Last fall, Greg Quachegan took 10 students hunting, an annual tradition at Dennis Franklin Cromarty (DFC) High School in Thunder Bay, Ont. They bagged a moose, and the vice-principal taught his students how to be on the land, hunt, fish and clean the animals.

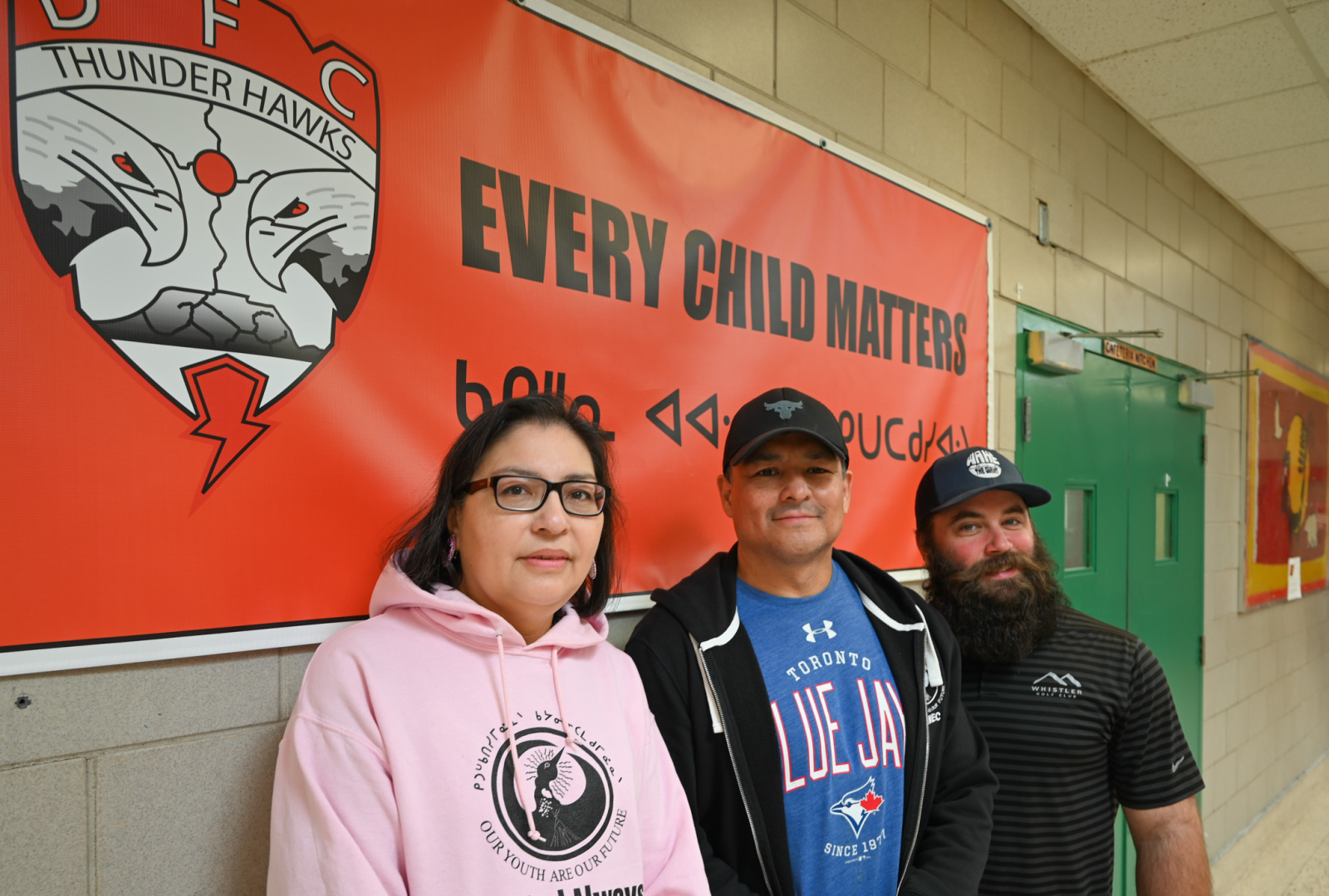

Land-based educator and school administrator are just two of the several hats Quachegan has worn at DFC, where Indigenous students come from across northern Ontario to receive a high school education, often from grades 9 to 12. For two decades, he has been in one role or another at the school, including as a teacher, boarding parent and school counsellor.

