The principal of McGill University is defending the institution's commitment to reducing carbon emissions after a professor resigned over its refusal to divest from the fossil fuel industry.

Suzanne Fortier said the institution's plan to reduce the overall carbon footprint of its endowment will ultimately be more effective than the "symbolic gesture" of pulling out of oil and gas stocks.

"We're working with a very concrete plan in diminishing our carbon emissions and we're looking at every single one of our investments to see where we can reach a lower carbon emission level in our portfolio and making sure we have targets and timelines we can meet," she said in a phone interview.

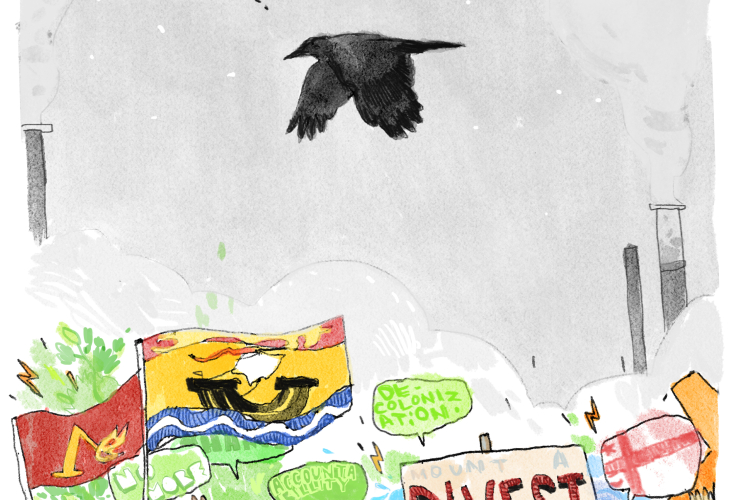

The McGill board of governors decided against divestment on Dec. 5, against the wishes of the McGill University Senate and several student groups. The move prompted Gregory Mikkelson, a philosophy professor who specializes in environmental ethics, to resign.

In an interview, Mikkelson said the board's third refusal in seven years to divest is not only morally questionable, but also undercuts the work of university academics and researchers who have long warned of the dangers of climate change.

"The first two times, in 2013 and 2016, they were already defying the strong basis for divestment in natural science, social science and the humanities — in other words the kinds of research universities do," he said in a phone interview.

"So they were kind of undercutting academic integrity at that point, and not to mention the moral integrity of not investing in industries that are wrecking the planet."

Mikkelson said the institution's decision is particularly "egregious" given that the Senate as well as "every faculty, student and staff organization that has considered the matter" has voted in favour of divestment.

Fortier, meanwhile, said that fossil fuels make up only about two per cent of the university's portfolio, or about $32 million, and that a move to pull out would be mostly symbolic.

However, she also acknowledged that a decision to divest could be financially tricky since it would involve removing all investments from any portfolio that didn't explicitly ban fossil fuel investments, even if they didn't currently have any.

She said that reducing emissions is a complex problem that will require a complete re-evaluation of how people move, feed themselves and buy goods.

"We're trying to go to concrete solutions," she said. "Symbolic gestures, we'll let others do that."

Several other Canadian schools including the University of British Columbia, Concordia University and Universite Laval have recently decided to stop investing in the fossil fuel industry.

Fortier's position is a disappointment to Audrey Nelles, an organizer with Divest McGill. The first-year student said she supports the university's position to lower the carbon footprint of its endowment, but stressed that this must be paired with divestment.

"They haven't announced their targets yet, but we know whatever they are going to do is not going to be full divestment, and it lacks the power that divestment has, because divestment sends a signal to policy-makers that we don't support this industry that has been complicit in the climate crisis," she said in a phone interview.

Nelles said the group has received hundreds of signatures of support from staff, students and donors calling on the university to divest. She said in the coming months the group plans to ramp up its pressure tactics, which in the past have included occupying the principal's office and camping out outside administration buildings.

"We're going to amplify this, we're going to escalate, we're not going to take no for an answer," she said.

As for Mikkelson, he believes his resignation has already served a purpose in raising awareness for the cause — judging by the media attention he's been getting.

"To use a cliche, my phone's been ringing off the hook," he said.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Jan. 20, 2020

-- With files from Giuseppe Valiante and Sidhartha Banerjee

Disgraceful that any academic

Disgraceful that any academic institution would not proceed with complete divestment from all companies in the fossil fuel industry.

Fossil fuel are bad for the planet, bad for all living species and very poor investment strategy as returns fossil fuel companies have had very poor capital gains in the last ten years and dividends are funded by new debt.

A losing investment on all fronts.

Peter

They won't divest because it

They won't divest because it is technically difficult? Probably the lamest excuse of all time. Follow the money, and you will learn why they did not divest. There is more to this story. Check the personal commitments of the members of the Board.

Dozens of universities have

Dozens of universities have divested in the UK. What's so difficult about this for Canadian institutions? Conflict of interest amongst the decision-makers perhaps? Time to bring in new Board members, it seems, those with a conscience. In the current era of absolutely corrupt and self-interested politicians in high places, it is meaningful to take a stand against corruption; certainly not a "token gesture". Likewise, when our children's lives and hopes are at risk due to the continual procrastination to move to non-fossil fuel energy, even when the science is staring us in the face, we need all the "token gestures" of declaring and demonstrating this to be unethical and harmful, that we can get. Actions have meaning. Mealy-mouthed words about "studying the situation" do not.

By the way, kudos and thanks

By the way, kudos and thanks to Professor Mikkelson. He is the type of professor (ethical and articulate) that I would like my children to learn from at uni. Hope he finds himself in a better institution shortly. Or preferably, back at McGill, having spurred them to ethical action, and with a promotion.

Comments