This is the second chapter in a four-part series investigating apparent institutional biases within the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the RCMP. The first chaper can be read here.

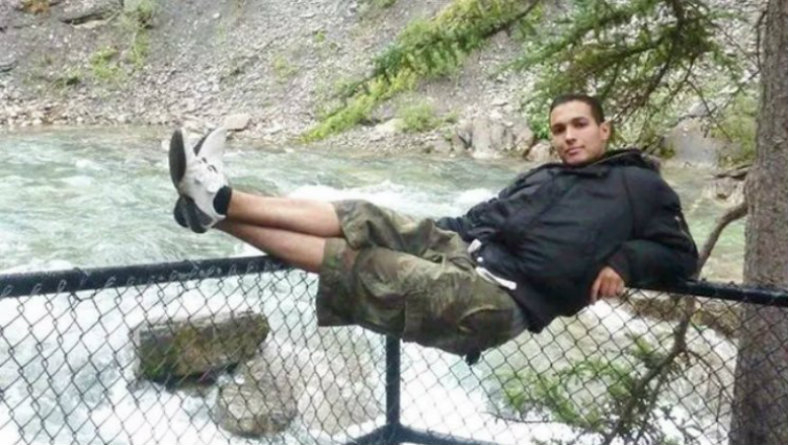

On May 24, 2016, Abderrahmane Ghanem and his parents flew to Algiers, the capital of Algeria, from the Arabian Peninsula country of Oman. After landing and clearing customs, they were met at the airport’s exit by three men in civilian clothes who asked to speak to Ghanem. Privately and briefly. The former Calgary resident, a handsome 29-year-old Canadian with close-cropped dark hair, was led away. He did not return.

Ghanem was now in the hands of the DSS, Algeria’s state security agency – notorious for its use of torture and secret detention. He was about to spend more than a year in an Algerian prison, where he says he was tortured.

Why and how did Ghanem end up incarcerated in Algeria?

Ghanem’s Vancouver-based lawyer, Gary Caroline, believes his client was a victim of a form of “extraordinary rendition” employed by Canada’s spy agency, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS). “All known facts indicate that Canada has actively outsourced the detention, interrogation and prosecution of a Canadian citizen for theorized or suspected activities which apparently took place in Calgary more than four years ago,” Caroline wrote in a letter to Chrystia Freeland, Canada’s minister of foreign affairs, this past June.

In fact, Ghanem is one of at least half a dozen Canadian citizens who’ve been arrested, imprisoned and interrogated by foreign governments at the behest or suggestion of CSIS and the RCMP. Torture was used in all, or nearly every one, of these cases. This practice raises questions about the biases of CSIS and the RCMP, in particular towards Arabs and Muslims. When asked if she thinks her husband, Maher Arar, would have ended up being tortured in a Syrian prison if he'd been a white Christian, Arar's wife, Dr. Monia Mazigh, says: "I would have absolutely strong doubts that it wouldn’t be the case if he would have been someone with a different name, with a different religion with a different cultural background."

Extraordinary rendition — the Canadian edition

The practice of “extraordinary rendition,” as it's been called, flourished after 9/11 when the CIA and other intelligence agencies established secret detention, interrogation and torture programs. All told, 54 countries, including Canada, participated in this operation.

But there was more than one version of this system. One was run by the CIA and involved apprehending suspected terrorists, transporting them on U.S. government airplanes to secret CIA-run prisons (known as black sites), where they could be freely tortured and interrogated. This program ran from 2001 to 2007 before the U.S. government closed it down.

The second version involves the interrogation and torture being outsourced to foreign regimes, mostly in the Middle East or Africa, where the rule of law is weak. The Washington Post reported that a U.S. official involved in this method said the understanding was: “We don’t kick the shit out of them. We send them to other countries so they can kick the shit out of them.”

Typically, this kind of detention and interrogation program involves suspects being arrested while they're travelling, and tortured and interrogated by local secret police – at the request or suggestion of Western intelligence agencies. Moreover, questions for the detainees are supplied by Western intelligence agencies. “It’s a global phenomenon, it’s not just Canada, and we understand it is continuing apace,” says Julia Hall, an Amnesty International lawyer based in London, U.K., who says the U.S. and European governments are still utilizing this form of detention and interrogation.

