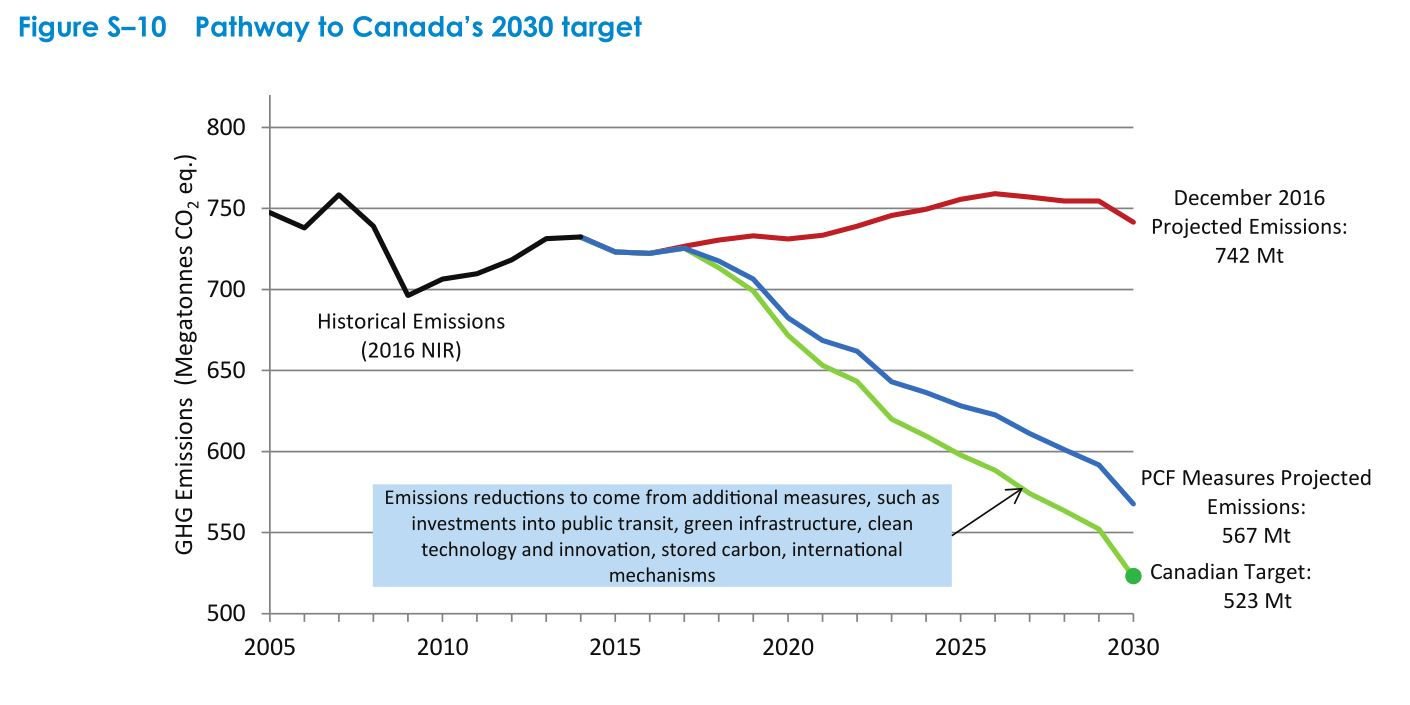

Canada committed in 2015 to cut climate pollution 30 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030. Government officials have admitted Canada will miss that target by a wide margin unless more drastic action is taken.

The question hanging in the air in Ottawa was whether the system as proposed would be enough to get Canada to its target. The country will need to slash emissions by roughly 200 million tonnes over the next 13 years.

Ragan said how well Canada does in getting to its target depended not just on getting a carbon price in every jurisdiction, but where the carbon price goes after 2022.

“It’s not specified where it goes beyond that,” he said. “I think I can say pretty surely that in order to come anywhere near our 2030 targets nationally, we need a carbon price across the country that’s going to be rising pretty significantly between now and 2030."

The proposal doesn't lay out how fast or at what pace those prices are going to rise after that date, he noted.

The government is now accepting public comments on the proposed federal path forward for carbon pricing until June 30, 2017 that it said would help it design the system and craft the law expected to be put in place.

The public can comment on the plan at [email protected].

Comments