There are no two ways about it, according to German political scientist Arne Jungjohann: if you want to make meaningful progress on climate change, you have to get big money out of politics.

“Then you get fossil fuel money out of politics,” said the author and energy analyst. “It’s very, very important to make this a non-partisan issue, otherwise you cannot create this stability and certainty that is needed for the investment people.”

Jungjohann, an advisor to the German Green Party, spoke at a clean energy discussion in Ottawa last week hosted by National Observer and the German embassy. Other guest speakers at the standing room-only event included Helmut Herold, CEO for Senvion, Edmonton-Strathcona MP Linda Duncan, and Clare Demerse of Clean Energy Canada.

Jungjohann offered “lessons" from the German clean energy story, also called the Energiewende. It’s the German word for the country’s clean energy transition, and Jungjohann co-wrote a book about it: Energy Democracy — Germany’s Energiewende to Renewables.

If Canada has anything to learn from Germany's Energiewende, he said, it's that corporate money must exit the equation, citizens must be involved early on, and clean energy must become non-partisan. He called it the "democratization" of clean energy.

"If you are an energy company in Germany, and you know there’s an election coming up, there are some things at stake, but you know that after the election, no matter who governs, there won’t be a 180-degree reverse of course," he explained.

Over the last decade, Germany has emerged as a clear leader in the fight against climate change and the race to a world where renewable energy reigns supreme.

Citizen-owned renewable power

Germany doesn’t have ideal conditions for renewable energy, said Jungjohann. The country is about as “sunny as Alaska,” he joked, yet there have been days when wind and solar energy output has been so high, it supplied nearly 100 per cent of the entire country’s energy demand.

Roughly 33 per cent of Germany’s electricity is renewable, he added, and German citizens at one point own 47 per cent of the country’s renewable energy through private installations, cooperatives and community projects.

He's often asked how Germans got utility companies to accept citizen-owned renewable energy, but the short answer is: they didn't. Over the years, he said utility companies have resisted "new technology" that compromises their traditional energy assets.

"The real question is, how did Germans convince politicians to pass laws that would allow citizen energy?” he said.

Jungjohann described three "junctions" in German history that changed the Energiewende forever. If an industrialized country like Germany can meet nearly all of its energy needs through renewables, he added, almost anybody can.

The junctions of the Energiewende

In the early 1990s, the idea of "citizen-owned" energy was unpopular, said Jungjohann. It was unpopular within the utility companies, who wanted to protect their business, and it was unpopular in Parliament, where only a handful of politicians wanted to make a transition to cleaner energy.

But East Germany and West Germany were on the brink of unification, he explained, and the utilities companies were distracted by what the merge would mean for their power centres.

