Support journalism that lights the way through the climate crisis

Last week, the federal government made some major changes to the carbon tax. The surprise announcement has set climate policy in Canada in turmoil. But there was a silver lining in the announcement that may hold the key to unlocking cost and climate benefits for Canadians.

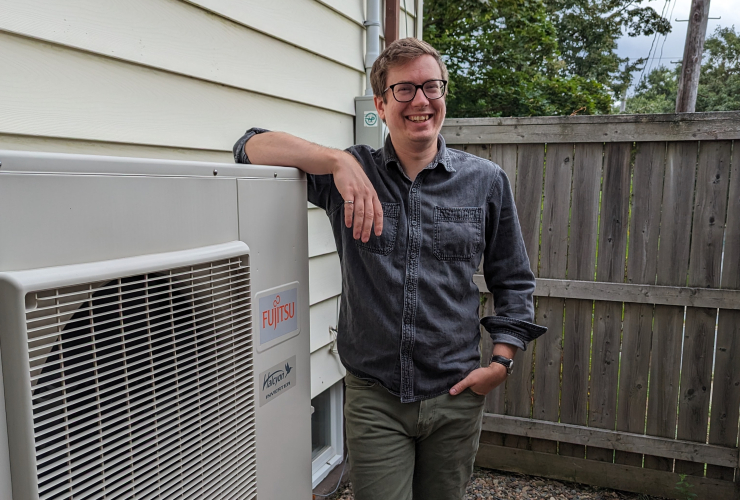

The announcement included additional funding to help Canadians make the switch from heating oil to heat pumps. Modifications to the Oil to Heat Pump Affordability Program will raise the maximum federal funding for eligible homeowners installing a heat pump from $10,000 to $15,000.

This program is Canada’s only policy that helps low- to moderate-income households access energy efficiency services. By expanding it, the government acknowledged the crucial role of energy efficiency in permanently reducing energy costs for countless Canadians struggling with high bills.

Energy efficiency upgrades are a proven way to lower energy bills, locking in savings over time. It creates good jobs, conserves energy, offers protection from cold and extreme weather events and improves health and housing quality for those struggling to meet their home energy needs. Providing energy-efficient homes to all Canadians, including renters, is critical to addressing these energy affordability concerns and reducing emissions to achieve Canada’s climate goals.

The announcement didn’t go far enough, restricting the program to homeowners in Atlantic Canada heating with a single fuel type. Without a truly national low-income energy efficiency strategy, millions of Canadians will continue to be left behind.

But energy efficiency can rescue federal climate policy. Here are four things the government could announce that would lower emissions while saving Canadians countless dollars on home heating costs:

- Expanding to include all fuel types: The heat pump program announced for Atlantic Canada does remove some barriers for oil-heated homes, yet only three per cent of Canadian homes heat with oil. Most Canadians heat with natural gas or electricity, and low-income Canadians struggle to pay those bills, too. We must expand the program to ensure inclusivity and accessibility.

- Creating whole-home, no-cost, turnkey upgrades: Not everyone can cover the upfront costs or take on debt, which means the vast majority of low- to moderate-income homeowners and renters in Canada are receiving no energy efficiency support from the federal government. Existing provincial and utility programs are delivering whole-home, no-cost, turnkey upgrades, but are constrained in their depth and reach. A federal heat pump program can make these existing programs more holistic, reach more homes, deliver more savings and reduce emissions. Homes can be made healthier and safer with federal support, introducing measures to aid in mould remediation and replacing hazardous electrical wiring.

- Targeting hard-to-reach communities: Federal programs can include social supports for workforce development and community partnerships to ensure the benefits of energy efficiency reach traditionally marginalized communities. Through these supports, trust can be built, awareness can be raised and we can ensure no one is left behind.

- Securing tenant protections: A third of Canadians rent and efficiency programs are leaving these individuals behind. By investing in and enhancing tenant supports, the federal government could address this inequity and lead the way in ensuring renters also benefit from a clean and efficient future. Efficiency Canada’s report Energy Efficiency in Rental Housing addresses policy mixes for efficient, affordable and secure housing.

Making sure everyone can secure energy efficiency solutions for their homes can be an affordability-enhancing climate solution for all of Canada. It starts with a national program focused on low- to moderate-income needs.

Canada will not be alone in prioritizing low-income energy efficiency. In the United States, the Weatherization Assistance Program has been upgrading low-income homes since the 1970s.

As the weather gets colder, let’s make sure all Canadians can save energy, regardless of their income level, where they live, or the fuel they use for heat. Given the double pressures of climate change and the cost of living, there is no better time for policymakers to support low-income energy efficiency across Canada. That is something the government has the ability to do, and something we hope to see next time there is a surprise announcement.