This technique was embraced by CSIS and the RCMP – who appear to be still using it, as reflected in the Ghanem matter. Alex Neve, secretary general of Amnesty International Canada, calls it “extraordinary rendition, the Canadian edition. We didn’t have our own fleet of secret spy planes to ferret people off to Syria and Egypt etc., but through a well-placed phone call and a reckless or intentional sharing of intelligence, (CSIS and the RCMP) could accomplish the very same goal.”

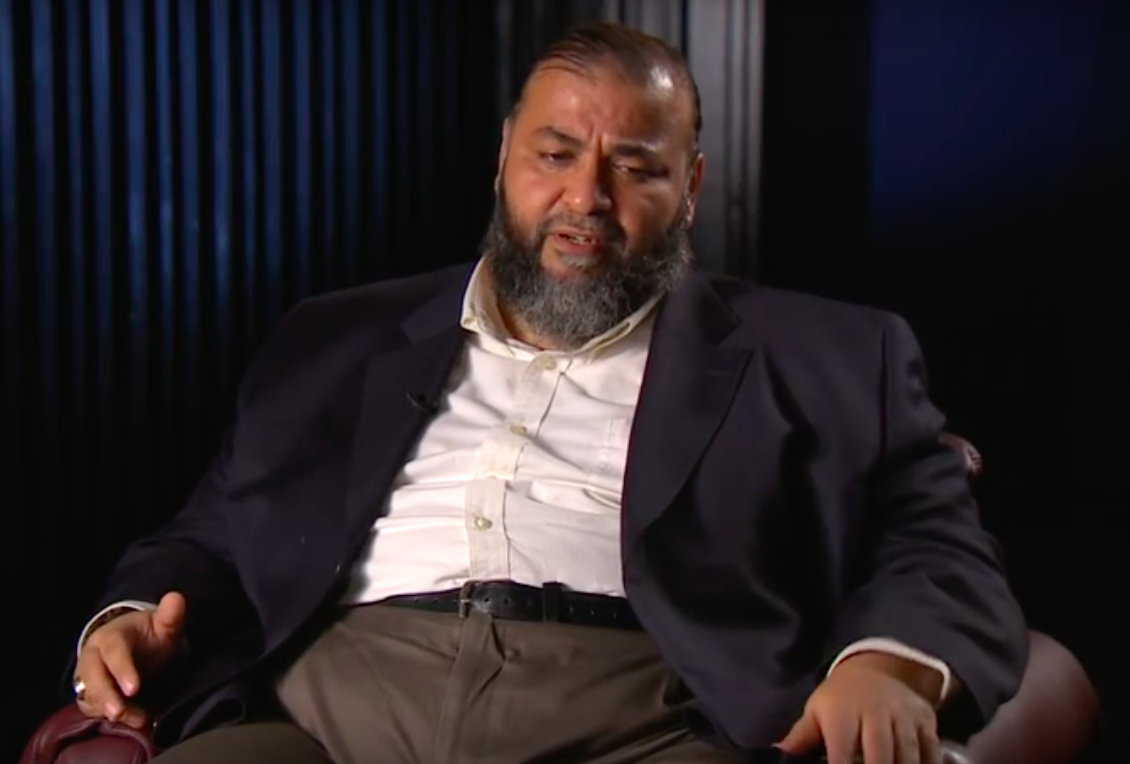

Phil Gurski, who spent 12 years as a CSIS analyst (he left the agency in 2013) disagrees with the word “rendition” being applied to what Canada is doing. “What rendition suggests is that CSIS had an active role in directing somebody or sending somebody to a different country – and that is categorically false,” he remarks. “What CSIS does, and what CSIS is authorized to do under section 17 of its act, is to share information with a foreign partner... So there is a process that the service goes to say, ‘Okay, here’s what we know’ – we know these guys have independently travelled to these countries, they weren’t rendered, they weren’t forced, they weren’t urged or hoodwinked, they went there and we need to find out what’s going on because they are of interest to us for legitimate reasons. Are we okay to actually exchange information with those states? And that’s kind of how the process works.”

Yet Phil Tunley, a Toronto lawyer who has represented subjects of this detention method, observes: “All of these activities are prohibited by Canadian law. When they do these things, they are breaking expressed requirements of Canadian law and ministerial directions and policies that are supposed to be binding on the RCMP.”