It’s common for staff to perform several roles at Indigenous high schools in Thunder Bay. Schools are often short-handed, and turnover can be high because salaries — cobbled together through federal tuition money, grants and other project-based funding from various government and non-profit organizations — are often lower than at schools funded directly by the province.

That shortfall takes its toll. Longtime grassroots staff, who serve First Nations students from the North because it is meaningful, are stretched thin from years of underfunding and under-resourcing. And though there have been some improvements, equal funding does not always mean equity for First Nations schools.

Funding for Indigenous schools handed out by the federal government reached parity with the rest of Canada after 2016. Today, these institutions receive $12,000 per student per year. But before, Indigenous schools were given $6,200 a year per student — roughly half of what provincially funded schools got and continue to receive, said Dobi-Dawn Frenette, education director for the Northern Nishnawbe Education Council, which operates DFC and its sister school Pelican Falls.

For over half their existence, the lack of funding at Indigenous schools in Thunder Bay left students grossly neglected compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts. For administrators, that shortfall has meant playing catchup where possible, chasing grants to deliver culturally specific programming or renovating decades-old buildings that were repurposed as school facilities.

Everything from curriculum development to psychologists, speech pathologists and subject-matter experts typically provided by provincial school boards and the Ministry of Education falls into the hands of small staffs working in Indigenous education. With little additional funding for higher-level services, schools are tasked with raising money to support such programs on their own, Frenette explained.

“The money’s not there, the services are not there,” Frenette said.

Chapter 1: Chasing funding means less face time with students

Staff at First Nation organizations are often just as stressed out as their students, dealing with the frustrations of a precarious, underfunded and under-resourced education system.

Take, for example, one meeting between Matawa Education Centre, which represents 12 First Nations in northern Ontario, and the provincial government. On the province’s side were 10 professionals: a lawyer, a policy analyst, an assistant, a researcher and so on. On Matawa’s side of the table was the principal, education director and student achievement officer — a visible disparity in the people power behind the school’s programming.

Matawa had to take on all those policy, assistant and researcher roles with limited staff, said Sharon Nate, the education director for Matawa Education.

After seven young Indigenous students were found dead in Thunder Bay between 2000 and 2011, a provincial inquest issued 145 recommendations to create safe conditions for students finishing their high school education. These included stable and adequate funding for DFC and Matawa Learning Centre, a new school and residence for DFC and a resource-sharing facility for Northern Nishnawbe Education Centre and Matawa Learning Centre.

A.J. Haapa, a history teacher by training, is now tasked with fulfilling the inquest recommendations at DFC. That includes building a new school and residence where students will learn and live in the same building.

It’s a demanding and strenuous role, and on top of that, he must also write endless grant proposals to the Ontario and federal governments and non-profit foundations to build up the school’s infrastructure, develop preliminary plans for a new school and create programs.

After class, he sometimes plays floor hockey and makes music with students in the school’s studio. During the year, he organizes the school’s Wake the Giant program, an allusion to Nanabijou, the sleeping giant who rests off the mainland of Thunder Bay. The program helps onboard students from the North and educates non-Indigenous citizens of Thunder Bay about Indigenous histories and cultures.

The program also includes a decal program for 400 local businesses, an online training module for businesses and an annual music festival that doubles as an orientation week. The festival this year will feature Deadmaus, Sara Kae and Ruby Waters. The artwork for the poster was done by DFC student Harmony Fiddler.

Haapa has become apt in his grant-writing role, securing a new outdoor basketball court and shop at DFC and a baseball field at Pelican Falls through public fundraising with the Toronto Raptors, local businesses and the Toronto Blue Jays. He sometimes dreams of returning to the classroom to focus on the students, but until the inquest recommendations are complete, his work is not done.

