Statistics Canada has been offering a “quid pro quo” to cannabis retailers across the country: give us your sales data, and we won’t pester you with surveys.

Jim Tebrake, a director general at the federal statistical agency who has been examining how Canadians buy and consume cannabis ahead of legalization on Oct. 17, revealed the tactic as part of a panel discussion Thursday in Ottawa.

Canada is less than a week away from becoming the first G20 country to legalize cannabis nationwide for recreational purposes. Statscan has been making some unconventional moves to get its hands on data about cannabis use.

For example, it has been collecting sewage samples from different cities and sending them to McGill University to see how much THC, the active drug in cannabis, shows up.

Combined with the knowledge of how much water flows through a sewage system, as well as the local population count and the biology of how THC is metabolized, they can estimate consumption levels.

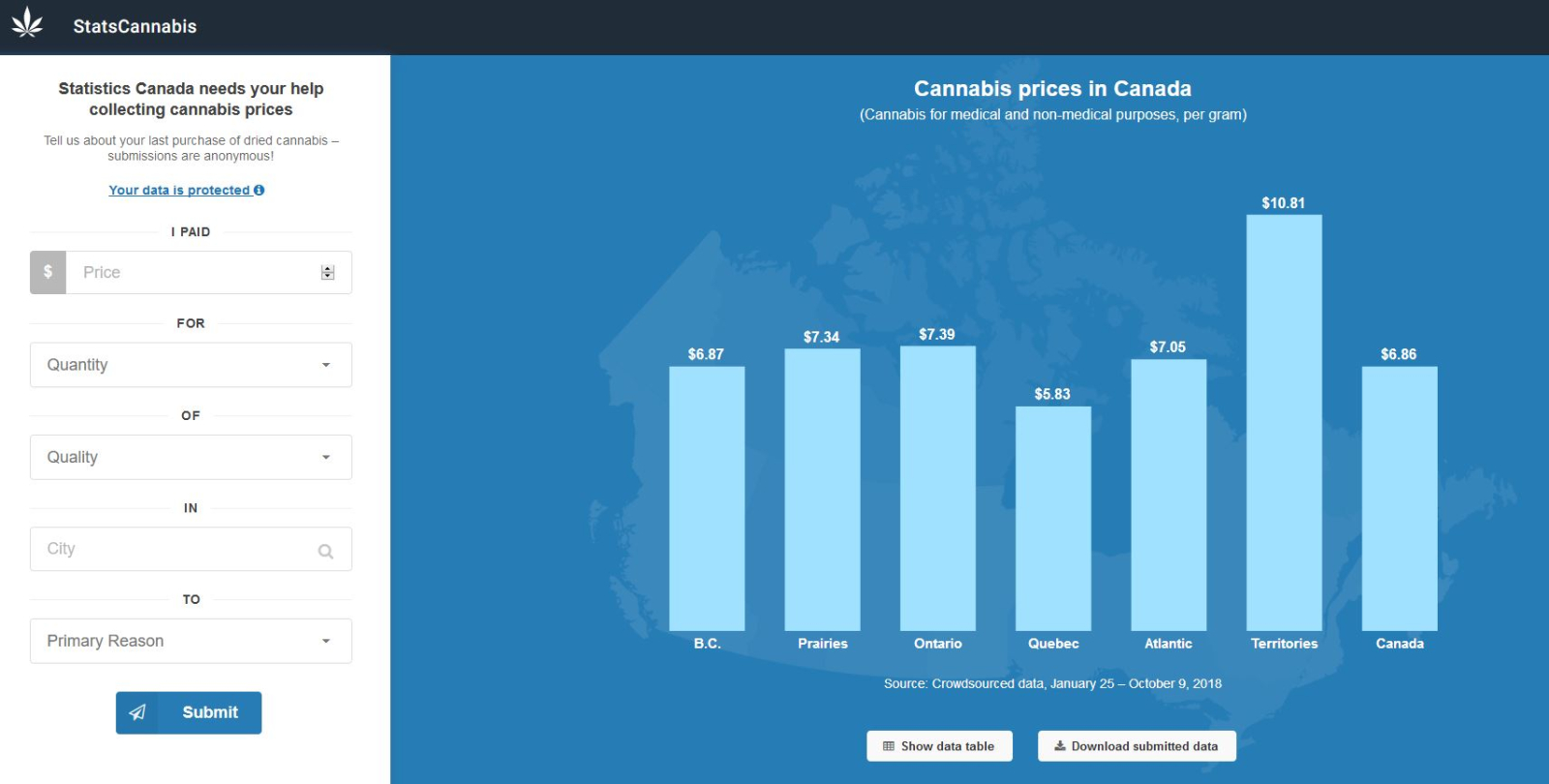

They also launched StatsCannabis, an online application that crowdsources data on how much Canadians paid for a gram of weed, how much they bought, where and for what purpose.

And it has been releasing the results of its National Cannabis Survey, which revealed today that about 4.6 million, or 15 per cent of Canadians 15 and older, reported using cannabis in the past three months.

On Thursday, Tebrake discussed how the agency wants to compare those two sources of data with information from federally-licenced producers, and from point-of-sale companies.

“If there’s a digital print of a transaction out there, our job is to try and get that digital print, or that regulatory form, rather than adding burden to respondents,” said Tebrake, who works in the agency’s macroeconomics accounts branch.

“We’re trying to work with a lot of these point-of-sale companies — working with the retailers — to implement their point-of-sale systems to get at that data. And the offer is: survey relief from Statistics Canada, but Statscan needs access to the point-of-sale data. So that’s kind of the quid pro quo.”

What illegal market will remain after legalization?

Tebrake said he began examining cannabis roughly when the Trudeau government introduced its legalization legislation in April 2017. The agency wants to be authoritative on things like the impact of cannabis on GDP, the price difference between the legal and illegal market, how many people have switched markets, and investment and employment in the industry, he said.

The National Cannabis Survey, conducted every three months, drills down on usage specifics. Today’s release showed consumption is more common and more frequent among younger men. It also showed more residents in Nova Scotia and British Columbia using cannabis than the rest of Canada, and that one in three users reported not paying, thanks to sharing.