More troubling, in the case of Canadian citizens who’ve been detained in this fashion, any evidence that they are terrorists, or pose a real threat to Canada, has never been made public.

Consider the following.

Abdullah Almalki

A Syrian-born businessman who lives in Ottawa with his six children, Almalki spent some time working for a charity in Afghanistan called Human Concern International (HCI) in the early 1990s. HCI also employed Ahmed Said Khadr (the father of Omar Khadr), who's believed to have joined al-Qaeda sometime in the ‘90s. But Almalki clashed with Khadr and left HCI in 1994. “You have to realize most Muslims in Canada have some kind of knowledge, or have met or been introduced to or heard Mr. Khadr,” says Tunley, one of the lawyers who worked on the case. “He would tour all of the mosques and raise money (in Canada) for war orphans... (Alamlki and Khadr) did not get along. Almalki left and never worked with him again.”

But Khadr’s purported ties to al-Qaeda meant, in the eyes of CSIS and the RCMP, Almalki was an al-Qaeda sympathizer as well. After 9/11, Almalki became the focus of a massive investigation by the RCMP, although their own officers found it “difficult to establish anything on him other than the fact that he is an Arab running around," according to one internal memo. The RCMP considered Almalki an “imminent threat” and an “Islamic extremist.” He was put on a watch list if he left Canada. When he departed Canada in the fall of 2001 to travel to Malaysia, the RCMP passed this information on to the FBI, who shared it with the CIA. While Almalki was in Malaysia, CSIS kept tabs on him. In May of 2002, Almalki flew to Syria to visit relatives and was arrested at the airport in Damascus by Syria’s military intelligence.

He spent 22 months in Syria, mostly in the country's most notorious prison, where he was subjected to interrogation and torture by way of beatings, whipping his feet with an electric cable and lashing his body. The RCMP passed on questions to his Syrian interrogators to put to Almalki. He stayed in solitary confinement for 482 days in a cell not much bigger than a coffin, which he says was overrun with rats, cockroaches and lice. Almalki was put on trial in Syria in 2004, which led to his release.

Maher Arar

Arar came to the attention of the RCMP and CSIS solely because he knew Almalki. In September of 2002, Arar, a Syrian-born engineer living in Ottawa, was detained at JFK Airport in New York on his way home to Canada from Zurich, travelling on his Canadian passport. By then, the RCMP was tracking Arar’s movements.

The American authorities held him for nearly two weeks before putting him on a plane to Jordan, and ultimately to Syria. Arar was held for 10 months by Syrian military intelligence in a cell he described as being the size of grave – a dark, wet, rat-infested, one-by-two metre chamber. Arar said that during his initial weeks he was whipped with an electrical cable. The physical attacks were later replaced with psychological torture. CSIS visited with Syrian intelligence while Arar was incarcerated but did not seek his release. The Syrians let him go in 2003.

Ahmad Abou-Elmaati

A truck driver of Syrian and Egyptian origin, and also an acquaintance of Almalki’s, Elmaati was stopped crossing the U.S.-Canada border in August of 2001. A map of some government buildings in Ottawa was found in the vehicle. As it turns out, truck drivers are frequently given this map to make it easier for them to make deliveries: and in this case, Elmaati said the map did not belong to him. But CSIS and RCMP saw a more suspicious purpose – and shared information about Elmaati with the FBI and foreign intelligence services. Hence, when Elmaati flew to Syria in November of 2001 to get married, he was arrested at the Damascus airport. In prison, the Syrians beat him repeatedly, kicking and punching him in the face and striking him with electrical cables. This went on for a few days until Elmaati, unable to tolerate the torture, falsely confessed to planning an attack in Ottawa. He too was held in a vertical coffin-sized cell. In January of 2002 he was sent to Egypt where he was tortured regularly for almost two years while moved from prison to prison. Elmaati was allowed to leave Egypt and return to Canada in early 2004.

Muayyed Nurredin

An Iraqi-born geologist, Nurredin travelled to the Middle East in the fall of 2003, visiting his family in northern Iraq. By then, CSIS had told U.S. and foreign intelligence agencies they thought he was a financial courier for Islamic extremists. The RCMP had him under surveillance before his trip and shared his goal of travelling to Iraq with the CIA and FBI. While crossing the Syrian border on his way to Damascus, Nurredin was detained by border guards. He was taken to a military detention centre where he was tortured, with the soles of his feet whipped with a black rubber cable. He was asked questions about people he knew in Canada. He was freed after 33 days and left Syria.

