As Canada prepares to observe 150 years of Confederation, it’s clear that celebratory rhetoric doesn’t square with the country’s treatment of Indigenous people and their women in particular.

We are a country of two solitudes. As colonizers—guests in this country—we are preparing the celebrate the genocide of a beautiful people.

On life support—with dwindling grassroots endorsement, no coherent plan, a ticking clock, and inconsistent focus—Canada’s national inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) lurches toward an inevitable request for more time and money.

But time isn’t only what’s needed, and neither is an increase to the $53.8 million already allotted for the two-year commission destined to submit its report to the government by the end of 2018.

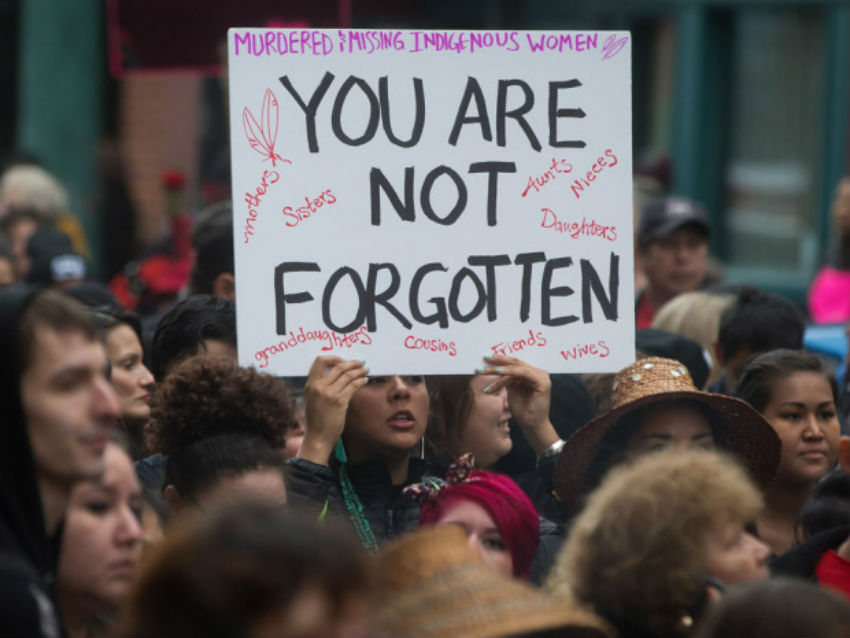

Massive change is required to alter the reality that Indigenous women and girls comprise only three per cent of Canada’s population, but make up 10 per cent of Canada’s homicides; a tall order for any inquiry. They continue to die.

It’s time for a hard reset on the national MMIWG inquiry.

Trudeau faces a difficult choice

Intentions appeared noble back in September 2016, when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government announced plans for the inquiry in direct response to insistent cries to end the MMIWG tragedy. The weight of years of dashed hopes and the unmet expectations of families and inquiry advocates has all but ensured no amount of effort from this inquiry will be enough.

Its spinning wheels have made the taste of disappointment all the more bitter.

Trudeau faces a difficult choice: announce a shift in the inquiry’s structure now and weather the I-told-you-so’s from fiscally conservative critics of the inquiry, or allow the train wreck to continue until it inevitably crashes into the growing pile of his administration’s failed promises to Indigenous people ahead of a 2019 federal election.

Neither option will sit well with anyone if it involves an increase in financial support to a struggling and unproven inquiry or an indication this tragedy will not be halted. For Conservatives, it adds fuel to the Liberals-spend-too-much-on-ineffective-programs fire while inquiry supporters and Indigenous advocates—not all currently on the same team—will see it as yet another blanket-wearing Trudeau photo op lacking any meaningful change or improvement to Indigenous lives.

It’s hard to square $500 million for a July 1 party with a $53.8-million investment in stopping the crisis of MMIWG.

Good intentions gone awry?

Perhaps I’m naïve, but I don’t believe this inquiry was intentioned or destined to fail. I would imagine large-hearted Canadian Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Carolyn Bennett is rolling over in her Parliamentary seat watching this inquiry she so painstakingly laid the foundation for flounder.

We sat together on a ‘Women in the World Summit’ panel in New York City in April 2016 entitled ‘Canada’s Shame’ and discussed the issue at length in front of an international audience. Her commitment to Indigenous people is palpable—does her government share that commitment? There are Indigenous people who have left the inquiry or are considering doing so because of dysfunction and internal strife—none of them have made this choice lightly.