Chapter 2: The spectre of stable funding

Haapa hopes that one day, funding to meet Northern Nishnawbe Education Council’s objectives will move from dollars handed out for specific projects to a stable lump sum schools can draw from to meet a variety of needs. He’d like the council to control where its money is spent rather than abiding by the constraints of many initiatives overseen by Ottawa or Ontario, which Haapa says can hinder the comfort and success of students.

Stable funding would make First Nation education sustainable, Haapa said. Both DFC and Matawa Education Centre have lost several staff members because of the uncertain nature of working at a First Nations high school in Thunder Bay.

“How can you retain staff if they don't know if they have a job in September?” he asked.

Matawa Tribal Council deals with similar restraints at DFC, scraping by with a stretched “piecemeal” budget and operating under project constraints. Nate, the education director, has known nothing else.

“If you give me $10, I’ll stretch that as long as I can because that's the mindset I've been living in; that's my whole career.”

Roles at Matawa are constantly shifting. Recently, Matawa had to move its high school art teacher into a full-time administrative position to keep up with a Sisyphean stack of paperwork and chase project-based proposals, a punishing task that leaves staff stretched thin like an elastic about to break.

The mountains of paperwork detract from the essential work with students who need more support, resources and funding than the average high schooler because they move away from home at such an early age, Brad Battiston, principal for Matawa Education Centre, argues.

When it comes to funding, equality does not mean equity for First Nation students in the North.

“We're saying equality in terms of opportunity and service that meet the needs of our students,” Battiston said.

Chapter 3: Federal fiscal year pokes gaping holes in a stretched school budget

Every March, Indigenous high schools undertake fiscal gymnastics when funding dries up three months before the end of the school year.

Special education, for example, could screech to a halt if the school is unsuccessful in extending the funding beyond a one-year contract, Battiston said. Where provincial school boards often make plans for upwards of 15 years, it’s all Matawa can do to plan for one, he explained.

“How do you support a team of educators supporting at-risk youth… How do you support those kids not knowing what goes on beyond April 1?” said Brittany Kennedy, former art teacher and now full-time grant proposal writer for Matawa.

Battiston himself estimates he spends 70 to 75 per cent of his time on external administrative duties to keep the school running and prevent it from literally falling apart.

Take, for example, the building of the first gym at Matawa Education Centre, which has been in operation for 12 years. Until then, students had only small classroom spaces for gym class.

The school set forth to build its first-ever gym for $8 million before the pandemic, with funding from several programs and proposals. When the cost of building materials increased, Matawa had to cut out the bleachers. Meanwhile, a new gym was built at Churchill, a provincial school across from DFC, “in a matter of months,” Nate said.

It’s a similar feeling for Quachegan at DFC, who continues to work in a building with a leaking roof. He tells a story about a summer when the bedroom walls of his home near DFC constantly shook from the construction of the Thunder Bay District School Board’s new high school.

Being woken up by the shaking was a “slap in the face.” When he returned to work that fall and discovered the foundation of DFC had been damaged by the construction, he described that moment as a “kick in the you-know-what.”

Sometimes Nate gets asked what she would do if money was no object. She hates the question. It’s akin to asking: “What would you do if you won the lottery?”

“The only thing I would say is, it'd be a lot nicer to be more present with the students,” Battiston added.

“Nobody that I've ever known or heard of goes into education to be in government meetings.”

First Nations in the North face similar crises to bigger Canadian cities but, at times, at more acute rates. And students from the North arrive in the city carrying those burdens of colonial history in their duffel bags.

An opioid and meth crisis, a suicide crisis, a cost-of-living crisis and a housing crisis all stem from underinvestment and under-resourced communities living in the wake of residential schools and cultural dispossession. Combine that with a lack of social support and services, and students are left particularly vulnerable to the harm of these social crises, Nate said.

Without a strong support system around a student, leaving home can become a crisis in itself. Matawa has already lost three students this year to suicide and murder. Nate reckons there are few other principals in Ontario dealing with that level of loss.

“In southern Ontario? Probably none, you know.” Battiston has lost over 50 in his career, Nate said.

“We're trying, but we're also struggling.”

Thank you Matteo for these

Thank you Matteo for these important stories. In one of the richest countries in the whole of human history, it's astonishing and abominable that the under-funding of Indigenous schooling continues.

Comments