Abousfian Abdelrazik

A native of Sudan who came to Canada as a refugee in 1989 and lives in Montreal, Abdelrazik is currently suing the Canadian government and former foreign affairs minister Lawrence Cannon for $27 million. From the late '90s until 2003, Abdelrazik says he was under surveillance and visited frequently by CSIS agents. Abdelrazik knew Ahmed Ressam, the so-called Millennium Bomber, who tried to drive across the U.S.-Canada border to detonate a bomb at the Los Angeles airport in 1999. Abdelrazik even testified for the prosecution at Ressam’s trial. Abdelrazik also knew other Islamic militants, and CSIS became convinced he was "one of Canada's most dangerous and violence-prone Sunni extremists."

In early 2003, Abdelrazik flew to Sudan to visit his ailing mother. Just as he was planning to return to Canada, Abdelrazik was picked up by the Sudanese secret police. Abdelrazik’s lawyer, Paul Champ, says evidence shows CSIS asked the Sudanese authorities to arrest Abdelrazik. In fact, two CSIS agents visited him in custody in Sudan to interrogate him, asking him about people he knew in Montreal. The agents even threatened him, according to Abdelrazik's lawsuit. He says the Sudanese secret police tortured him for months. Finally in July of 2004, he was released and told he could fly back to Montreal. But the U.S., with the support of the Canadian government, placed him on a no-fly list and he couldn’t leave Sudan. By then his Canadian passport had expired, with Canadian officials refusing to renew it.

In the summer of 2005, the Sudanese Ministry of Justice exonerated Abdelrazik of being associated with al-Qaeda. That fall, Sudanese intelligence services arrested him again and took him to one of Sudan’s worst prisons. There he was beaten with rubber hoses for months before being released again in 2006. But he still could not return to Canada. Fearful of being executed by the Sudanese, in 2008 he moved into the Canadian embassy in Khartoum, where he spent more than a year. He was finally allowed to fly to Canada in 2009, despite efforts of the Harper government to block his return.

Internal RCMP and CSIS documents expose their role

Internal RCMP and CSIS documents that emerged in these cases – due to lawsuits or official inquiries – reveal the men’s travels were closely monitored by CSIS, the RCMP and the Americans as the men travelled abroad. The intelligence agencies freely shared information with one another. “The co-operative relationship between the RCMP and its foreign partners regarding the ongoing campaign against terrorism is of the utmost importance,” notes a 2002 secret RCMP memo.

In November of 2001, for example, as Elmaati set off to Syria to get married, two RCMP officers were on the plane to keep an eye on him. They would follow him as far as Vienna, “to insure that he boards the flight to Syria,” says one RCMP memo. By then, another RCMP memo admitted “Our investigation to date has supplied little information to show any criminal activity involving EL MAATI.” Elmaati was arrested upon his arrival in Damascus.

In a top secret memo in December of 2001, the RCMP makes mention of the need “to intercept AlMalki (sic) prior to his return to Canada.” In a handwritten note dated November 2001, an RCMP official notes that he advised an FBI agent of Almalki’s travel to Malaysia. This FBI agent, in turn, “advised they he would relay the information (to the CIA).” In a 2006 RCMP summary of their operations, the document notes that in early 2002, the RCMP became “aware US authorities have placed ALMALKI on a watch list that will cause him to be detained if he travels.” (Elmaati was on same watch list.)

CSIS and the RCMP were aware that by passing on information to the Americans, the U.S. officials would inform foreign regimes of the men's travel plans. In a heavily-redacted July, 2003 letter to American authorities, CSIS advises them of the travel plans of Nurredin, saying “should we be able to confirm the dates of his travel, we will inform you on a priority basis.” Nurredin was grabbed by the Syrians that fall after crossing the border into Syria. Later, while in Syrian custody, CSIS forwarded specific questions they wanted the Syrians to ask Nurredin, including, “Did you receive money from anyone during your travels? Who did you give it to?” (Nurredin was suspected of being a courier of money for Islamist groups).

