International watchdog slams B.C. for lack of "rigorous science" in allowing grizzly bear trophy hunt. Fourth in a series on trophy hunting of grizzly bears in B.C..

Allan Thornton, president of the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), spent six years working on a campaign to protect British Columbia's grizzly bears from habitat loss, excessive sport hunting, and the illegal trade of bear parts.

The EIA, a British organization that investigates international environmental crimes like the illegal trade of ivory and tiger parts, started looking into the management of grizzlies in B.C. in the late 1990s because it suspected the bears were being managed for destruction.

“The British Columbia wildlife department does not use rigorous science,” Thornton said of the provincial government's grizzly bear research.

The grizzly campaign attracted attention around the world, including that of the European Union (EU). The EU analyzed B.C.’s grizzly hunt and ruled it environmentally unsound. In 2004 they instituted an embargo, making it illegal to bring any part of a grizzly bear from B.C. into a European Union member country.

The ban was implemented with the condition that it would be repealed if the provincial government could provide the EU with scientific verification that the hunt was being managed sustainably, according to a B.C. government report. The provincial government contested the ban, which discourages Europeans from trophy hunting in B.C., but they were unable to provide the needed scientific evidence.

“Twenty-eight European countries are not allowing your commercially hunted trophies into their imports, why is that?" asked Thornton. "If it is such a good sustainable policy why can’t you show the science to be rigorous and accurate? Because the science, as far as we are concerned, is not rigorous or accurate."

Over a decade later, the EU embargo on B.C. grizzly bears is still in effect.

“I think the science the government uses to manage grizzly bear populations is poor, characterized by so-called 'expert opinion' in the near absence of on-the-ground data,” Chris Darimont, Hakai-Raincoast conservation biologist at the University of Victoria, told the Vancouver Observer.

Brown bears, of which grizzlies are the North American subspecies, were once found on four continents, making them one of the most widespread mammal populations in the world. Their original range included Europe, North Africa, northern and central Asia, the Middle East, and North America. Today, they are locally extinct or endangered across the map — except in Russia, Alaska, and B.C.

According to the provincial government's 2002 report on B.C. grizzly bears, in North America healthy grizzly bear populations once extended from northern Mexico to the Yukon, and from the West Coast to Hudson Bay.

As human populations began to expand, grizzly numbers steadily declined as their habitats became fragmented and their food sources threatened— and they were killed for recreation, or for getting too close to the people who were moving into their territory. Mexico's grizzlies are extinct and the last known Californian grizzly was shot dead in the 1920s.

British Columbia and Alaska are the last strongholds of the global grizzly bear population, though the exact numbers are contested because the bear's solitary and roaming nature makes them difficult and expensive to study. The B.C. government estimates there are 15,000 grizzly bears in the province today, but Darimont thinks there could be as few as 6,000.

For brown bears, the global trend is towards extinction. The Himalayan brown bear has dwindled to two per cent of its former range and there are an estimated 49 brown bears left in Italy. The Liberal government maintains the fate of B.C.’s grizzly bears will be different, but the government's scientific justifications for the hunt are harshly criticized by many local and international scientists.

Darimont, Kyle Artelle, and their colleagues at University of Victoria did an audit of the province’s grizzly bear harvest strategy. The audit, led by Artelle, was a peer-reviewed article in the journal PLOS ONE.

They calculated grizzly death rates using the government’s own figures. Their basic research question, Darimont explained from his University of Victoria office, was: “How did the government do? Did they keep grizzly bear mortality levels below their own thresholds?”

“And the answer is, 'Not very well,' based on their own criteria.”

“Grizzly bear harvest is based on the best available science," a Ministry of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations email said in response to questions about grizzly management. "The principles behind our decisions are: a reliable population estimate; estimates of sustainable human-caused mortality rates; and conservative mortality limits.”

Basically, the allowable mortality rate attempts to reflect how many grizzlies hunters can kill taking population levels, natural grizzly birth and death rates, and other human-caused mortalities (road kills, poaching, bear-human conflicts) into consideration.

Through the provincial Wildlife Act, the government sets limits on how many grizzly bears can be killed before population levels start to decline. But as Artelle and Darimont’s research illustrates, the province’s own records show they have historically allowed hunters to kill beyond those limits.

“Excess mortality may have occurred up to 70 per cent of the time,” said Darimont of the study’s findings.

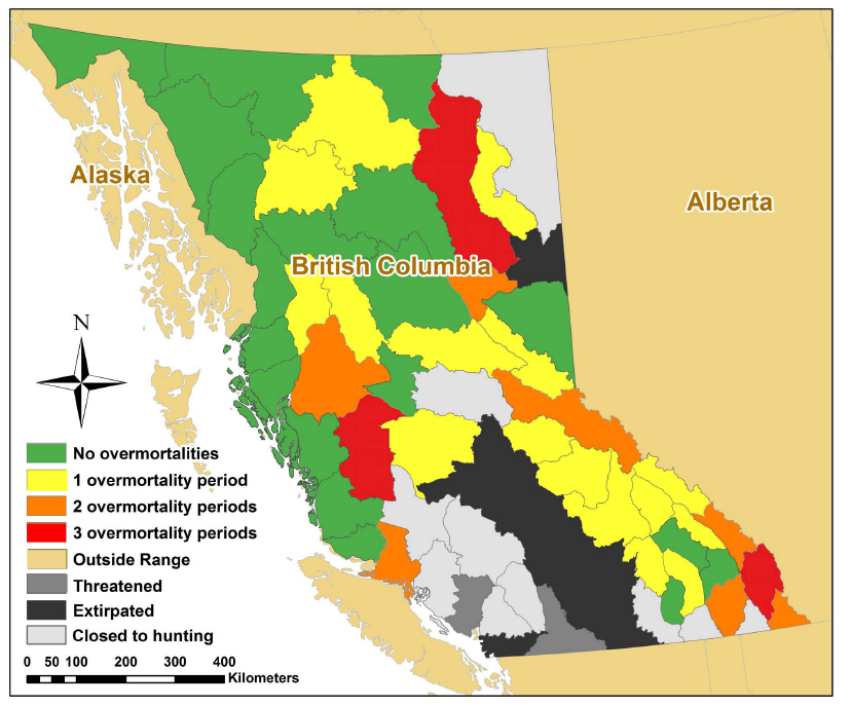

Turning to a map that illustrates how often the number of grizzly bears killed exceeds the government’s allowable harvest threshold, Darimont pointed to the black regions and said:

“We don't have bears here anymore in these light grey areas. Where they still occur, in at least half that space they screwed up at least once, and they’re not even catching themselves. They’re not even evaluating how they did.”

Number of allocation periods in which female or total overmortality occurred in B.C. Grizzly Bear Population Units. Image from the Artelle et al. report.

“I have seen the province lead resources away from the science so that people essentially don't know what the [population] levels are, particularly around grizzlies,” Nathan Cullen, MP for Skeena-Bulkley Valley, said.

“It’s a bit like a pipeline review, when doubt is cast on the impartiality of the government, then it cascades down on the whole industry.”

Paul Paquet, along with a panel of other Canadian scientists, was appointed to a grizzly bear scientific advisory committee by the provincial government in 1993. The panel was tasked with helping guide a redirection of grizzly bear conservation in B.C., to modernize grizzly management to adjust for contemporary threats to the animal’s wellbeing.

“What we found as an advisory group was that the province's interest in really using science and trying to do things in an improved way wasn't really there, to the degree that it should have been,” said Paquet.

“It is presented to the public as being rigorous and very serious in terms of management that is based on – in the terms they use – 'the best available science.' Practically, that isn’t what occurs.”

Comments