In the days since British Columbia’s legislature enshrined a United Nations declaration on Indigenous rights into law, the move has been hailed as an historic victory.

B.C.’s bill, passed Nov. 28, makes it the first Canadian jurisdiction to align its laws with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) — a landmark international document which protects the Indigenous right to self-government, and a large number of fundamental human rights including safety from genocide and assimilation.

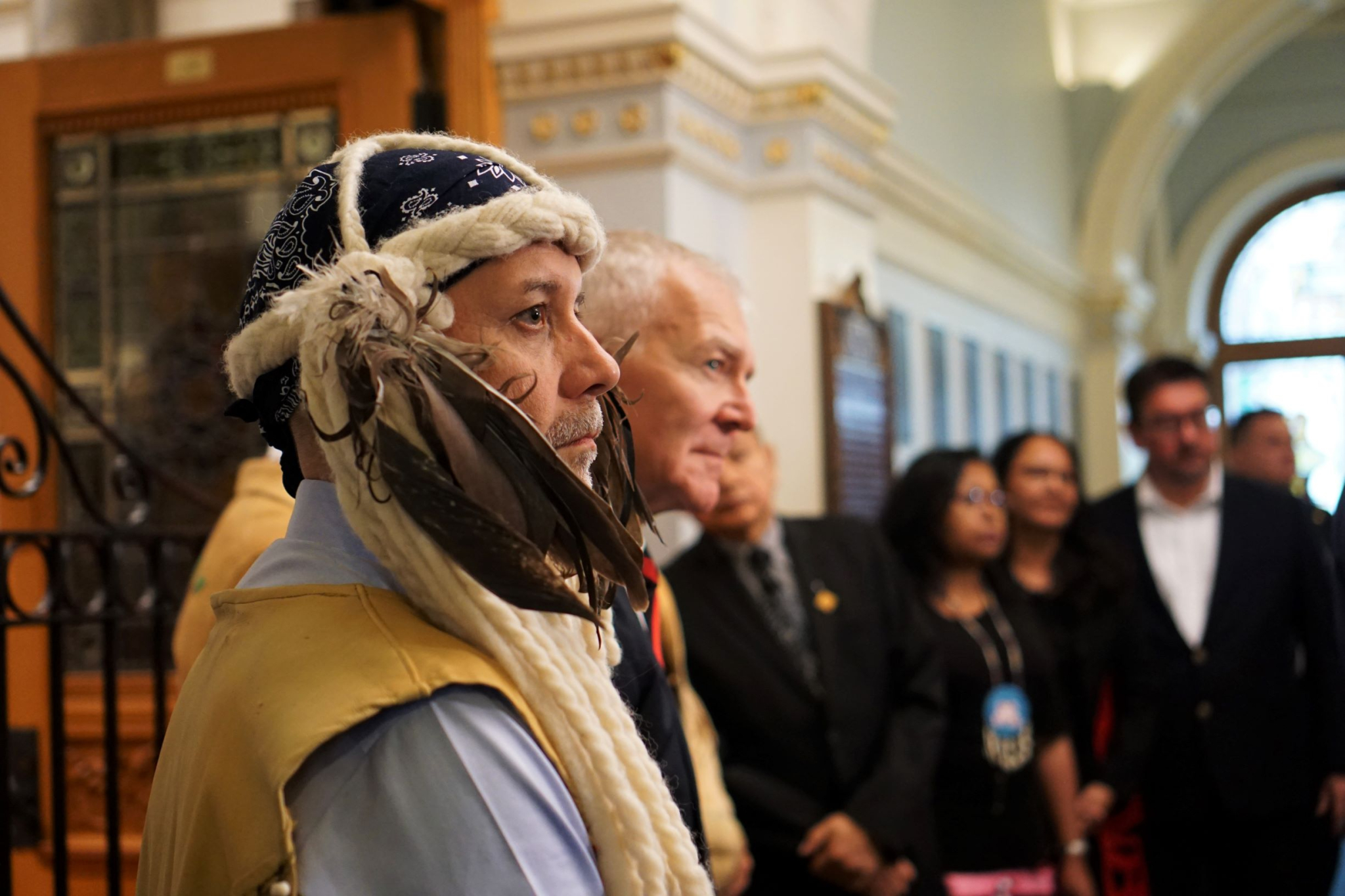

When the bill was first introduced on Oct. 24, Lekwungen dancers opened the floor, Indigenous leaders welcomed a new era of change and the first reading passed unanimously.

While it was a jubilant celebration, Indigenous leaders also slipped in a few jokes about how long it has taken for any government in Canada to reach this step — nearly 13 years.

“Did you hear that?” asked Cheryl Casimer, a member of the First Nations Leadership Council, after the bill was introduced. She left the house waiting in silence for a few seconds.

“The sky did not fall,” she quipped.

Canada’s path toward UNDRIP has been long and reluctantly taken. It was one of just four states to vote against UNDRIP when it was passed by the UN General Assembly in 2007, citing concerns about a measure that requires Indigenous consent for resource-development projects (another 144 countries voted in favour).