In January of 2003, the RCMP’s Middle Eastern liaison officer in Rome, Dennis Fiorido, sent a confidential letter to General Khalil of Syrian military intelligence, in which he forwarded questions they wanted put to Almalki, who was by then in prison in Syria (and being tortured). In the letter, Fiorido said he would like to meet with the general’s personnel. “Also be aware that we are in possession of highly sensitive documents and information... Our Service is readily willing to share this information with your Service.”

In total there were three pages of 23 detailed questions the RCMP wanted the Syrians to ask Almalki. Yet earlier, RCMP personnel were saying in memos that in discussions with CSIS, “they were unsure as to ALMALKI’s terrorist related activities admitting that at times they felt he was infact (sic) involved and at other occasions felt he was simply a business man potentially operating outside the law.” This same memo also raised questions about the links between Almalki and alleged al-Qaeda sympathizer Ahmed Said Khadr, saying the two men disliked one another.

In the case of Abdelrazik, internal CSIS correspondence reveal a cavalier attitude towards his plight. In a classified email from a Canadian foreign affairs official to a CSIS officer in late 2003, after Abdelrazik was in Sudanese custody, he said, "the Sudanese have told us that the only reason they are holding him is because we (i.e. Canada) want him to be detained." The CSIS official notes that as a Canadian citizen Abdelrazik can return to Canada but added, "Unfortunately, we are equally certain he knows how to use his Canadian 'citizenship of convenience'...to advantage to return to Canada where he will once again pose a serious threat to the security of other Canadian citizens and the interests of our allies."

Four years later, with Abdelrazik still stuck in Sudan, in November of 2007, both the RCMP and CSIS admitted in letters that after examining their files, they had no information suggesting he was involved in any criminal activity or posed a problem.

All told, the correspondence and other documents suggests that CSIS and the RCMP knew the men were being tortured. In a series of email exchanges among RCMP officers in November of 2001, after Elmaati was detained in Syria, one RCMP officer mused to a colleague that if Elmaati was arrested by Syrian police he will be “’interrogated’ (Syrian style).” In a secret RCMP briefing note from the summer of 2002, they noted that indicators were that Elmaati “has been exposed to extreme treatment while in Egyptian custody.” In the same memo, it notes that the RCMP "have also exposed the Islamic extremist community to intense scrutiny resulting in the foreign travel of persons linked to bin Laden, resulting in their apprehension and detention in foreign jails, under less than desirable conditions."

In 2010, Wikileaks released internal US government diplomatic documents, among them minutes to a 2008 meeting between then CSIS director Jim Judd and a US State Department official in Ottawa, where they discussed terrorism threats. In the minutes, it notes that Judd "derided" legal strictures placed on CSIS by Canada's courts. "These (court) judgments posit that Canadian authorities cannot use information that 'may have been' derived from torture, and that any Canadian public officials who conveys such information may be subject to criminal prosecution," the minutes note.

