This story was originally published by High Country News and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

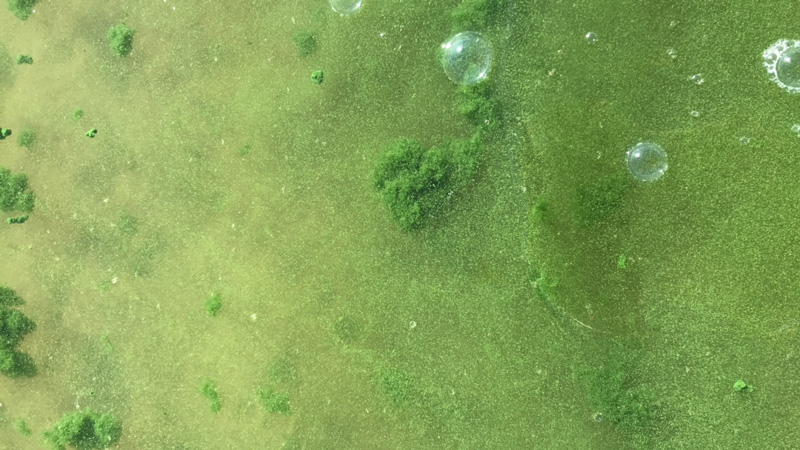

When harmful algae blooms spread across lakes, rivers and reservoirs, they sometimes resemble spilled paint or gobs of mucus — even grass clippings. Fuelled by heat and high levels of nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus, from wastewater discharge and fertilizer runoff, clusters of cyanobacteria produce toxins that can sicken people, pets, livestock and wildlife. Once a water body experiences its first harmful bloom, dormant bacterial cells linger, increasing the likelihood of another outbreak by orders of magnitude.

“Preventing these blooms in the first place is critical,” said Hannah Bonner, an environmental scientist with the Utah Division of Water Quality. “Both here in Utah and across the United States — we’ve got to stop this trajectory right now.”

This year, harmful algae blooms overtook 32 water bodies across Utah — the second-highest number since the state began monitoring — including Yuba Lake, Utah Lake and several reservoirs near Salt Lake City. Nutrient-rich runoff from last winter’s record rain and snowfall followed by extreme heat over the summer may have given the algae a boost. According to Bonner, most toxic blooms in Utah peak in August and September and then die out by late November. Many of the water bodies affected this year have already begun testing below danger thresholds. In recent years, however, warmer-than-usual temperatures have helped some blooms linger into winter.

Depending on the species of cyanobacteria involved, exposure to harmful algae blooms can cause skin rashes and, if ingested, gastrointestinal distress, liver damage and respiratory issues. Dogs are regularly sickened and killed by harmful blooms; this year, a puppy died within 20 minutes of playing in the Virgin River, which runs through Zion National Park and the city of Saint George. After a bloom has run its course, it poses another danger: The decomposing cyanobacteria cause oxygen levels in the water to plummet, resulting in fish kills.

Utah began to monitor water bodies for harmful algae blooms, or HABs, in 2016. It was one of the first states in the Western U.S. to do so, said Tina Laidlaw, HAB co-ordinator for EPA Region 8. Because monitoring began fairly recently, it’s hard to know whether the region’s toxic booms have been increasing in frequency or whether the data reflect improvements in reporting.

An algae bloom is classified as harmful based on the density of cyanobacteria cells and the concentration of toxins in the water. But scientists don’t fully understand why some blooms produce toxins in the first place, and not all cyanobacteria blooms are harmful. “Green doesn’t mean that it’s toxic,” said Ramesh Goel, professor of environmental engineering at the University of Utah.

In 2022, Goel received a $3 million grant from the National Science Foundation to study what makes certain species of cyanobacteria dangerous. Goel’s team is sampling HABs in Utah and beyond and comparing the genetic sequences of toxic and nontoxic species.

There is no easy way to stop harmful algae blooms. Prevention would likely require tighter regulations on fertilizer use, expensive upgrades to wastewater facilities to better filter out nitrogen and phosphorus, and improvements to rural septic systems to prevent leakage into watersheds. Even with such measures in place, accumulated nutrients in a water body’s sediment and surrounding watersheds can continue to fuel blooms for years afterward.

“I really cannot emphasize enough how important it is that we are aware of the nutrients we’re putting into our watersheds,” said Bonner.

Bonner is particularly concerned by the recent appearance of harmful algae blooms in high-elevation lakes, long thought to be protected by lower temperatures and less nutrient input. Panguitch Lake, at an elevation of more than 8,000 feet in southwestern Utah, was put under a toxic bloom warning for the first time this year.

“As we keep having a warming climate, and more and more human development interference,” said Bonner, “we’re going to see these blooms popping up in more and more places.”

Comments