But nearly 9,000 kilometres to the south, Bolivia has been a global leader in Indigenous rights for years and, until recently, had the only Indigenous leader in the United Nations.

Bolivia was the first country to implement UNDRIP. Evo Morales, Bolivia’s first Indigenous president, took office in 2006 and enacted a flurry of changes that made life better for Bolivia’s Indigenous population. While Canada stalled, Bolivia has long been held up as a beacon for how successful a country with strong Indigenous rights can be.

But Indigenous rights have been thrown into crisis since the newly re-elected Indigenous president was exiled by a conservative faction following the election.

“That means that it’s even more important that we follow through on these positive pushes (in Canada),” said Sheryl Lightfoot, an Anishinaabe associate professor at the University of British Columbia and Canada Research Chair in global Indigenous rights and politics. While many countries have swung to the right, she says, Canada and New Zealand are now part of a “lonely club” of countries making progressive changes for the global Indigenous rights movement.

Canada has trailed behind Bolivia, not issuing a statement in support of UNDRIP until 2010.

It took another six years to drop its objector status and adopt the declaration. And soon afterward, the federal government approved the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project against the objections of several local First Nations.

Though the 2016 reversal came with a pledge to make UNDRIP into federal law, that hasn’t yet happened. (The Liberal government renewed that promise during this year’s election campaign.) Meanwhile, perpetual and vast inequality has led special rapporteurs from the UN to tell Canada more than once that it’s failing Indigenous Peoples.

Now that B.C. has taken the step to implement UNDRIP, Indigenous leaders know there is still a long path before the bill may begin to shift systemic issues that perpetuate inequality.

“There is no understanding of how long it’s going to take to address unfairness in the criminal-justice system, unfairness in the child-welfare system, unfairness in economic development,” said Green party MLA Adam Olsen, or SȾHENEP, from Tsartlip First Nation, in an interview with National Observer after the first reading. “What we do know is the provincial government is coming to the table in goodwill.”

‘It's supposed to be much more revolutionary’

Like Canada's Constitution, UNDRIP guarantees certain human rights to Indigenous people. But, if fully implemented, UNDRIP could empower Indigenous Peoples in ways the Constitution can't by recognizing ongoing systemic injustice and the Indigenous right to self-government.

UNDRIP also enshrines the collectives rights of Indigenous Peoples. While the Constitution asserts the rights of the individual to be equal before the law, UNDRIP asserts Indigenous Peoples "possess collective rights which are indispensable for their existence, well-being and integral development as peoples" to live in freedom as distinct societies.

These provisions are also what have made UNDRIP controversial in Canada. Among the declaration’s 46 articles — approved in 2007 after two decades of international negotiation — are requirements for restitution, Indigenous consent on resource-development projects and recognition for Indigenous legal systems.

In 2016, former Liberal justice minister Jody Wilson-Raybould said legally implementing UNDRIP was “unworkable” for Canada because adopting it as law would be a “political distraction to undertaking the hard work actually required to implement it.”

Federal NDP MP Romeo Saganash introduced an independent bill to legislate UNDRIP. However, it died in the Senate this year after Conservative senators opposed it over fears that Indigenous consent requirements amounted to a veto on oil and gas development.

The problem is that while there are 46 articles in UNDRIP, the Canadian government hasn’t been looking at all of its elements “holistically,” said Roberta Rice, an associate professor at the University of Calgary who focuses on Indigenous politics in Latin America.

“The idea seems like the Canadian government is picking and choosing what it's going to implement, which is the problem,” Rice said. “It's supposed to be much more revolutionary.”

Bolivia, meanwhile, took a swift, far-reaching approach.

When Morales formed government, he abolished the department for Indigenous rights, choosing instead to make them a priority for his entire government. He created a ministry of decolonization, which includes a “depatriarchalization” unit devoted to dismantling colonialism and patriarchy within government.

The Bolivian constitution was rewritten in 2009 to incorporate UNDRIP and to allow Indigenous territories to govern themselves. The constitution officially changed Bolivia to a “plurinational state,” recognizing the country’s many Indigenous Peoples rather than only the nation-state. It also identified three dozen official Indigenous languages alongside Spanish — depending on where you are in the country, that region’s dominant Indigenous language appears on official signage.

And, in 2010, Bolivia was one of the first countries to recognize the rights of waters and lands, not just humans, with its Rights of Mother Earth Law.

“They were the only state at the time, in the 2000s, that had significant forward movement in Indigenous rights implementation within the legal political framework,” Lightfoot said, “and, of course, the only UN member state with the Indigenous leadership. So Bolivia had a heavy set of expectations on it during that time to lead in many ways on the global level.”

And while Bolivia took bold steps to enshrine Indigenous rights, the country prospered.