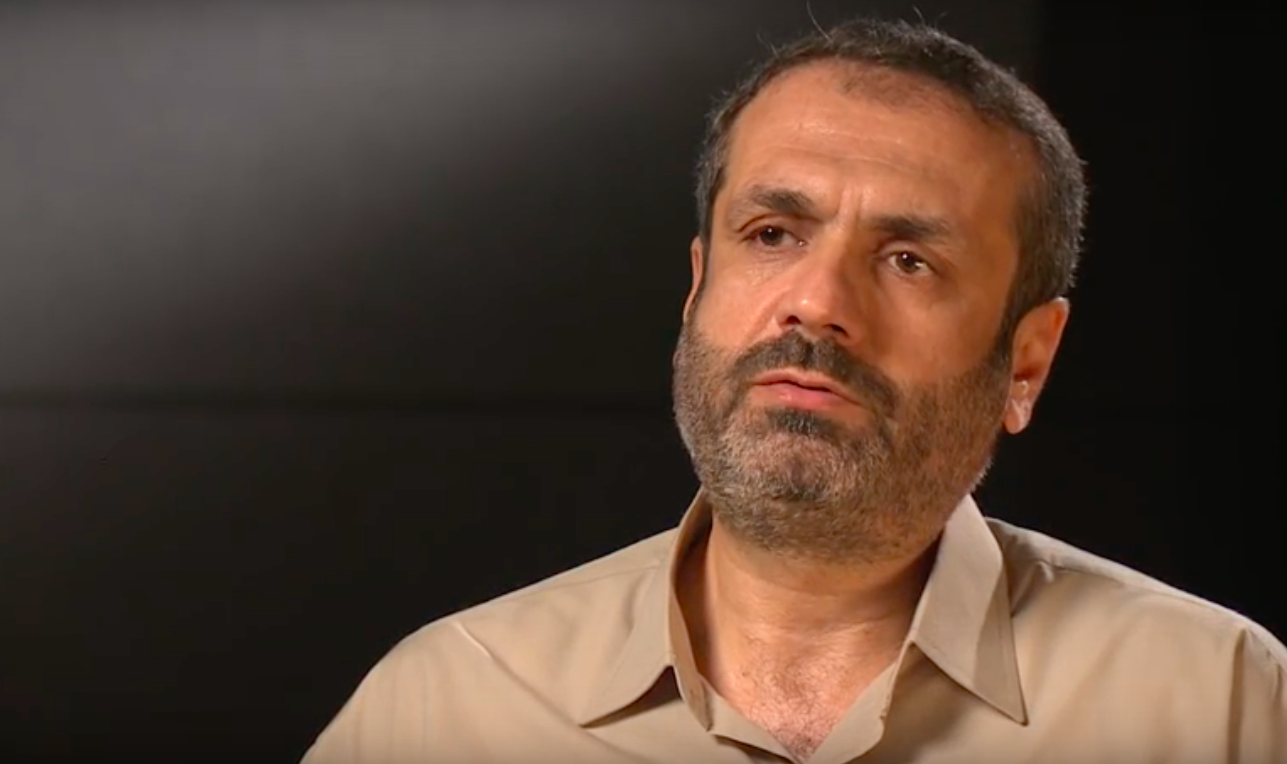

Victims sue feds for hundreds of millions

In the first four of these cases, two government inquiries led by esteemed judges – one in 2006 and the other in 2008 – established there was no evidence the men were linked to terrorism and found that CSIS, the RCMP and Canadian authorities were most likely responsible for their incarcerations abroad. “Almost all of the conduct involved directly Canadian officials,” says Tunley, who represented Elmaati and Nurredin. “(CSIS officers) visited Syria and Egypt, they met with Syrian and Egyptian officials who had these fellows in custody, they sent questions that they asked Syrian and Egyptian officials to put to Elmaati and Almalki in custody.”

Yet former CSIS analyst Phil Gurski is comfortable with CSIS and the RCMP’s actions in these cases. “I think the role that CSIS and RCMP played was entirely consistent with their mandate, entirely consistent with the fact that they been charged with protecting Canada, keeping Canada safe,” he says. “Am I happy with what allegedly happened to those gentlemen? Clearly not. I’m not a believer in abuse, I’m not a believer in the use of torture, I’m not a believer in the use of force to gather information. But I think the service and the RCMP acted consistently within their mandates.”

Tahera Mufti, a CSIS spokesperson, did not respond to this investigation's queries about whether the agency has used a form of extraordinary rendition, and simply said: "It’s important to note that individuals with extremist views who seek to undertake terrorist activity, whether they remain in Canada or travel abroad, are the most pressing threat Canada faces and are, as such, the primary focus of CSIS investigative resources. CSIS is mandated to investigate activities suspected of constituting threats to the security of Canada, and to report on these to the Government of Canada."

Karine Martel, a spokesperson for Public Safety Canada, speaking on behalf of the RCMP, says the government "opposes the use of torture or other unlawful methods of investigation in the strongest possible terms. The Criminal Code and Canada’s international obligations prohibit the use of or participation in torture. All RCMP operations must respect the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canadian law and our international obligations."

"Following concerns raised in the (2006 and 2008) Inquiries," Martel added, "the Government has taken steps to ensure this will not happen in the future including, amongst other things, improving how departments work together on national security files, adding safeguards to how it uses and shares information with other countries, strengthening the training for its national security agencies, and investing more resources into consular services for Canadians abroad... In addition, Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale is revising the Ministerial Directions with regard to the use of information derived from, and sharing of information that contribute to, mistreatment, including torture."

Elmaati, Nurredin and Almalki each sued the federal government for $100 million. Tunley says the men suffer from PTSD and "the reality is that their lives have been shattered. They cannot move forward with any kind of employment because of the stigma... (and) the continued shadow of allegations that were made by Canadian investigators." He says that due to their medical conditions "our clients essentially are unemployable."