Knowing first-hand the amount of effort, emotion, and passion Bennett put into making this inquiry a reality, she must feel downright sick, wondering if she wasn’t merely canon fodder in a strategy to make the Liberals appear sensitive to the plight of Indigenous women, while effecting no change to their dire circumstances. Family members and activists tell me they feel the same way.

We see this selling out of promises in the name of political gamesmanship playing out in other areas of the Liberal’s Indigenous file, so it’s easy to imagine. As with the inquiry, I still believe the Liberals—the party I voted for—would like to do the right thing, but they are off course and off message right now.

The optics of a government—or someone like me—stepping in and dictating a change in course to an independent commission led by Indigenous commissioners is undoubtedly something both Trudeau and Bennett desperately wish to avoid. I’m not suggesting the issues plaguing this inquiry have anything to do with Indigenous leadership, quite the contrary. I am suggesting they haven’t been equipped to succeed. Sounds a little like efforts at Indigenous self-government, doesn’t it?

Let Indigenous peoples take the helm

The Indigenous community is far more skilled, educated, diverse, and multi-faceted than many non-Native Canadians understand. Stereotypes continue to frame non-Native ideas of Indigenous peoples. Give this inquiry over to Indigenous people at the grassroots level. Let the people on the ground—many of them lawyers— write the terms of reference. Let them define the problem and what’s needed. They know better than the rest of us do.

Immediately after the terms of reference were leaked ahead of the inquiry’s announcement—an ominous harbinger of things to come—many felt the timeline was too tight to adequately study and make recommendations on far-reaching issues affecting Indigenous women in Canada such as violence, poverty, racism, substance misuse, and housing.

Others worried the mandate did not allow for proper examination of the role of police incompetence and indifference in the tragedy. This was the first communication roadblock the inquiry faced when families and activists raised concern over the lack of language in the leaked terms of reference outlining how police would participate in the proceedings, and what power—if any—could compel that institution to co-operate in a potential critique of their performance.

I must disclose that I have had several conversations with the inquiry dealing with the issue of police accountability. We acknowledged the delicacy of placing police on the defensive and the very real problem of the stonewalling tactics such as limiting disclosure of information, a strategy they will employ if they feel threatened—and police always feel threatened. These conversations showed me that inquiry staff understands the challenges they face.

I advised the inquiry that if the police don’t want them to know that certain documentation exists, they won’t volunteer it and there are few mechanisms compelling them to. The RCMP will not voluntarily do anything that risks placing them in a bad light. Obviously, to communicate this reality to family members and activists would also put police on notice that they will be closely scrutinized, despite the absence of language in the terms of reference. I felt the Inquiry staff understood and were prepared to navigate this issue.

In our conversations, I found inquiry lawyers and commissioners to be aware of the scope of the job. They are smart, thoughtful, and deeply committed to the success of the MMIWG inquiry. Each person I have met with is profoundly dedicated to saving lives. I also found them overwhelmed and struggling to focus on what were the most critical out of many pressing priorities. From what little I am privy to, I sense they lack a cohesive plan. More is needed than hearts in the right place.

Who is this inquiry for, if not for them?

I have no intention of speaking for Indigenous families and activists, I simply wish to add my voice to theirs, stand beside them, and support their concerns as they have previously expressed, based on my experience with this file. I volunteered to speak with the inquiry because I had no interest in testifying before another commission, but I wanted to offer whatever help I could.

As a former police officer familiar with these cases, I admit to feeling like a sucker, a sentiment shared by so many testimony-fatigued family members of the victims of these tragedies. Like those families and activists, I hoped that this time, it might be different. Maybe this time, telling their stories would lead to change, would make a difference.

But only the hopeful survivors of this decades-long ordeal are participating, the people who still have a little bit of gas left in the tank for the emotionally roiling work of testifying in an inquiry, no matter how culturally sensitive or how many psychologists at the ready to offer trauma counselling.

Some have told me that simply agonizing over the decision to participate has left them feeling re-traumatized after enduring the disappointment and disgust of B.C.’s farcical Missing Women’s Commission of Inquiry in 2011-2012. I personally know three family members whose mental health has declined significantly since cracks in this inquiry became apparent. We must ask: who is this inquiry for if not them?

The MMIWG Inquiry’s website lists three goals for the commission:

- Finding the truth

- Honouring the truth

- Giving life to the truth as a path to healing

We know the truth. Far too many—more than 4,000 by some reports—valued and cherished women and girls have disappeared and been killed. This continues today. These are human beings.