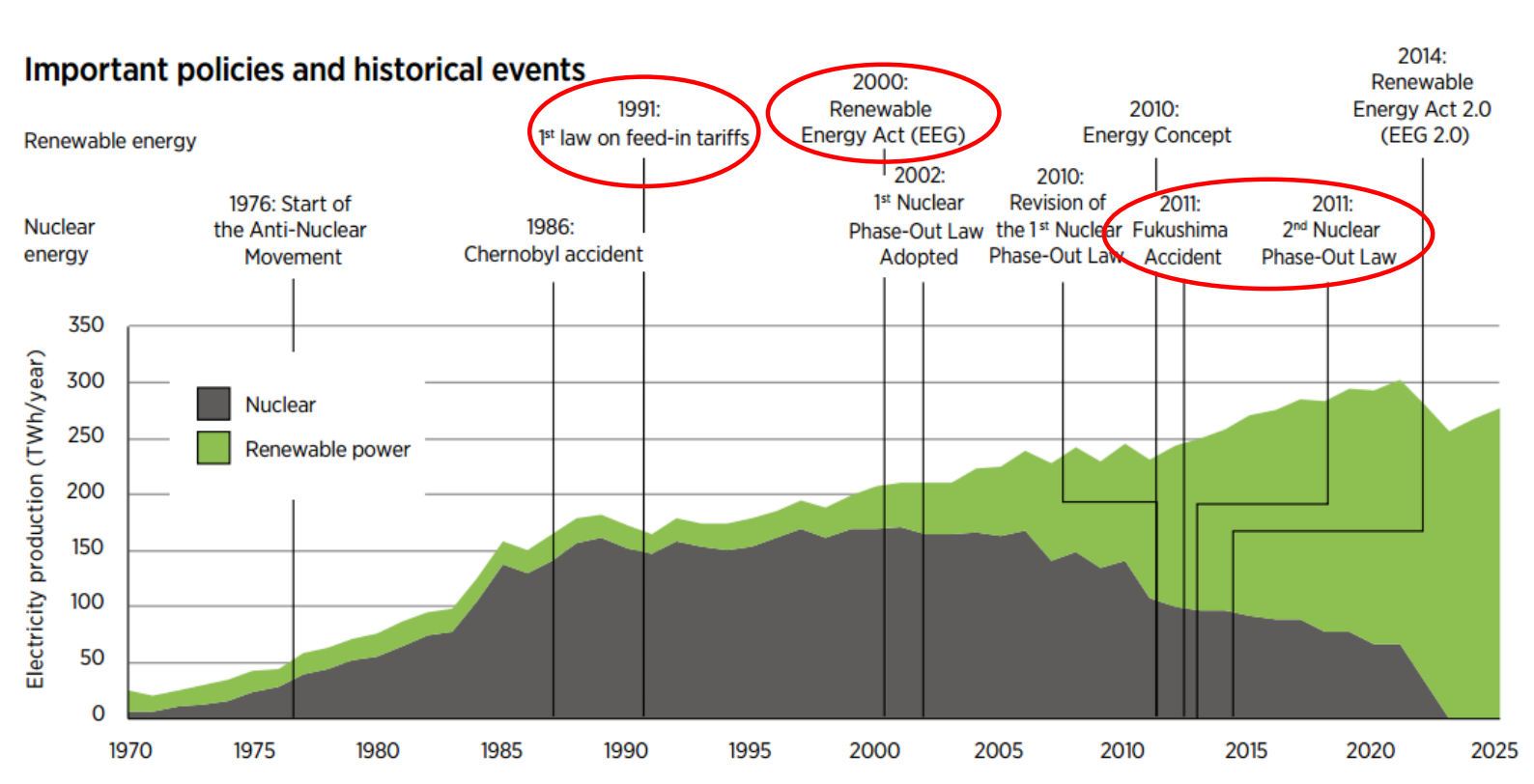

As Jungjohann tells it, the opportunity was taken to obtain passage of renewable energy legislation in Parliament “under the radar.” In 1991, Parliament approved the first law to bring electricity from renewable energy sources onto the public grid, opening the window for German citizens to participate by installing solar panels on their roofs, among other projects.

The second junction came 10 years later, said Jungjohann.

By 1998, skyrocketing unemployment rates had pushed the Social Democratic Party of Germany and the German Green Party into a historic coalition. Their alliance disrupted the traditionally strong ties between utility companies and the federal government, he explained, creating another opportunity to push clean energy legislation through Parliament unnoticed.

The utility companies were busy with “other fish to fry,” he said, as politicians crafted the Renewable Energy Resources Act, which came into force on April 1, 2000. A strengthened version of its 1991 predecessor, it granted priority to renewable energy sources through tax reform on electricity and natural gas.

A shock to the system came a decade later, in what Jungjohann describes as the third and final junction: on March 11, 2011, a 15-metre tsunami disabled the systems of the Fukushima Daiichi plant in Japan, leading to a massive nuclear meltdown. Watching the disaster on TV, he said, German Chancellor Angela Merkel realized that a nuclear legacy in Germany was no longer possible.

“With very important state elections coming up, she decided to reverse her party's long-held position,” he told an audience of concerned citizens, MPs, and business representatives in Ottawa.

“That summer of 2011, a historic vote sealed that the nuclear industry would end its business in Germany for good.”

The last nuclear power plant in Germany will shut down in 2023. Today, the country is one of three in all of Europe whose policies are on track to keep global warming below two degrees this century.

The "democratization" of clean energy

So what can Canada take away from Germany's Energiewende?

There is no “silver bullet” for clean energy, said Jungjohann. Careful timing, patience, political will, and a broad range of policies and frameworks are necessary. As evidenced in the German example, he added, the clean energy transition must be non-partisan to create financial stability.

It's a technical transition from fossil fuel-based energy to renewable energy, he explained, but it's also a political and cultural transition; it's a transition from centralized, corporation-dominated energy, to a smaller, decentralized power grid.

In the end, he added, the Energiewende helped create more than 350,000 jobs in the renewable energy sector and dramatically reduced the cost of citizen-owned, renewable power. Solar power today is twice as expensive in the United States as it is Germany.

"Renewables are winning the cost race, in some places faster than others," said Jungjohann. "But one thing is also clear: without rules that allow citizens to take part in this rally, it will be corporations that organize this transition for us and without us."

Comments