With the recent heat waves in Canada and across the world, the devastating and increasingly extreme effects of climate change on natural, social and economic well-being continue to become more pronounced, raising broad concern and growing awareness for Canadians.

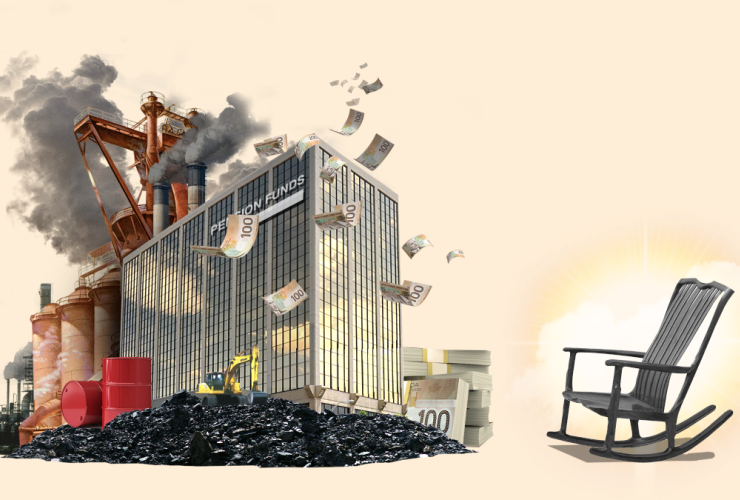

Canadians are directly connected to the drivers and solutions for climate change as consumers and voters and as savers, investors and pension holders. As fiduciaries, it is the responsibility of Canadian pension plans to act in the interest of their beneficiaries and it is increasingly clear that managing the risks presented by climate change falls within that responsibility.

Yet, many Canadians do not know how their pension plans are managing climate change. Smart Prosperity Institute’s latest analysis, supported by the Global Risk Institute, helps shed light on this critical issue, including what pension funds are doing to address climate risks and what needs to be done to build greater climate resilience.

Climate change presents different types of risks to pension funds. These include the risks associated with the physical impacts of climate change, as well as those associated with the transition to a low-carbon economy, which brings both potential disruption and opportunity.

At the same time, significant investments are needed in areas of climate solutions and clean growth, such as renewable/non-emitting electricity, smart grids, carbon capture and storage, low-carbon transportation technologies and others. Addressing climate risks could see pension funds using their supersized strength to help direct finance to these much-needed climate solutions.

In recognition of climate risks, eight of Canada’s largest pension funds have voluntarily committed to achieve net-zero emissions by mid-century or sooner. To act on these commitments, they have begun to develop plans to reduce their operational and portfolio greenhouse gas emissions. Some have also committed to bolster investments in climate solutions.

While this is encouraging, the implementation of these plans must include meaningful shorter-term action. The problem is that there are currently no binding requirements to track implementation of these voluntary commitments, nor any standardized climate-related disclosure to help beneficiaries follow the progress.

Our new analysis points to five ways pension plans can more effectively build climate resilience and trust.

First, pension funds, both large and eventually smaller ones, need to commit to net-zero emissions across their value chains by 2050 or sooner, and develop robust climate plans. This will match the pace of change committed to by Canada and many other global governments to achieve net-zero emissions, and would therefore ensure plans are transitioning at a speed that matches the worldwide low-carbon shift.

Second, pension funds need to invest in areas and companies that are themselves reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Since pension funds do not have direct control over most of their emissions profile, they need to actively engage with or divest away from underlying carbon-intensive portfolio assets, which means helping them develop effective net-zero transition plans of their own. Having a low-carbon transition plan could become a pre-condition for investment.

Third, both pension funds and their portfolio companies need to demonstrate their climate plans are credible. One way to do this is having these plans verified by third-party global initiatives like the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero and the Science Based Targets initiative.

Fourth, pension funds need to transparently report on climate solution investments, particularly if their voluntary climate targets include these types of commitments. Currently, funds have different methodologies to define “green” and “transition” investments, which make tracking progress challenging. In the absence of a Canadian-specific taxonomy, they should provide clear details on how they are classifying these investments, including sharing disaggregated data on which assets have been included in any related claims.

Finally, pension funds need to have better climate-related disclosures from their portfolio companies in order to improve their own disclosures. However, much of the information is either not available, difficult to obtain, or available only through data that is incomplete, inconsistent, and incomparable. While pension funds have asked for better disclosures from portfolio companies in line with global reporting standards such as the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, governments and other stakeholders have a crucial role to play in ensuring completeness and comparability of data provided.

Notably, the work of the Sustainable Finance Action Council will be important for Canadian pension funds to deliver on their commitments. The council has been tasked to provide guidance and advice on mandatory climate-related financial disclosures across broad spectrums of the economy, climate data needs and existing gaps, as well as green and transition taxonomies.

Net-zero targets, taken together with transparency commitments and alignment with global credibility standards, will ensure that pension fund administrators are effectively guarding against climate risk. Canadians are more aware than ever of the effects of climate change and look to their pension funds to strive for prosperity and well-being for generations to come.

Katherine Monahan has over 15 years of experience working in climate change policy development and analysis for the public and private sectors. Her expertise spans regulatory analysis, market-based approaches, energy policy and the nature-climate nexus.

Anik Islam is a research associate at Smart Prosperity Institute and works on sustainable finance, green industrial strategy and green fiscal policy development.

Probably pension funds should

Probably pension funds should be divesting themselves of Canadian carbon fuel assets at a rate faster than the market decline, since most of Canadian oil is of an ecologically undesirable grade, such that Canadian petroleum assets will predictably find no purchaser available long before 2050. Ditto companies that are exposed to the point they'd be left with both stranded assets and perhaps also a responsibility to remediate.

Comments