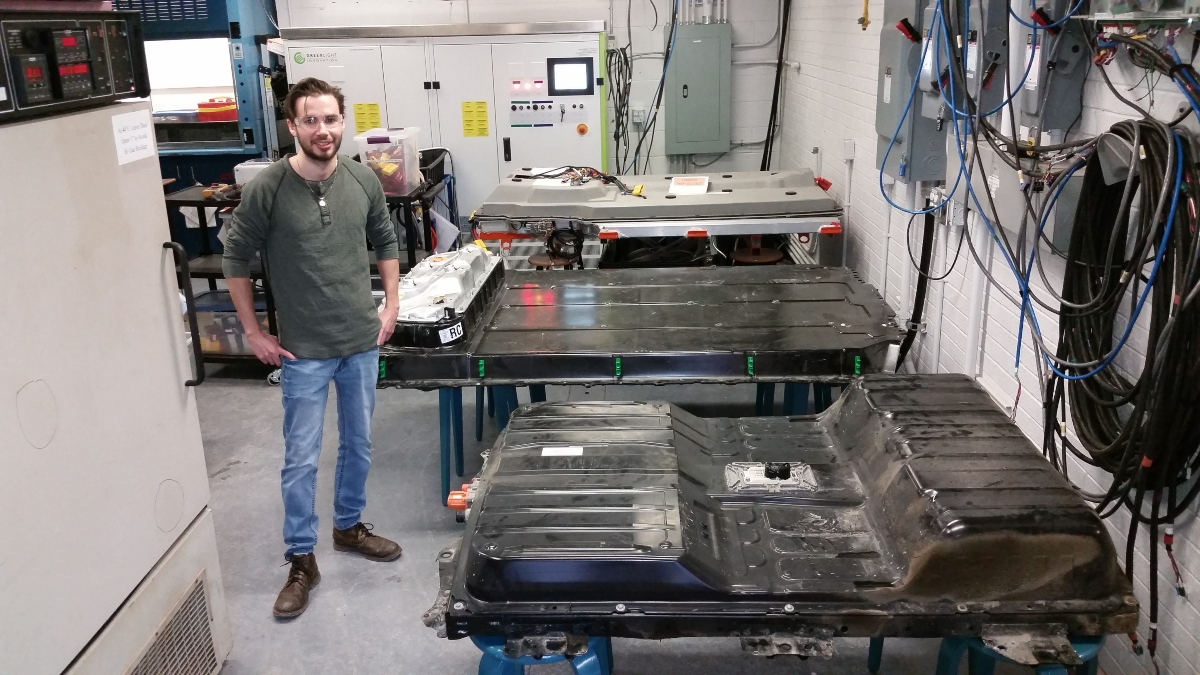

Chris White’s PhD thesis aims to help us reduce and reuse electric vehicle batteries. This 31-year-old is also the chair of the Nova Scotia Environmental Network, which is strengthening Nova Scotia’s environmental groups by connecting organizations with government decision-makers and volunteers and sharing research and ideas for change.

This piece is part of a series of profiles highlighting young people across the country who are addressing the climate crisis. These extraordinary humans give me hope. I write these stories to pay it forward.

Tell us about your research.

All electric vehicles use lithium-ion batteries, which, over time, lose a percentage of their ability to store energy. When the vehicles reach the end of life, the batteries typically still have plenty of juice left and should be reused before they are scrapped and recycled. But consumers need fresh batteries in their new EV purchases to reduce range anxiety. In the near future, there will be millions of used EV batteries that can still provide valuable energy storage but need to be repurposed.

Companies around the world have recently begun collecting used EV batteries and repurposing them for electricity grid applications. This is a great solution because electricity grids need affordable energy storage to rely more on wind and solar energy.

Repurposed batteries are more affordable and sustainable than new ones, but they are challenging to work with because there are so many different EV battery designs. I am building an algorithm to make it easier to connect different repurposed EV batteries to work together.

What drew you to leadership in the Nova Scotia Environmental Network (NSEN)?

In 2017, I participated in the Canada C3 Expedition, sailing on a retired Coast Guard icebreaker in Nunavut. I was deeply affected by the many stories I heard from Inuit and other Indigenous people about the history of colonialism and its ongoing impacts. In KugIuktuk, we learned the community overcame a devastating youth suicide epidemic by coming together to support and connect with one another. I had never made much effort to get involved in my own community, but I felt inspired to start. I started volunteering with a few groups that supported environmental and Indigenous causes. NSEN was one of those.

NSEN used to be a vibrant force, but in 2011, the federal government stopped funding environmental networks. When I joined in 2017, there were just a handful of volunteers left, and I offered to help. We modernized NSEN and rebuilt its capacity so we could win grants and keep growing. Now we have three full-time staff who are building new connections and collaborations across the environmental community.

Often these organizations are quite small, so one additional volunteer can make a big difference. Through our volunteer hub, Nova Scotians of all ages and abilities can make the kind of contribution that so many are anxious to make. It is like a large tight-knit family with room for us all.

What got you interested in EV batteries?

I didn’t have a plan, but followed opportunities as they arose. I made an early undergrad switch from science to engineering thinking it would be cool to be an aeronautical engineer. After some experience working with lithium-ion batteries, wind turbines and solar panels, my interests shifted to renewable energy. In my final semester, my professor invited me to do a master’s program on battery research.

During my master's, I got to do an internship at Tesla Motors in California, and I thought I might start a career there. But our Dalhousie team had some great battery research ideas of our own, so I decided to stick with it. We have since earned two patents for our work and I got the invitation to do this PhD. I hadn’t planned to go back to school, but I saw an opportunity to have a real impact.

What makes your work hard?

Research is hard because you are doing something no one has done before. You are largely on your own. Finding the balance between work, volunteering, family and self-care is really challenging. Finding sustainable funding is very difficult for NSEN. It is not reasonable to expect these vitally important organizations to continue to run on volunteer time.

What gives you hope?

Progress is real. If you had told me three years ago that NSEN would have three full-time staff, I would not have believed you. Governments see grassroots environmental initiatives as in society’s interest and increasingly understand it is unrealistic for volunteers to carry the entire load.

What advice would you give other young people?

If you aren’t sure what you want to do with your future, find something you can do a good job on and take the opportunities that come up. The path to your future might take a winding road you could never predict. If you have time to volunteer that can be a great in-road.

What would you like to say to older readers?

Get involved, even if you have never volunteered before. Young people cannot do this alone. I had no volunteer experience before I joined NSEN, and now it is a huge part of my life that I really cherish. If you aren’t able to offer your time, donations go a long way for small environmental non-profits.

Comments