When Husky Energy officials showed up more than 40 minutes late to an emergency meeting with the James Smith Cree Nation, the band members thought it was rude.

When an unknown advisor was sent instead of the company's own manager of aboriginal and community relations, the elders though it was "appalling." But when a Husky official told the entire Indigenous community — whose territory may be poisoned by its catastrophic oil spill — to wait until Monday for answers, it was more than Chief Wally Burns could handle.

"In my heart, I think this meeting was just a waste of my time," he told National Observer, frustrated after a two-hour consultation with Husky Energy on Thursday evening. “You know the sad thing about it? We can’t wait until Monday because the river is going to come up four feet, and when it goes down it will have environmental impacts.”

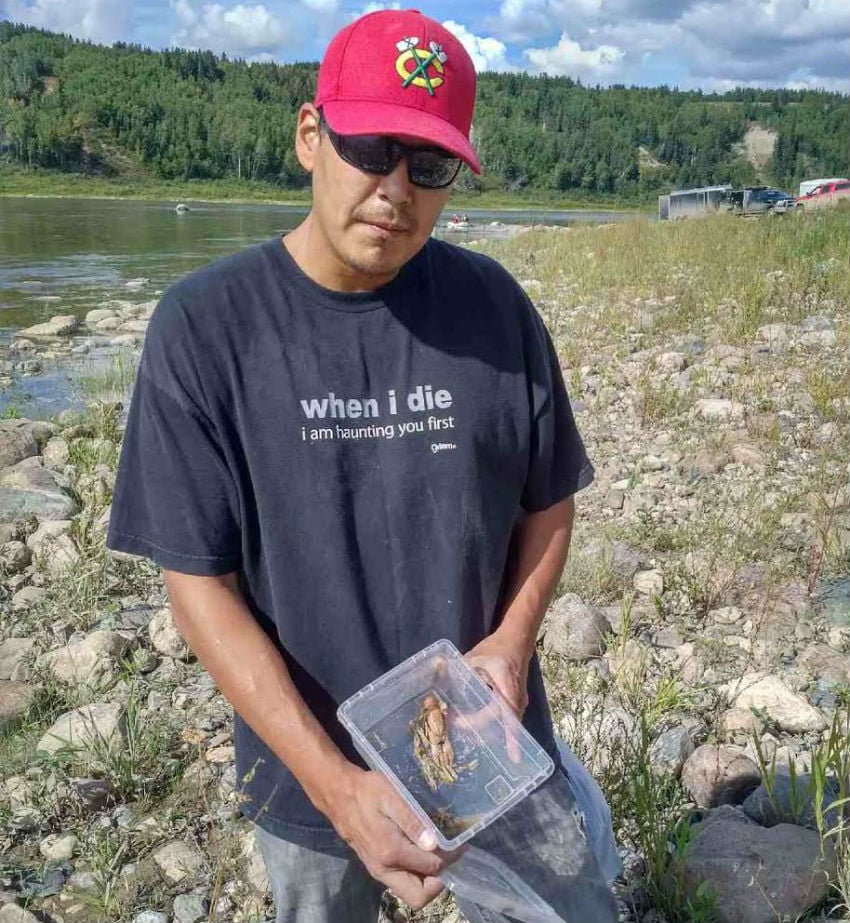

Since early August, the James Smith Cree Nation has found foam and oil washed up on the shores of the North Saskatchewan River, which runs right through its territory in the heart of the province. Dead crayfish litter its river banks, and all of the summer wildlife — butterflies, grasshoppers, frogs, and more — have disappeared.

The chiefs are certain the damage spawns from Husky's devastating pipeline leak on July 21, which spilled more than 200,000 litres (roughly 1,570 barrels) into the North Saskatchewan River, prompting emergency water restrictions in several municipalities and killing more than 140 animals. But the First Nation has already depleted its $17,000 budget for flood mitigation on its own spill response, including independent water quality testing and the deployment of booms.

Asked when the community could expect some help from Husky however, Todd Belot, senior advisor for aboriginal and community relations, responded:

"Chief, I will go to the people that I report to and I will… today is Thursday… Monday."

"You're going to foot the bill"

The response came after a short, but impassioned speech from Belot promising that Husky's actions will speak for the company, and serve as proof of how well it has listened to First Nations concerns. Chief Burns couldn't believe the contradiction, or that the Calgary-based energy company didn't have anyone working over the weekend during a crisis who could help his community with oil containment.

And with the North Saskatchewan River expected to rise up to two metres over the weekend as a result of heavy rainfall flows stemming from Alberta, he said waiting until Monday wasn't a luxury they could afford.

"There's lots of talk but no answers," he told Belot. "We're putting our foot down... You’re going to foot the bill, it’s not our mess. We’re doing our best to clean up Mother Earth. Polluters pay, not dictate. That’s my message loud and clear."

Belot could not be reached for comment on this story, and Husky Energy's spokesperson, Mel Duvall, would not even confirm that the meeting took place. He stopped returning National Observer's messages two days after it published an article that found gaps in Husky's spill timeline, exposed the industry-friendly consultant it hired to analyze its water quality testing, and revealed the plight of the James Smith Cree Nation.

