This story was originally published by The Guardian and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

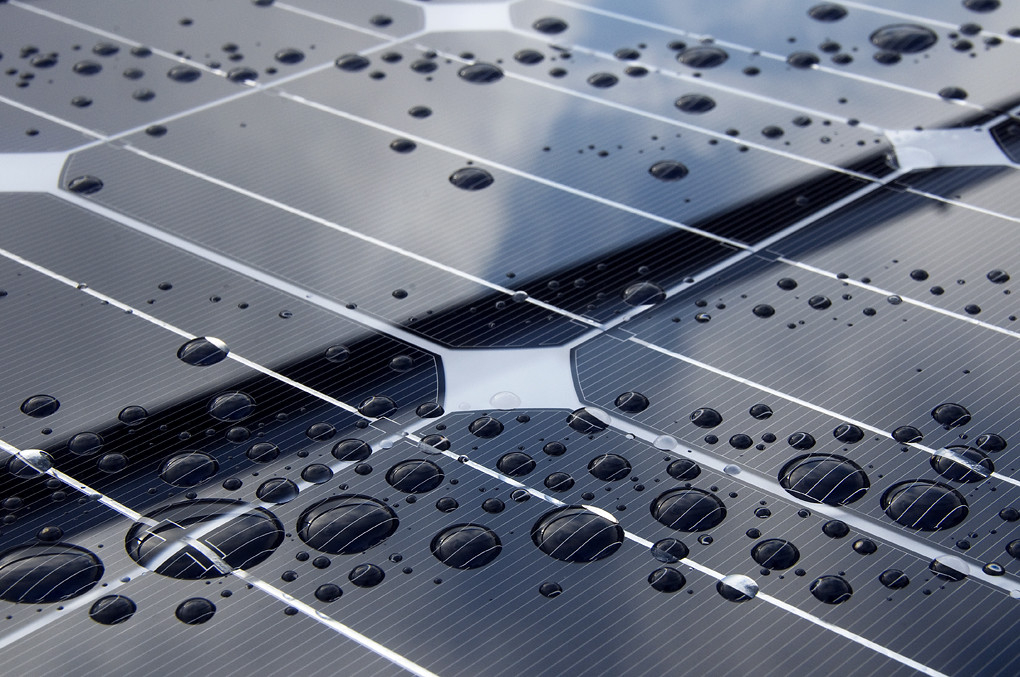

Researchers have created a solar-powered device that produces hydrogen fuel directly from moisture in the air.

According to its inventors, the prototype produces hydrogen with greater than 99 per cent purity and can work in air that is as dry as four per cent relative humidity. The device would allow hydrogen to be produced without carbon emissions even in regions where water on land is scarce, they say.

Hydrogen is a zero-carbon fuel that yields only water as a byproduct when combusted. However, pure hydrogen is not abundant in nature and producing it requires energy input. Large-scale production commonly involves fossil fuels that generate carbon emissions.

The study’s lead author and a senior lecturer in chemical engineering at the University of Melbourne, Dr. Gang Kevin Li, said the hydrogen-producing device could be powered by solar or wind energy.

A prototype produced hydrogen for more than 12 consecutive days in a monitored trial. “[For] one of them, we left it to run by itself for eight months,” Li said.

The device is comprised of spongy material with a hygroscopic liquid — fluid that absorbs moisture from the air, similar in function to silica gel sachets. The absorbed water molecules are then split at electrodes into hydrogen and oxygen gasses, a process known as electrolysis.

“Hydrogen is the ultimate clean energy … as long as you have renewable sources of energy to electrolyze the water,” Li said.

The device is estimated to produce up to 93 litres of hydrogen a square metre an hour. “If you have 10 square metres of this unit, you can power a whole house … to replace your consumption of natural gas at home for cooking and heating,” Li said.

The prototypes are still only small in size, and the team has plans to create one-square-metre and 10-square-metre units in the coming year.

The researchers envisage the device could be a useful tool in regions where liquid water is not readily available for producing hydrogen. “Large parts of the world have water scarcity problems,” Li said. “When you have lots of renewable energy — wind or solar — you [often] don’t have much fresh water for this type of hydrogen production.”

Dr. Kim Beasy of Swinburne University’s Victorian Hydrogen Hub, who was not involved in the research, said hydrogen fuel, while important, was not a silver bullet for reaching net-zero. “We’re coming to understand that hydrogen is going to be one piece of the puzzle,” she said.

“It’s going to provide us with direction out of some pretty hard-to-mitigate industries, such as transport. We have no alternative to diesel at the moment … hydrogen is a really good option.”

The required economies of scale were “probably not going to be reached with clean hydrogen straight away,” Beasy said, citing the expensive price of conventional hydrogen electrolyzers. “What we really need is more government support and subsidies in bringing down the cost of getting this technology on the ground.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

I read this article when it

I read this article when it came out in The Guardian and was, then, singularly unimpressed by yet another article concerning energy which doesn't cover the necessary bases.

Please, can someone reputable offer a short masterclass for an audience of journalists on what important aspects must be considered and included when reporting on energy?

In this article, for example, I don't much care about the "purity" of the produced H2. I am, however, very interested in the amount of energy and materials that go into the process as it presently exists.

There is so much "aspirational" (optimist's view) yet "entirely useless" (realist's view) reportage regarding energy that, in my opinion, only serves to obfuscate and delay. Fusion energy is the poster child for this phenomenon.

Is it too much to ask of journalists and their employers that they arm themselves wuth sufficient knowledge before attempting to report on the topic?

Yes, yes it is. You may not

Yes, yes it is. You may not have noticed that all the money is going out of journalism, and something that leaves earlier is scientific expertise, since if they have a science or engineering degree in addition to J-school, they can probably make more money elsewhere.

What we're getting are the press release, dressed up; that's all the journalist has to work with, since they don't have time for calling up the source and asking questions, and it's unlikely they'd spot which questions to ask. The crucial one being, "how many kilowatt-hours of energy does this thing take to make a kilogram of hydrogen"?

If it's more than the just-developed electrolyser from Hysata (lowers cost from 52 kWh to 41), then the only new win here is the ability to make hydrogen far from water. Since water is pretty common, it has limited application.

Comments