StatsCannabis is getting upgraded to be more thorough, said Tebrake. He said he's seen a "strong correlation" between the number of responses and media coverage of cannabis. “We’re going to be relying on the media again in the next week as we revamp the crowdsourcing site to ask more questions,” he said.

The sewage samples will also continue, because it allows the agency to track the spread between legal and illegal consumption.

“The big question is, what’s the remaining illegal market, post-legalization?” said Tebrake. “If we’re going to get good supply numbers for the legal producers, one way to get at the remaining illegal market is to get good demand numbers and compare the legal supply to the legal and illegal demand.”

Statistics agency looking at modernization

This year, Statistics Canada is celebrating its centennial, or 100 years since the creation of its predecessor, the Dominion Bureau of Statistics. As a result, the agency is looking at how to modernize its operations.

Karen Mihorean, the director general of the agency’s education, labour, income and tourism branch — which produces items like the labour force survey — said the agency is hoping to publish data more quickly and with greater detail, and give greater access to users while still respecting privacy.

Many Canadians now have access to technology like call display that allows them to screen direct calls from statisticians more effectively, said Mihorean, so seeking out alternative data sources is increasingly important.

“I think long gone are the days of asking people questions over a telephone, or in their home spending maybe 45 minutes or an hour,” she said. “We still maintain good response rates and produce quality data, but we’ve worked really hard.”

One challenge facing the agency is that quite often Canadians’ data is being stored outside the country. For services that Canadians use like Uber or Airbnb that are foreign companies, there isn’t an entity in Canada that the agency can access to get information on their activity, said Tebrake.

“How far can the Statistics Act reach across the border?” he said. “We’re starting to see how far we can push.”

Daniela Ravindra, director general of the agency’s “economy-wide statistics” branch that produces items like the Consumer Price Index, said she’d like to see Statistics Canada data appearing more often at the top of people’s Google searches.

That means the agency has to become quicker in getting data into users’ hands, she said — including through possibly publishing information that’s “not necessarily in its final stages.”

An example she gave is data on geographic areas that doesn’t include all the areas where data is available.

She also said more users — not just statisticians, economists, and other experts — need to be able to relate to the agency’s data. Statistics Canada has been trying to boost its production of infographics, social media posts and other methods of delivering information.

Comments