However, the government refused to settle these cases for nine years, which was scheduled to go to trial earlier this year. On the eve of trial, the federal government finally paid out an undisclosed sum, along with apologies. Arar had received $10-million and an apology in 2007.

In the case of Abdelrazik, his lawsuit continues, although a 2009 court ruling said the evidence shows CSIS was responsible for his arrest in Sudan. “We found there were all these internal documents saying that CSIS asked (Sudanese authorities) to arrest him,” says his Ottawa-based lawyer, Paul Champ. “In disclosure we’ve found some pretty offensive comments about him, saying he was a second-class citizen.” The government will not comment on this case.

The case of Abderrahmane Ghanem — déjà vu all over again

Yet, despite the payouts and bad press these cases generated, the story of Abderrahmane Ghanem suggests CSIS and the RCMP have not stopped outsourcing their interrogation (and possible) torture to foreign regimes.

Ghanem was born in Algeria before his parents moved the family to Canada in 1997. They settled in Calgary and became citizens in 2001. His father is a geophysicist and works in the oil industry.

Ghanem studied to become an IT administrator and consultant. In his last two years in Calgary, he hung out with a group of young men at a mosque in Calgary who were growing radicalized over how Muslims were being treated overseas. Seven of the young men went on to fight in Iraq and Syria for various Islamist groups, notably ISIS, and most were killed in these countries.

Ghanem did not follow this path. In 2012 he moved to Algeria to look for work. The last time he any contact with anyone from the Calgary mosque was in early 2013, says his lawyer, Gary Caroline. While Ghanem was abroad, he and his family were contacted by RCMP and CSIS regularly, who interviewed Ghanem on more than one occasion.

In February 2015, for example, he applied to renew his Canadian passport. He was contacted by a Canadian official and told to come to the embassy in Algiers, where he was living. There he met a man and woman. The man, called “Philippe” – presumably a CSIS agent – aggressively questioned Ghanem about his Calgary friends, even accusing him of lying at one point. They told Ghanem to return the next day, suggesting that if not, "other sides would not be too nice to you." Ghanem did not go back. Instead he complained to CSIS. Two weeks later, he was stopped while leaving Algeria for Oman, where he was asked: "Why are the Canadians after you?"

By then, Ghanem had already been denied entry after he'd tried to travel to Turkey and the UAE.

In early 2016, Ghanem was living in Oman. There he was arrested by Omani authorities and incarcerated for a month. His father was told by a senior Omani officer they'd been contacted by a “foreign intelligence service” with a request to investigate the young man. The Omani police only asked Ghanem about his ties to the Calgary group.

Finally, he was told he must leave Oman. Because Canadian officials refused to renew his expired Canadian passport, Ghanem was forced to rely on his Algerian one. Ghanem flew to Algiers in May of last year where he was immediately detained by DSS, Algeria's secret police, and interrogated for a week at their headquarters. Again he was asked about his Canadian friends. He was then remanded to a crowded cell at the El-Harrach prison. “There is no doubt in my mind he was there as a result of information provided by CSIS to their Algerian counterparts,” says Caroline.

Ghanem was then charged with being affiliated with a foreign terrorist group, facing a possible 20 years in prison. Ghanem has since told the CBC he was tortured while in custody. “He was in a cell with about 75 other men, half of whom had beds and half of them who slept on the concrete floor,” says Caroline. “There was one large room and there was one shower head in the room… and there was a hole in the ground below the shower as the toilet for the entire group. Conditions in the prison were pretty atrocious, the food was inedible.”

This past June, Ghanem went on trial in Algiers, which lasted one day. No evidence was produced by the prosecution. He was released and returned home to Canada and is now living in a major city. “He was sort of rendered on the cheap,” says Caroline. “The information (CSIS was seeking) was all old, it was stale stuff.”

Yet CSIS and RCMP not only arrange to have Canadians arrested overseas – they entrap them in Canada in so-called “terrorist” schemes too.

Next in this National Observer four-part series: How CSIS and RCMP fabricate “terrorist” plots

Surely all a Canadian citizen

Surely all a Canadian citizen should need to enter Canada is proof of citizenship. A passport, even an expired one should be sufficient. An airline should not be allowed to deny one passage to Canada because the Canafian passport is expired. This get complicated if there is no direct flight to Canada; in this case the Canadian government should be required to issue a travel document.

Comments