Bolivia’s socio-economic progress has been praised by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Between 2004 and 2017, Bolivia’s annual real GDP growth was 4.8 per cent on average, according to the IMF. Meanwhile, the percentage of the country’s residents living in poverty — an issue that primarily affects Indigenous people, according to Unicef — dropped from 34 per cent to 17 over the same time period.

This process hasn’t been perfect. The Morales government did not include UNDRIP’s key term, “free, prior and informed consent” when it incorporated the document into the constitution. Instead, the constitution gives Indigenous Peoples the right to consultation and leaves the power and final decision-making in the hands of the state.

Morales shifted resource extraction under the control of the federal government, a move that’s at odds with UNDRIP’s requirements that Indigenous Peoples be involved in the process. He also lost Indigenous support over attempts to build a controversial highway through Bolivia’s southern Amazon, against the wishes of local Indigenous communities.

“Morales’ whole model was to try and use extractive industry in a good way and reinvest into poverty-alleviation programs that will target and help the Indigenous poor, which he has been doing,” Rice said. “But of course, you create conflict when you build highways through indigenous territories... implementing in practice has been the big challenge.”

An extraction-based economy is directly “at odds with Indigenous autonomy to land,” Rice said, meaning Indigenous Peoples in Canada have faced similar difficulties having their rights recognized by the Canadian government.

“The whole idea of respecting the rights of nature and Indigenous ways of knowing and being, but in an extractive economy that needs resources that are under the feet of Indigenous people — it's all a big contradiction,” she said.

‘Emotionally difficult’

Progress is never linear, and Indigenous rights in Bolivia now appear endangered as the country joins much of the rest of the world in a swing toward the political right.

Official results showed Morales won an Oct. 20 election, but the Organization of American States (OAS) challenged the results, claiming there had been serious irregularities with the vote — a statement that critics have questioned in the weeks since the election, pointing to a lack of evidence. Nevertheless, the OAS allegations helped spark anti-Morales protests across the country, and pro-Morales protests in response.

Morales resigned on Nov. 10 and fled to Mexico amid pressure from the military. In seeking a fourth presidential term, he didn't have anything approaching uniform support, even within his core coalition, but nevertheless, many observers see his exile as arising from illegitimate ouster of a democratically elected government.

More than 30 people have died in the protests, most of them after the military was deployed against Morales supporters, according to Reuters.

Paulo Fernando Tudela, a medical student going to school in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, said his country’s current tensions are “intricate.” Tudela is mestizo, meaning he has mixed Indigenous and European ancestry.

“On one side, Evo Morales has performed miracles for our economy and the country has grown impressively since he took over,” Tudela wrote in an interview conducted over Facebook from his hometown of Rurrenabaque, a small town in northern Bolivia.

“On the other side, we argue that it is unhealthy for somebody to stay in power for too long.”

Tudela said he’s concerned the far-right government that seized power could undo years of progressive policies under Morales: “We improved so much as a country and it’ll be a shame to see it go to waste.”

Bolivia’s interim leader, an opposition senator named Jeanine Áñez Chávez, initially appointed zero Indigenous cabinet members (she later added one amid public outcry). She’s also come under fire for past tweets where she mocked Indigenous culture and called Morales a “poor Indian.”

Acabo de promulgar el D.S.4100 con el que se autoriza otorgar asistencia humanitaria e indemnización a los familiares de los fallecidos y heridos en los hechos de violencia surgidos en el país después del fraude del 20 de octubre. pic.twitter.com/Ac3cH2Ptxq

— Jeanine Añez Chávez (@JeanineAnez) December 5, 2019

“We have watched Bolivia make important inroads in Indigenous rights and Indigenous recognition since the Evo Morales government came into power,” Lightfoot said.

“So to watch that change so suddenly, and the swing to the right that seems to be happening, is devastating. Because now, we've lost our one Indigenous government that we had as a member-state. But then also just to watch the happenings on the ground is emotionally difficult.”

The fact that Bolivia is in turmoil makes Canada’s role in recognizing Indigenous rights even more important on the international stage, she said.

“In Canada at the moment, we've got a unique environment, globally. We are actually pushing forward on the Indigenous rights agenda,” Lightfoot said.

Rice predicts Morales’ legacy will outlast the current crisis.

“You can't imagine, even without Morales in power, Bolivia would ever go back to not talking about Indigenous rights. It's so part of the norm now that all parties, even the most conservative parties, have to have a stance on Indigenous rights. (It’s) the same here in Canada,” she said.

“That is a shift.”

![Evo Morales, who resigned as president of Bolivia and sought asylum in Mexico amid political turmoil earlier this month, repeatedly proclaimed himself a guardian of “Pachamama,” also known as Mother Earth. Photo by Joel Alvarez (Joels86) [CC BY 3.0]](https://www.nationalobserver.com/sites/nationalobserver.com/files/styles/nat_teaser/public/img/2019/12/03/1024px-bolivia_evo-morales_government_joel_alvarez.jpg?itok=6qJH-BKp)

Comments