In our culture, there are two subjects where we tend to carefully guard our personal privacy: sex and money. Spoiler alert: Don’t get too excited — I’m here to talk about my finances. As strong as the taboo is against sharing details about our financial lives, what’s even stronger is my discomfort knowing some of my investments are not aligned with my values.

You may be wondering: How does a reasonably well-educated, former lawyer end up in this compromised situation on the day of RBC’s annual general meeting?

I didn’t learn about financial literacy in school, nor was it really taught in my family. Although my dad was passionate about investing, our family winced as his holdings suffered some painful losses. Investing in the market, dad-style, looked like informed gambling, and I couldn’t imagine going anywhere near that world of uncertainty and risk.

Around 10 years ago, I found myself needing to grow through a learning curve of financial self-sufficiency. When I suddenly needed to safeguard my personal assets, investing in the stock market started to look like a reasonable possibility.

Today, I’m definitely diversified, but not keen to support problematic industries. So, what have I learned that I think is noteworthy?

1. Identify your values and set limitations on what types of investments are acceptable.

Even 10 to 12 years ago, I was asking folks about green investing in Canada. Back then, my friends who were leading edge financial progressives told me there really weren’t any satisfactory green funds. Some had started to emerge, but what made them “green” was the absence of tobacco or toxins. Somehow, I couldn’t get excited about investing in things like robocalls and telemarketing.

The past few years, as consumer consciousness grows more aligned with climate concerns, there are increasing opportunities to make values-aligned investment choices. As more appealing options become available and reliable, more investors will choose these routes.

2. Start by investing where you want your money to be; it can be expensive to switch later.

Where you start is significant. Investing in securities (my way) means you’re usually taking a long-term approach. You’re not looking for a get-rich-quick win, and you’re hoping your assets will go up in value. That usually means it’s in your interest to stay with the same firm for many years — most investors do.

If you start with a conventional firm, and your securities are across the conventional asset class spectrum, it’s not so simple to painlessly change your setup. Sure, you can sell the shares you eventually realize you don’t want — but if you find you have unrealized capital gains, you’ll have significant tax to pay before you can reinvest in shares you might prefer to hold. It can be a big and expensive OUCH.

Which is why — from the start — having clarity about your values is ideal. Before issuing the “green-light go” to your broker, think about your values and what you don’t want your money supporting. The list can be quite long, and with some investment funds, not easy to customize.

In my case, I had initially identified that I didn’t want tobacco or alcohol. Then, as divesting from fossil fuels started to gain focus, I advised my firms: “No more fossil fuels, and ease out of any existing petroleum or coal.” Well, easier said than done. The trickle-down chain of fossil fuels is a complex web: from petroleum, to pipelines, transportation, and then petrochemicals, to the auto industry and plastics, the military, telecom and tech … and beyond.

Significantly, what about banks that underwrite this industry?

3. Banks are financing climate chaos.

We are waking up to an uncomfortable reality: Our Canadian banks are major enablers of fossil fuel exploration and expansion. As the magnitude of this reality has become more apparent, I’m uncomfortable knowing that I own shares in some banks that are involved in greenwashing. I understand we can’t quit petroleum cold turkey. I understand there are many necessary uses of fossil fuels that don’t yet have alternatives. But the science is clear: If we are to keep global warming and climate disruption to a livable minimum, no new fossil fuel projects can be developed. We have got to keep carbon in the ground.

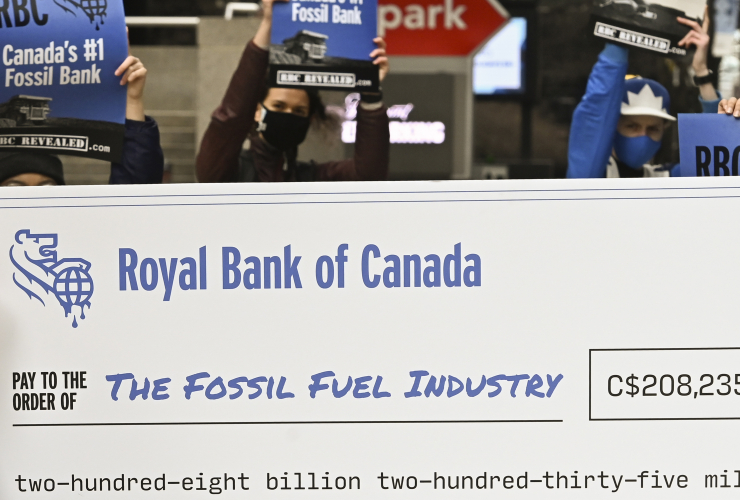

Some of our banks are a huge part of the problem. RBC is Canada’s top bank lender to fossil fuel companies, loaning at least $164 billion since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015 and purchasing at least $45 billion in shares. For global perspective, RBC is the fifth-highest bank financier of fossil fuels; Scotiabank is ninth, TD is 11th.

Turns out, I own some Canadian bank equities. Dismayed, I took my list of bank shares, and compared it to the list of Canadian banks that have significantly invested in petroleum since 2015. Next, I have tried to find out which of these banks are genuinely shifting toward sustainability. Turns out, RBC seems, so far, to be the least authentic about transitioning away from fossil fuel financing. Turns out, I have a lot of RBC shares, enough to prompt me to act — to write this piece, and to vote.

4. Try to be part of the solution, not the problem.

So, what do we do as shareholders when some banks are claiming to embrace sustainable practices and are aiming to be net-zero by 2050 (um, that’s 28 years to make a really big mess), but their carbon emissions are actually rising? There is some serious hypocrisy and environmentally destructive financing going on.

I have choices.

I can sell my shares, and either take a loss, or if they’ve gone up in value, pay taxes. Either way, sooner or later, there will be a reckoning.

Meanwhile, as a shareholder, I can exercise my agency and I will definitely vote in RBC’s AGM.

5. Vote when it matters!

Buried deep near the bottom of RBC’s lengthy AGM Management Proxy Circular, on Page 95, is a potentially pivotal shareholder proposal. This resolution seeks to prevent RBC from financing fossil fuel projects and ones that face significant Indigenous opposition under the bank's “sustainable finance” commitments.

To date, RBC is self-defining “sustainable finance.” Even though the bank is committed to sustainably lending $500 billion by 2025, without a clear and transparent definition of “sustainable finance,” much of this money could result in increased carbon emissions.

RBC board’s response to this proposal is vague, self-serving — and of course, it recommends shareholders vote AGAINST this proposal.

As a lawyer with some experience reading through dry material, I can tell you the board’s response to the specific concerns in this shareholder proposal sidesteps the concrete issues raised by the proposal’s authors. The board does not even mention fossil fuels or carbon in its response.

On face value, a reader skimming the board’s response might think, “Oh, that sounds good, they’re using eco-conscious words to make it appear like they’re doing good things.” Yes, the bank is taking some steps in some areas to diminish its carbon footprint, but in reality — thanks to skilled analysis by groups like Investors for Paris Compliance — it is clear RBC is greenwashing its strategies.

6. It’s time to cleanwash the greenwashing and align my money with my values.

I’ll be voting as a shareholder because I can. And then looking to divest; I will restructure my capital and hopefully sleep better at night.

Esther Chetner is a former litigation lawyer and has been on the advisory board of Canada’s National Observer for many years.

Updates and corrections

| Corrections policyThis piece has been updated to include biographical information about the writer.

Comments