Police indifference and racism has been the rule, not the exception in investigating these cases. Canada’s racist, colonial history—culminating in the implementation of Indigenous residential schools—stole generations of people, leaving them searching for their culture and identity.

Housing for Indigenous peoples and communities is desperately needed, both on and off reserve. Social programs, education, and poverty-reduction strategies are desperately needed. The $53.8 million investment could offer a good start, and any extensions and the accompanying budget hikes this inquiry will require could further assist this resuscitation of Indigenous lives rather than end up squandered by administrative bungling and misguided focus.

Here are some of my suggestions for change, acknowledging my white privilege and that my ideas are only intended as an offering.

1. Take the Politics Out of It

No, you can never remove politics. However, divide the MMIWG inquiry into several working groups led by Indigenous leaders, predominantly female.

Staff the groups with qualified Indigenous experts. There are many, many out there. Support the experts who are there now or who have already resigned because they saw the writing on the wall early on.

Consult the Indigenous community on who they would choose. Where is Cindy Blackstock? Pam Palmeter? Bev Jacobs? Christi Belcourt? Senator Murray Sinclair led the TRC and wrote the book on running effective inquiries—has anyone listened? Allot money as needed, with a cap subject to periodic review.

2. Acknowledge that a multi-pronged approach is needed

The inquiry is struggling with where to focus its energies. Form several working groups. All groups will intersect to a large extent because of the historic nature of the causes of the MMIWG crisis.

One set of groups could work to find present day solutions to issues on and off reserves such as violence against women, poverty reduction, housing, youth suicide, family violence, and addiction. All of these issues place Indigenous women in the crosshairs of predators.

The second set of groups could look at the disproportionate number of Indigenous people represented in the justice system and the need for educating non-Native Canadians on Indigenous history, all through the lens of colonialism and its far-reaching racist impact.

All groups could work toward the goal of stopping this MMIWG tragedy from continuing. The working groups above would deal with the historic reasons this crisis has come to be a national epidemic and find solutions to changing attitudes toward Indigenous women and the conditions they presently live in which subject them to violence.

Another arm could form investigative teams to conduct a survey of MMWIG cases with the goal of creating policy and accountability for police and the justice system, ensuring any new cases are handled appropriately. Currently, this is handled in a piecemeal fashion, with some families receiving help while others wait for any communication from an over-tasked inquiry.

Individual cases must be reinvestigated. The Ministry of Public Safety should take over this task, overseeing the creation and efforts of an independent civilian team, armed with legislative tools to compel police accountability and co-operation—with consequences for non-compliance.

This team could assist families with requests to open their loved ones’ files—police and coroner service—to them, allowing them to see anything that is not considered private for the victim or sensitive investigative hold back information. What is considered sensitive, why, and by whose determination must also be scrutinized. Families cannot compel this type of information on their own and their voices and concerns go unheard.

3. Create a tribunal to document family stories

It is common practice for teams of researchers and psychologists to travel to war-torn countries and hear and document survivor stories through narrative inquiry. Traumatized people are able to tell of their experiences to researchers in safe and supportive environments with counselling provided.

As with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), which examined the horrific Indian residential school system, the stories could and should be compiled to form a lasting legacy of the intergenerational pain and suffering caused by the MMIWG crisis. Indigenous researchers and counsellors should be steering this and all of the other initiatives I’m proposing.

Knowing their stories are forming a permanent chronology of the tragedy—incorporating the principles of Indigenous story work—would help to assure family members this is not just another unsatisfying and traumatic retelling of their story with no purpose.

The TRC required many years, and several changes in commissioners and focus before completing a far-reaching and culturally important document. This report is a blueprint for all non-Native Canadians and Indigenous people of a dark time in our history and a path to healing. The 94 recommendations presented offer tools for change, for reconciliation.

The national MMIWG inquiry must be reset now. Unlike the residential schools issue, Indigenous women and girls are still disappearing and being murdered almost daily across this country, even as many people celebrate Canada’s 150th anniversary. It’s time for this tragedy to end. Only then will there be time for dancing.

Let’s give the MMIWG inquiry the transfusion and self-governance it needs to do the job.

— Lorimer Shenher is a former Vancouver Police detective and the author of ‘That Lonely Section of Hell: The Botched Investigation of a Serial Killer Who Almost Got Away’, his account of working on Vancouver’s Missing Women investigation. Lorimer holds an MA in Communications and writes on police accountability and social justice issues. He created the audio documentary ‘Where Did that Come From? Indigenous Activists Discuss the Creation of Canada’s National Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Inquiry’ which can be heard here.

Comments