As of Wednesday, Husky would not confirm that it had ever met with Indigenous community, been made aware of its concerns, or had a meeting with the chiefs scheduled for Thursday. Yet according to Chief Burns, he has been in touch with Husky since early August, when the company requested that he send them a proposal to deal with spill containment in the territory — a proposal he promptly returned.

The only response Husky gave National Observer on the subject of the oil in James Smith's territory was that it may not in fact be from its pipeline.

Oil in river may not be from spill, says Husky

"It is not uncommon to see foam on the river, particularly during storms and high river conditions," Duvall said in a Wednesday email. "This has been stated many times before."

While the Saskatchewan Ministry of Environment confirmed that it knew the James Smith Cree Nation had found oil in its waters, it too, hesitated to link that oil with Husky's pipeline leak, the cause of which remains under investigation:

"It is important remember to visual sighting of sheen and foam may or may not necessarily have been caused by oil spill," said ministry communications consultant Ron Podbielski in an email. "These occurrences can form on any open waterbody under natural conditions or from other localized activities such as boating, pumping, or other discharges."

Saskatchewan's Water Security Agency has already taken water samples from the nation's portion of the river, but did not respond to National Observer's questions about whether it detected any contamination in time for publication of this story. The province did provide initial assistance with setting up spill containment, said Burns, but has not provided any financial compensation.

The First Nation's elders, who have been fishing, swimming, and boating in the river for decades, were deeply insulted by suggestions that the oil might not have come from Husky, and Estelle Hjertaas, a lawyer and environmentalist based in Prince Albert, Sask. — a municipality that has declared a local state of emergency as a result of the spill — agreed that the oil was likely from the pipeline.

"I think given that there was visible oil slick on the water, followed by foam, followed by visible oil the day after that on the water again, at a time when no one was allowed on the river at that point — it seems unlikely that the oil would come from other sources," she told National Observer. "It's possible there was a spill from something else, but it seems unlikely that it would be in the quantity that we're seeing and reporting, especially in the context that the oil spill just happened and its movement down the river was fairly well-documented."

James Smith Cree Nation has barred both the energy company and the ministry from entering its territories without explicit permission from the band office.

Elder Alvin Moostoos of the James Smith Cree Nation in Saskatchewan outlines environmental damage to his community as a result of Husky Energy's oil spill in the North Saskatchewan River on July 21, 2016. Video supplied by the James Smith Cree Nation.

Province not concerned about food chain

In the meantime, Chief Burns has told his community not to eat fish from their territory, and the provincial government has issued a precautionary “do not consume” fish advisory for the entire North Saskatchewan River. While Water Security Agency updates indicate that the river may be safe to drink from again (only one contaminated sample came back from recent surfacing testing), the waterway remains hazardous for most aquatic wildlife.

During their meeting with Husky on Thursday, which was attended by James Smith Cree Nation leaders and representatives from Indigenous communities further downstream, elders outlined their concern that contamination could move up the food chain through mammals drinking from the river or eating poisoned fish and crayfish. While Husky "acknowledged" these concerns, the Ministry of Environment said it wasn't too worried:

"Other species that are not living in water will have a significantly different and higher level of tolerance to the level of compounds founds in the water," Podbielski explained via email. "This is why aquatic tolerances, which are lower and different than human tolerances, are being tracked and recorded in the testing. Based on the scientific evaluation to date, the Ministry has concluded the concentrations found in exceedance samples do not warrant an advisory for wildlife consumption at this time."

Members of the James Smith Cree Nation however, have already seen animal tracks leading away from river, indicating that bigger animals are either drinking from it or eating the dead crayfish they are certain are toxic. They also voiced concerns about the endangered sturgeon population that lives and spawns in the North Saskatchewan River, but the ministry confirmed that no sturgeon have been reported dead as a result of the spill.

Hjertaas, however, was hesitant to trust any impacted wildlife statistics churned out by Husky or the provincial government.

"My biggest concern with the numbers is that it’s being reported on as though the total number of animals that died is 144 animals, which is not correct, because that’s the number of animals that the government is aware of that died, not the total number impacted by the spill," she explained. "It's a mischaracterization of the information that we do know."

More questions about Husky's numbers

According to the ministry, 10 birds, 31 waterfowl, 50 small mammals, two reptiles, 38 fish and 13 crustaceans have been killed, and 52.7 per cent of impacted shore line has been cleaned. As of Aug. 22, Husky reported that 47 per cent of the shoreline had been cleaned, but would not confirm with National Observer how it arrived at this statistic.

While the Ministry of Environment confirmed that it based its percentage on cleanup taking place roughly 117 kilometres downstream of the initial pipeline leak near Maidstone, Sask. — an area that most certainly doesn't include the shores of the James Smith Cree Nation — Husky Energy has refused to provide National Observer with similar information on how it makes the calculations delivered in its public updates.

Comments