One of the most important things that all Green and New Democratic Party MLAs agreed to in reaching their historic agreement to co-operate in governing together is their “foundational” support of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The declaration is absolutely unambiguous in stating the “urgent need” for governments to respect and promote the inherent rights of Indigenous peoples to their lands, territories and resources.

Enter the $8.8-billion Site C hydroelectric dam, a project that former premier Christy Clark vowed to push past the point of no return, but that remains years away from completion.

If ever there were a project that impacts First Nation lands and resources, and deserves to be a litmus test of the incoming government’s commitment to the declaration, Site C is it. The dam would flood more than 100 kilometres of the Peace River valley and its tributaries — resulting in irreversible losses for First Nations who have used and occupied those lands for thousands of years.

The West Moberly and Prophet River First Nations have spent years before the courts in a time-consuming battle to stop the project. But just last week, the Supreme Court of Canada rejected their final appeal. The nations argued that governments failed to properly consult them about the project and that the dam’s continued construction would irreparably harm their rights to hunt, fish and trap on their territories as covered by Treaty 8.

A task for the new B.C. government

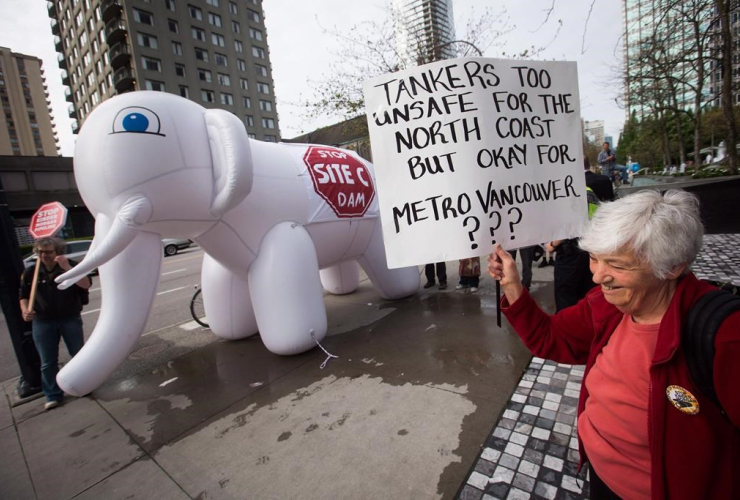

These realities are well known to all elected MLAs, many of whom also know that Saturday marks the 12th year in a row that hundreds of people will canoe down the Peace River to protest the dam and the devastating consequences it will have on local First Nations, farming families and others. Some of those same MLAs have joined the protest paddle in years past.

The NDP and Greens say that the project will be referred to the BC Utilities Commission for a review that focuses on the economic implications of the project. But will the incoming government also consider Site C’s obvious impacts on the First Nations of Treaty 8?

And will the government look more broadly at the pace of all industrial developments in the region and their impacts on Indigenous peoples? Because, as anyone who knows this corner of the province will tell you, it looks more and more like one giant industrial sacrifice zone.

Layer upon layer of environmentally devastating developments occur here. Nowhere else in B.C. do you see major hydroelectric, logging, mining and natural gas industry activities all happening simultaneously.

The “cumulative” impact of all this industrialization is jaw dropping. On the traditional lands of the Blueberry River First Nation (BRFN), there are so many natural gas wells, roads, seismic lines, pipelines, water pits, clear-cut logging blocks and other government-sanctioned industrial developments, that for three-quarters of the nation’s territory you are never further than 250 metres from the nearest industrial development. Local populations of moose, which BRFN members are supposed to enjoy treaty-protected rights to hunt, are in drastic decline.

Time to scrap a broken system

If there is any good news, it’s that the BRFN has said, 'enough is enough.' With each passing day, it inches closer to a date in court where it is seeking damages from the province for the “cumulative” degradation to its lands and waters from decades of government-sanctioned industrial developments. If successful, the civil suit will send an important signal that governments will be held to account for their consistent failure to respect First Nations’ rights.

The BRFN’s actions underscore the need to do things differently. We believe that one place to start is by granting First Nations sufficient powers to shape if, where, when and how resource developments of all stripes occur on their traditional lands. Co-management, if you will.

The time is long past due to scrap a broken system where First Nations are relegated to the subservient role of simply being told to respond in a timely way to one development application after another. This fundamental reform would mark a significant turning point in how the provincial government works with First Nations in the region, and would inch it closer to living up to its commitment to support the UN Declaration.

If this year’s “Paddle for the Peace” helps in some small way to set the stage for such reforms, the region and all its residents will be the better for it.

— Grand Chief Stewart Phillip is an Okanagan Indigenous leader and has been president of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs since 1998. Ben Parfitt is a resource policy analyst with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and recent author of Fracking, First Nations and Water: Respecting Indigenous rights and better protecting our shared resources.

This article confirms my

This article confirms my pleasure at being an Ontario resident who donates to West Coast indigenous resistance to environmental damage through donation sites such as Raven--or directly to tribes or tribal alliances. As a product of the settler invasion, and coming face to face with our hundreds of years of deep wreckage, I am grateful for indigenous wisdom and look for opportunities to help bring forward cases to the courts of law. Migwitch.

Comments