Abhilash (Abhi) Kantamneni is an Efficiency Canada research manager specializing in energy poverty and low-income energy efficiency.

"Federal programs can include

"Federal programs can include social supports for workforce development and community partnerships..."

On this specific topic, a timely RAP webinar (Regulatory Assistance Project) is scheduled for next Tuesday:

Topic - Getting the Job Done: Models for Heat Pump Workforce Development

Nov 7, 2023 2:00 PM ET

Info & reg'n:

https://reurt-zgpvh.maillist-manage.net/click/18d887330a481ef/18d887330a...

This webinar appears to be coming from the USA. It's free, and open to all, globally.

These are excellent webinars, in my experience.

What is RAP?: https://www.raponline.org/

Additional upcoming webinars and >15 years of archives to learn from:

https://www.leonardo-energy.org/

I can't overstate the value of these resources.

A few observations.

A few observations.

The author makes excellent points and, given their occupation, the incessant framing around efficiency makes sense. Nonetheless, it wouldn’t hurt to broaden the keyword choice from only “energy efficiency” to include “cost” and “climate” not to mention additional benefits of demand-side management.

Aside: I’d also like to see, from everyone in this space, some rhetoric that suggests that energy – from whatever source – WILL get more expensive (per unit) in the future, so efforts to reduce personal demand will have additional and ongoing personal benefits. Instead, what we hear is that electricity WILL always be cheap “and that’s a good thing”. (Bollocks)

On the question of who pays for upgrades…

While I agree it is vital to provide collective assistance (i.e. gov’t money) where needed to ensure everyone is safe from being Frozen or Fried – ForF(?) – in their homes, there need to be considered limits:

1. on what homes qualify (let me quickly slap together a clapboard shack then apply for free money to actually complete the build!). If a specific building was so poorly constructed or maintained that it made no sense to spend any money to upgrade, then what?

2. On how much $$ is granted vs a loan. On this, I’d like to see consideration of low-payment loans tied to a property that remain until the loan is paid off. Such a loan is against the property and not the property owner and, therefore, need not be discharged on the sale.

If a single, whole-home upgrade were to cost $100,000 dollars, to pick an example number, can you imagine the national budget implications?

The author spoke only about heating (it’s that time of year) but cooling is equally important.

Last thing, there is no mention of:

1. A construction workforce beyond heat pumps. We need an expanded workforce to provide all the upgrades plus all the new construction that we need.

2. New building codes so that brand-new builds don’t immediately, or foreseeably, require energy-demand reducing upgrades. We need “leapfrog” code makeovers. And we need them yesterday.

3. In concert with code overhauls, we need overhauls of zoning, not to enrich developers (a standard motivation), but to reduce aggregate energy demand – not to mention reduced land use -- in our built environment. The days of low-density R1 must end.

1/2

1/2

A few bservations.

The author makes excellent points and, given their occupation, the incessant framing around efficiency makes sense. Nonetheless, it wouldn’t hurt to broaden the keyword choice from only “energy efficiency” to include “cost” and “climate” not to mention additional benefits of demand-side management.

Aside: I’d also like to see, from everyone in this space, some rhetoric that suggests that energy – from whatever source – WILL get more expensive (per unit) in the future, so efforts to reduce personal demand will have additional and ongoing personal benefits. Instead, what we hear is that electricity WILL always be cheap “and that’s a good thing”. (Bollocks)

cont...

2/2

2/2

On the question of who pays for upgrades…

While I agree it is vital to provide collective assistance (i.e. gov’t money) where needed to ensure everyone is safe from being Frozen or Fried – ForF(?) – in their homes, there need to be considered limits:

1. on what homes qualify (let me quickly slap together a clapboard shack then apply for free money to actually complete the build!). If a specific building was so poorly constructed or maintained that it made no sense to spend any money to upgrade, then what?

2. On how much $$ is granted vs a loan. On this, I’d like to see consideration of low-payment loans tied to a property that remain until the loan is paid off. Such a loan is against the property and not the property owner and, therefore, need not be discharged on the sale.

If a single, whole-home upgrade were to cost $100,000 dollars, to pick an example number, can you imagine the national budget implications?

The author spoke only about heating (it’s that time of year) but cooling is equally important.

Last thing, there is no mention of:

1. A construction workforce beyond heat pumps. We need an expanded workforce to provide all the upgrades plus all the new construction that we need.

2. New building codes so that brand-new builds don’t immediately, or foreseeably, require energy-demand reducing upgrades. We need “leapfrog” code makeovers. And we need them yesterday.

3. In concert with code overhauls, we need overhauls of zoning, not to enrich developers (a standard motivation), but to reduce aggregate energy demand – not to mention reduced land use -- in our built environment. The days of low-density R1 must end (which does not mean high-rises, or even >3 storeys, everywhere).

Comments